There’s a scene in The Godfather that really resonates with me — not because I relate to it, but because I do not. It’s when Michael has dinner with Don Sollozzo, and they begin speaking to one another in Sicilian. There are no subtitles, and the first time I watched it, I was irritated. “What are they saying?” “What are they planning?”

But then I realised: I’m not supposed to know, because I’m not Sicilian. It is the film’s way of making its characters insular. It appeals to Sicilian audience members, and we non-Sicilians know this is a world we will never be a part of.

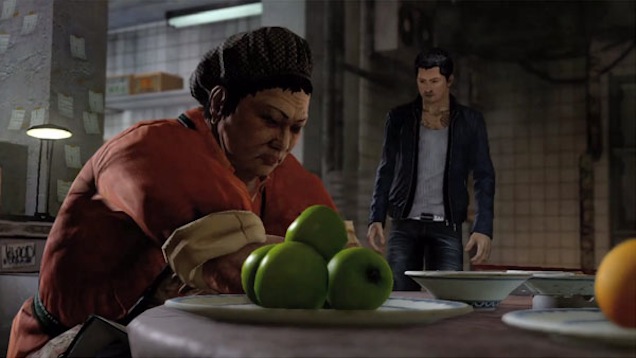

There’s a mission near the end of Sleeping Dogs — getting remastered for PS4, Xbox One and PC — that recalls a similar feeling. But this time, it’s because I understand. It’s the mission when you get your Triad Boss, Two Chin Tsao, to relapse on his heroin addiction. You do this by disrupting his feng shui, quite literally. You pick the lock on his front door, and once inside, you ruin his room aesthetic. You rotate his piano, and you steal his jade statue.

But there are also two odd, related events. You break four out of eight stand-up vases, leaving only four left. You set and freeze his clock to read 4:44. These are subtle nods to players of Chinese descent — ‘blink and you’ll miss it’ artifacts of my childhood — and then they are gone.

Four is a supremely unlucky number in Chinese culture.

I learned this early in childhood. It was the Chinese New Year, and my Mum and I were baking fa gao — little, pink ‘Prosperity’ cupcakes that we made only once a year. We packed them in small containers for visiting relatives, and my Mum told me that I could group them in pairs of sixes, but never in clusters of four. I asked why, and she explained to me that the number four in Cantonese — sì — was much too similar in sound to sǐ, which was the word for Death. It is one of several superstitions that my family holds onto from the old country, particularly around the Chinese New Year. Others include: oranges in every room, don’t wash your hair (that makes it hang low, like it would at a funeral), and always think happy thoughts, because whatever you think on New Year’s Day endures for the rest of the year.

It’s this little, cultural inside joke (and a dozen others) that makes Sleeping Dogs so impactful to Asian Americans such as myself. I identify closely with Wei Shen, the lead protagonist, who takes a tired archetype — that of the Asian American who is ‘trapped between two worlds’ — and reframes it in a way that is both authentic and relevant for a new generation of Asian American men.

Growing up, I was a novelty in my age range. My sister and I were second generation Chinese Americans — our parents were born in America. It was our grandparents — all four of them — who were born and raised in China. We lived in a town that was mostly white, and the few Asian kids in my town were all first generation — their parents were born in the old country. I was jook-sing — hollow bamboo. Neither as rich nor as substantial as a more ‘Chinese’ person could be.

It is with this cultural background that I began playing Sleeping Dogs. Several friends described it as ‘Grand Theft Auto IV in Hong Kong.’ But, immediately, Sleeping Dogs sets itself up more ambitiously.

Grand Theft Auto IV is the classic immigrant story — a foreign man with a rough upbringing comes to America in search of opportunity. Sleeping Dogs inverts these expectations. Like Niko, Wei escapes the restrictive confines of the old country by coming to America. But, unlike Niko, Wei makes the decision to ‘come back home’ — to Hong Kong, his old neighbourhood, and his old friends — and open up old wounds.

I was jook-sing — hollow bamboo. Neither as rich nor as substantial as a more ‘Chinese’ person could be.

