Metro: Last Light is relentlessly linear, right up until it isn’t. It gives you a trusty ally to follow, right up until he betrays you. As the game pulls the rug out from under you, leaving you completely alone, it becomes clear: all of this was by design.

Last Light begins shortly after the events of 2033, where you, a ranger named Artyom, launched some nuclear missiles into the home of the Dark Ones, psychic mutants that were believed to be planning an attack on humanity. A Dark One has now appeared near your home base, and you are tasked with hunting it. Unfortunately, in the process, you are captured by Nazis and brought to their station. They have also captured a Soviet, Pavel, who helps you escape.

One of the worst sins modern shooters commit is their insistence on ‘walk and talk’ segments, where the player speed is faster than the person doing the walking and talking and the player often has to stand still and wait for the walkertalker to open the door for them. This extreme handholding is almost always dull and boring; what’s being said is never really important, and making the player wait around while a character goes through the motions is rarely engaging or meaningful game design. Last Light has many of these sections.

In fact, the game’s first several hours are incredibly linear, with the player following characters, mostly Pavel, being told this or that thing while waiting for the characters to open doors or interact with objects. Sneak up to a room, wait for Pavel to say it’s ok to move, move, wait for him to try — and fail — to open a vent, wait for him to realise he can’t and try to climb a ladder, wait for him to climb the ladder, follow him around a bend, wait for him to tell you to kill a Nazi, follow a two foot-wide path for the next five minutes, killing Nazis occasionally… it’s something that would feel dull in any other game.

Metro, at least, slathers on the atmosphere so thick that it’s hard not to feel like you’re really there, sneaking through a Nazi base with Pavel at your side, pausing in the shadows as you wait for a massive fan to provide cover, letting you sneak through. The path is narrow because you’re making your way through a prison built into the walls of a massive ventilation shaft; the narrow paths emphasise the precarious positioning of the cages.

Everything makes sense, but the game’s doing something else: it’s encouraging you to depend on Pavel. It’s Pavel who breaks you out of prison, and later, it’s you who breaks him out when he’s been recaptured. One of the best moments of Last Light’s first few hours involves a brief trek above ground. You and Pavel enter a wrecked airliner, but the presence of the dead is so strong that you begin to relive the memories of the people who lived there.

You manage to break free, but Pavel is lost to the memories; he removes his mask, a death sentence above ground, because he ‘can’t breathe’ as he relives the memories of ghosts who asphyxiated from the smoke as their airliner burned. You snap him out of it, and the two of you quickly rush out of the plane.

These haunted places add a great deal of power to Last Light’s atmosphere. I’ve played plenty of games with ghosts in them, but most ghosts are individual, malicious beings. Last Light’s ghosts are more like whirlpools of bad memories. Walk through trench where one of the bombs fell, for instance, and a thousand dead arms reach out, hoping to pull you in, to make you one of them. It’s as if the horror of what happened in some of these places was so powerful that it left a psychic scar with an insatiable hunger.

