Shawn Allen is a restless game developer. And a hungry one. Growing up on welfare will do that to you. But growing up on welfare isn’t enough to hold Shawn Allen back. In fact, soon, you might finally play one of his games.

Allen is 30 and when I ran into him several months ago at E3, he was standing on the upper tier of the Sony PlayStation booth, surveying a floor full of game publishers, retailers, developers and media at the biggest circus of new video games of the year. He was telling me that he felt a bit out of place.

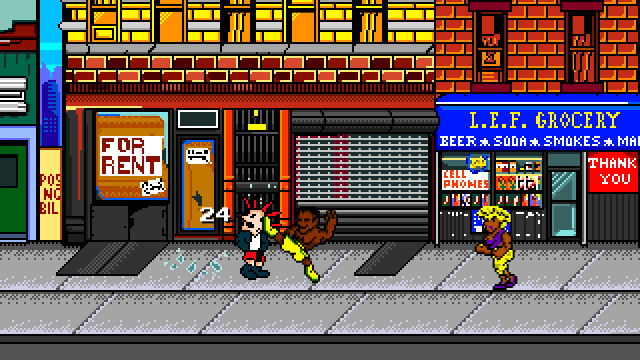

Here’s his path — a path that has led him to making Treachery in Beatdown City, a game that mixes old-school Streets of Rage side-scrolling brawling with a points-based, pause-and-plan combat system seen in games such as Fallout 3’s V.A.T.S. Check out this demonstration of the game to see why that’s a pretty good new twist:

Shawn Allen’s path starts in New York City’s Lower East Side. White mum. Black dad. Raised by his mum. Didn’t know his dad’s name until this year, he told me. Never even met the guy.

“I grew up in poverty,” he told me. His mum had worked as cab driver and as a repo person but eventually she stopped working entirely. They were on welfare until he was 14. She was diagnosed with clinical depression and they went on disability.

“We didn’t really have cash,” Allen recalled. Still, he ate fairly well. “My mum wanted to make sure she would shop on sale and buy the best at the least.”

He loved video games and remembered playing Super Mario Bros. on a friend’s black-and-white TV in the late 80s. He had a Tiger Electronics handheld, because you could pick one of those up for a dollar on the street. Eventually, he got a Game Boy, the old brick, “because my grandmother and my aunt sent money to my mum to buy me a game for Christmas.”