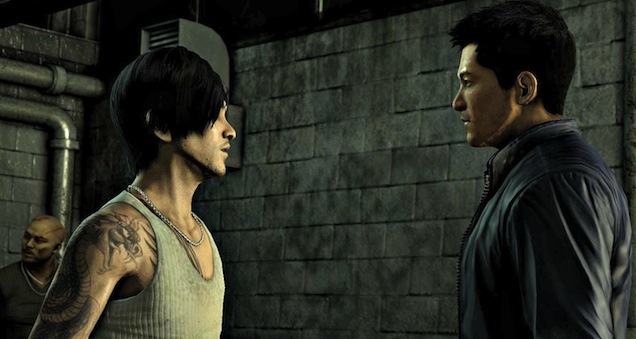

Wei experiences a variety of reactions to his ‘Asian American’ status. Jackie, his childhood friend, welcomes him back with open arms, but many other Triads see Wei as an outsider, and are hesitant to call him ‘brother.’ Wei’s shifu is disappointed by his presence — he worries that Wei should have stayed in America, and that by coming home, Wei has regressed. That’s my Mum’s mentality as well — my grandparents were farmers in rural China. The entire reason for leaving their homeland, after all, was because they wanted a better, more prosperous life.

Wei is not learning about Chinese culture, he’s relearning it and retracing a history he left behind long ago. Wei is not a Chinese male character — Wei is a Chinese American male character, and to me, that makes all the difference. I see myself represented, finally, with all the inherent contradictions and struggles in tact.

But unlike Wei, who lost his Chinese culture in America, I never had much to lose. My parents split up language duties — my mum would teach me English, and my father would teach me Cantonese. That didn’t work out the way they planned. I was in America, and so my parents emphasised that I learn English, really, really well, to the detriment of everything else. Thus, I grew up speaking and writing English exclusively — what little Cantonese I learned was gone by the time I was six. I kept my filial piety, and I still had little signifiers of Chinese culture — three bows at the cemetery, never group things in fours — to hold onto.

Today, I am an English teacher and writer, and so I don’t regret my upbringing. But this doesn’t prevent other people from finding fault in my monolingualism. Most Asians and non-Asians project a mixture of condescension and pity — proclaiming that I have been deprived of some crucial, cultural component. That I am not a ‘real’ Asian — that I am more ‘white’ than anything else.

These early insecurities made me sensitive to the way language is used in Sleeping Dogs. Older characters, such as Mrs. Chu, speak exclusively in Cantonese, as my grandparents did. Many of the younger characters, like Jackie, use English mostly, but punctuate their dialogue with Chinese phrases — for impact and emphasis, just like my Dad. And then there is Wei, who speaks in English almost exclusively. Even when Mrs. Chu speaks to him in Cantonese, he responds in English. You get the impression, from their facial language and awkward pauses, that they barely understand each other.

It reminded me of my relationship to my nǎi nǎi, who resented our non-Chinese upbringing. She knew a limited amount of English, but she refused to use it. Instead, we carried on through bizarre pantomime. When I was on the phone, she would speak to me in Cantonese, and I, not understanding a word of it, would enunciate those syllables to my Dad. My Dad would then enunciate syllables to say back, and I would repeat them back to my nǎi nǎi. I was a vessel for conversations, but I didn’t understand any of them — not a word.

My nǎi nǎi died when I was six, and there was never an opportunity to understand more. We didn’t really understand one another either, but there was still a connection there, and an effort (however fruitless) to communicate on her terms. And for me and her, that had to be enough.

Sleeping Dogs shines when its characters relate and communicate, however awkwardly, across cultural boundaries. And as such, it’s one of the first video games, in my memory, that gives an Asian American male protagonist an active love life. Not only that — it is a love life full of complexity, and fraught with interracial implications. In Sleeping Dogs, the first woman Wei dates is Amanda, a blonde, blue-eyed, wide-eyed white woman. I’ve become used to seeing Asian men in asexual or feminized roles in American culture — from Charlie Chan to Mr. Yunioshi to Long Duk Dong to William Hung to every tech nerd supporting character in Hollywood. I was surprised — shocked, even — to see an Asian American male character who was romantically involved with any woman, let alone a white woman, in a mainstream production. Typically, Asian men are paired with Asian women. It’s the more socially ‘acceptable’ option, and mainstream representations of Asian men in relationships don’t usually involve an interracial pairing. Sleeping Dogs represents a more open-minded idea of romantic interests, and plays on people’s preconceptions.

The game also represents problematic attitudes towards interracial relationships. Wei has an internalized, stated preference for blonde, white women; in America, dating a white woman is seen as a status symbol by many men of colour. It’s a distasteful objectification and a signifier of dominance — that sleeping with The Man’s woman is to claim alpha status over him.

But after their hookup, Wei does a little digging, and realises that Amanda is a bit of a fraud — she fabricated her entire academic background, and she also appears to have a racial fetish, dating Chinese men numerously and exclusively. It reminds me of my white roommate in college; he attended ‘Asian’ parties and took ‘Asian’ classes in order to meet Asian women, because they were so ‘feminine and exotic.’ Amanda has agency, and she is an interesting inversion of the whole ‘Bro with Yellow Fever’ thing. Wei thought he was the alpha male, but ironically, he was the objectified one.

For the rest of the game, Wei dates Asian women (with the exception of Ilyana, and even she is foreign-born). The dates have an element of cultural show and tell — each of the Asian women signify an aspect of Hong Kong youth culture, and they expose Wei to what he’s been missing from an adolescence spent abroad. There’s Tiffany Kim: a karaoke enthusiast. There’s Not Ping: a tech/hacker nerd. And there’s Sandra: a groupie for Hong Kong’s growing car culture.

Wei’s fumbling experiences remind me of my first karaoke date. I had never dated an Asian woman before, and the first Asian woman I dated was from mainland China. She had a thick accent, she wore clashing, brightly coloured clothes, and she clapped when she was happy; to me, these were decidedly ‘Asian’ mannerisms, and had I been younger, they would have embarrassed me. I remember sitting down in a private karaoke room with her, and searching through the machine. We were in Chinatown, and 99% of the songs were Hong Kong pop. Any American song was covered by Asian artists, with sappy ballad instrumentations. For my entire life, I had viewed Asian culture through an American lens. And now, for the first time, I was viewing American culture through an Asian lens.

For my entire life, I had viewed Asian culture through an American lens. And now, for the first time, I was viewing American culture through an Asian lens.

My next girlfriend was a woman from Hong Kong, and she found my ‘American’ mannerisms odd and endearing — Diet Coke instead of tea, forks instead of chopsticks. She exposed me to Hong Kong pop music, to bubble tea, and to Asian cinema. As with Wei Shen, there was a sense of discovery in these relationships — exposure to a youth culture I had ignored, partly due to my lack of exposure, but also due to my own insecurities — a defensive posture — that my American culture was superior to the Chinese culture where I was unwelcomed.

Wei also endures this push and pull between two cultures — the Chinese Triad culture, with its familial brotherhood and tribal loyalties, and the American Cop culture, with its objective principles and loyalty to country. Ultimately, Wei manages to split the difference — he stands by the Triads who treated him with familial warmth and care (while killing those Triads who betrayed established tradition), and he upholds American, national principles (while flushing out the most impersonal, corrupt elements of them). Wei realises that he does not have to choose one side or the other. Rather, he can compromise on both, and embrace both as parts of his Asian American identity.

I too have found ways to make peace with my cultural identity, or lack thereof. I still can’t speak Cantonese fluently, but I do know my way around a restaurant menu. I didn’t marry a Chinese American woman, but I did marry a Filipino American woman, who is as Americanized as me. I teach college level English to high schoolers. I love Hong Kong cinema, but I still hate karaoke. And I’m proud, for the first time in my life, to claim myself as an Asian American, in the truest, most conflicted sense of that phrase.

I’m thankful that Sleeping Dogs is being re-released (with a sequel on the way). More people can see the confusing, awkward experience of growing up American, only to rediscover one’s cultural, ancestral side late in life. It’s both embarrassing and exciting — to have missed so much, and to now have so much exploring and reconciling to do.

Kevin is an AP English Language teacher and freelance writer from Queens, NY. His focus is on video games, American pop culture and Asian American issues. He wrote a weekly column for Complex called “Throwback Thursdays”, which spotlighted video games and trends from previous console generations. Kevin has also been published in VIBE, Salon, PopMatters and Racialicious, and he will soon be published in Joystiq. You can email him at kevinjameswong@gmail.com.

Comments

5 responses to “What Sleeping Dogs Gets So Right About Being An Asian-American”

That was a really interesting read. I hope more games follow sleeping Dog’s example and branch out a bit more both in location and the nature of their main character. Wei Shen was a really fun and interesting character to play as and honestly probably my favorite main character of the open-world GTA-style games.

Agreed. I found SD’s environment to be really refresheing, especially the mix of Cantonese epithets. Great article.

Quite excited to play the newer version, I put 20 hours into the last one and never finished it (and 2 hours into the Xbox 360 version before I couldn’t stomach the visuals anymore).

Great article. SD was a special game not only in its design but in its respect of all cultures. It presented barely any stereotypes and was a damn good time. Look forward to reading more from you.

Good read.

I always thought that labelling Sleeping Dogs as “GTA in Hong Kong” was such a misnomer and misses the point of the game a bit…

If anything a more apt comparison would be one of the HK triad movies like a video game adaptation of “Infernal Affairs” or the like. HK crime/triad films have such a completely different feel to them when compared to your standard “wiseguy/mafia” films.