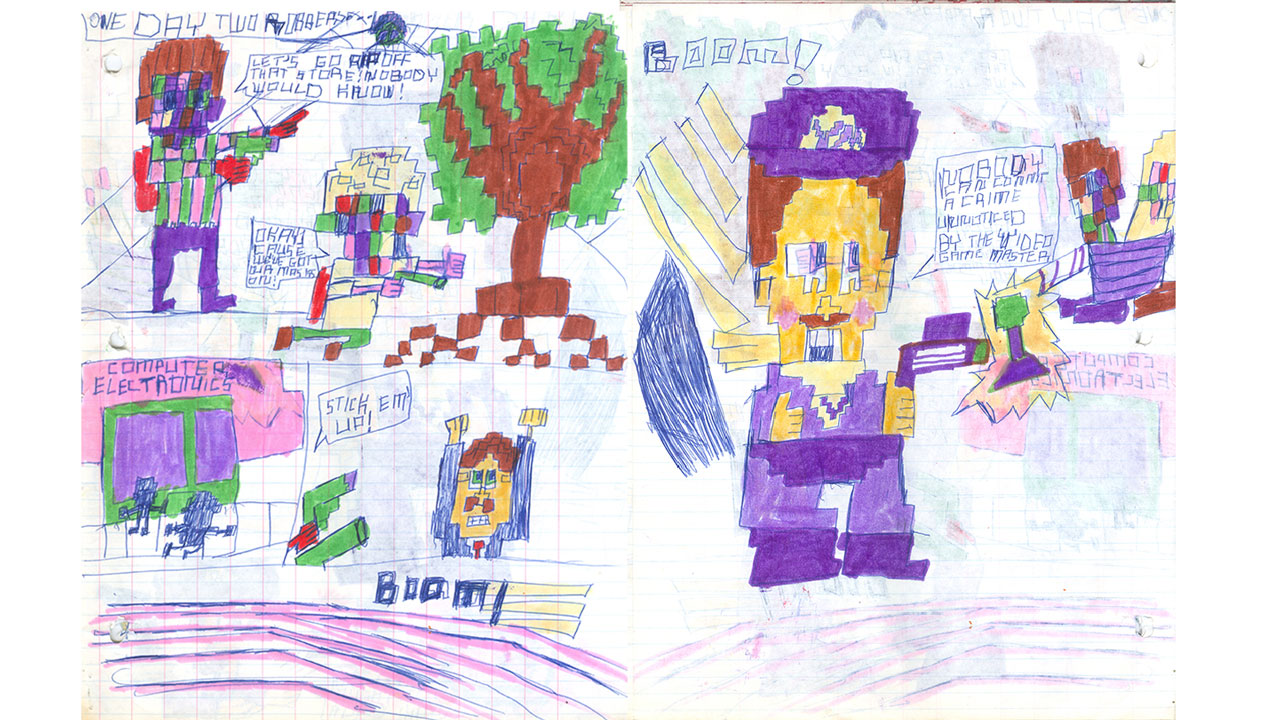

Here are some comic book pages he drew as a kid:

Allen fondly recalls getting a Nintendo 64, and he remembers working odd jobs to buy games. He was in high school and remembers going to a guy’s house in Williamsburg Brooklyn to haul bricks. He remembers needing just $US10 more to buy Mystical Ninja.

He can be a handful. I think he knows that. His life story is peppered with anecdotes of him getting on some people’s nerves. There were his instructors at the School of Visual Arts. “I had a lot of teachers saying, ‘Who do you think you are?”

There are people who, to this day, recognise him as a long-time employee of some downtown Manhattan shops, mainly a now-shuttered Electronics Boutique-turned-GameStop across the street from Rockstar Games. “I have people who walk up to me and say, ‘You were that guy at the game store. You kept it real.’ And there are other people who say, ‘That guy was an arsehole.’ I was very pragmatic. If you don’t want to buy the game, then don’t… People would want to know if a dollar game is any good…I’d be like, ‘It’s a dollar. Just try it.’”

Allen juggled SVA and his game store jobs until, about six years ago, he tried to cross the street and land a PR job at Rockstar. That almost worked. He got a job at Rockstar capturing live gameplay of in-development games — you know, like Grand Theft Auto IV — for trailers.

This jump, taken from a GTA IV trailer… he says he captured that:

“That’s something we spent a really long time working on,” he said. “I think we got it nice, but it had no explosion” The powers that be wanted an explosion. They set up the moment again and got it with an explosion. He wouldn’t say how. Tricks of the trade. But it was all in-game, he said. No make-things-explode-now button or anything.

Allen exited Rockstar in June 2012 and parlayed a connection he’d made with a Sony official at a PAX show to land a little bit of funding for Beatdown City. Well, first, he said, he collected unemployment and made a prototype in GameMaker and showed it to his Sony friend at an Indiecade event last year. Now he’s making the game with a friend of his, Manny Marcano, who lives in the projects. His buddy was working three jobs before Allen scored Sony funding. It’s been hand-to-mouth. “Manny, my programmer, actually ended up homeless for about a week because his grandmother died before she could add him to her lease and transfer over the apartment,” Allen told me. Allen’s wife has a full-time job. That helps. But, he says, there’s no safety net.

The game they’re making is on one level just a throwback. On another level, it’s the product of a life like Shawn Allen’s. “Each of the three [playable] characters are ethnic minorities who excel in life and are of varying levels of success,” he told me. “Lisa is one of the few (if not the only) Puerto Rican female protagonists in any video game… Enemies on the streets are based on people you can see on any given day in New York, painted with the cynicism of a New York native….There are also short vignettes that deal with a variety of topics that are all too familiar to me, like street harassment, what it’s like to be a minority in the city as well as gentrification and entitlement. It’s a bit of my frustration living in the city that I grew up in and love.”

Allen’s story isn’t meant to be a sob story. If anything, he’d like it to be inspirational. And he’d like it, in a way, to not be exceptional. When Allen looked out at the E3 floor he wasn’t really seeing any other developers like him. What he senses is that there aren’t that many developers with his background. It’s not just a race thing. It’s a class thing, too, all bundled up. It became the topic for a much-praised talk he gave at this year’s Indiecade in Culver City.

“The talk was essentially about how, even though we have this new independent games movement catching steam, it still hasn’t caught fire among black and latino communities,” he told me. “There are numerous reasons why that could be the case, but regardless of specifics, people who make games and find success as well as groups that facilitate the communities such as academia, conference planners and the fringe press/documentary makers who want to cover independent game creation shouldn’t accept the absence of black and latino people as something normal, but rather try to find ways to encourage participation from those communities. Indie games, as well as all games, would be better off with more cultural influence as has also been seen in other cultural forms.”

Allen and Mercado are working on finishing the first episode of Treachery in Beatdown City. It’s slated for release on PlayStation Mobile early next year.

Comments