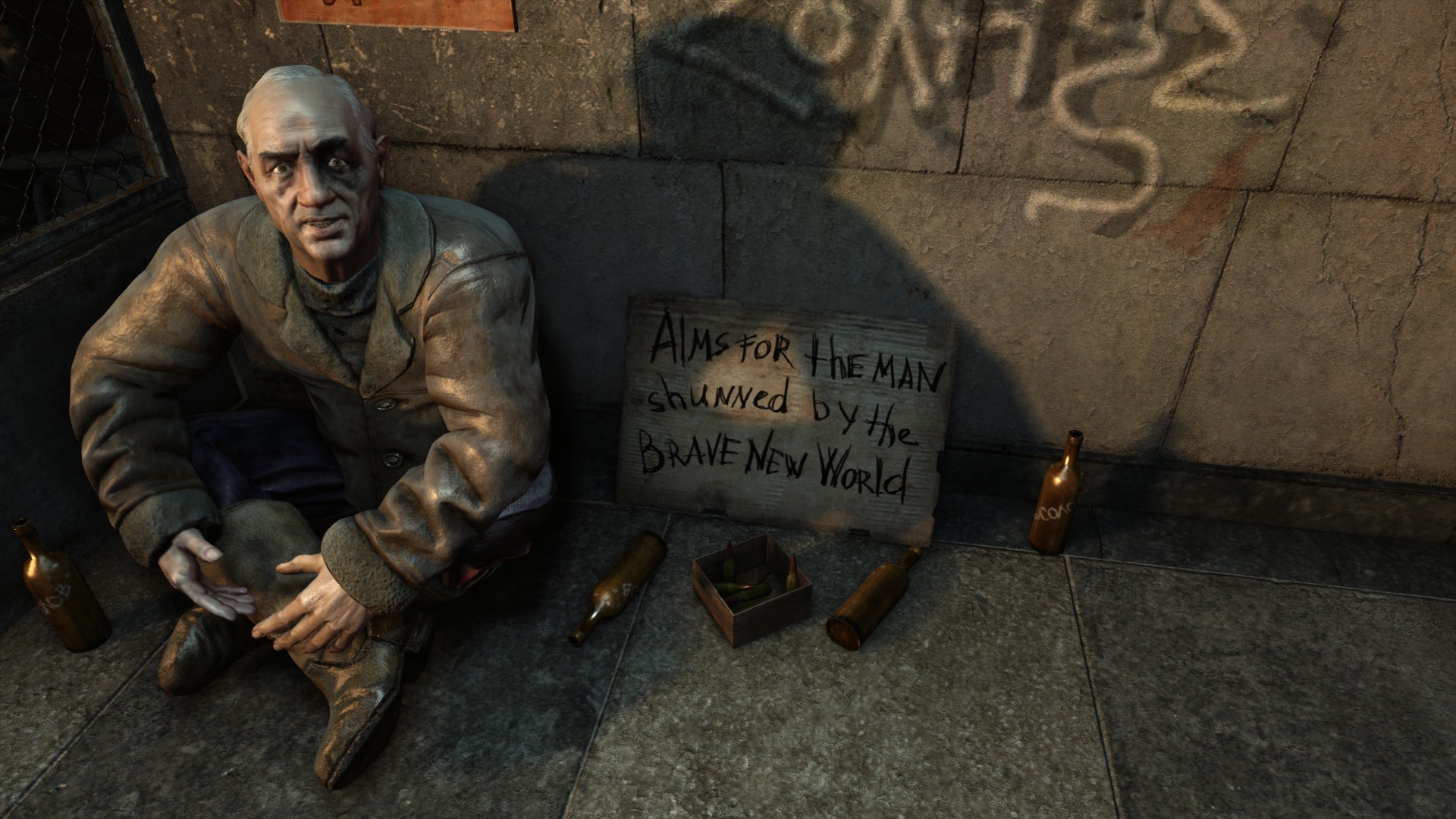

If you talk to the folks who live in the Metro, though, you’ll find those who know how to deal with these places. There’s the sense that some places can be bargained with, granting safe passage. Mechanically, this usually means doing exactly what you’re told, keeping Last Light relentlessly linear.

Up until the theatre, Pavel has been a great companion. He doesn’t believe the way you do, and he feels the need to justify himself and explain that the Communists aren’t all bad guys. When you need saving, he’s there for you, and you’ve done the same for him. His verbal tics, the “tak-tak-tak-tak” he says when he’s trying to come to a quick decision, have become endearing.

Then he betrays you.

Your guide, the person who’s done most of the game’s handholding up to this point, suddenly becomes your enemy. You saved his life countless times, and he repays that by sending you to the torturers. You’re alone now, but you’ve also got a white-hot motive: hunt Pavel down, stop him from helping the Communists, and get revenge.

This is where Metro: Last Light flips its own script. Without Pavel, you’re alone. The game introduces this sense of creeping tension: it’s one thing to explore the Metro with a guide, but when you’re off on your own, the tension starts to climb higher than it did before. You’re listening to monsters crawl around, waiting to strike. Luckily, the first few areas without Pavel are fairly easy to explore. You travel through a linear Metro tunnel, get in a few firefights, and eventually end up in a partially-flooded station called Venice. Shortly after that, you’re on your own. One of Venice’s inhabitants tells you where the nearest ranger station is, tells you that you’ll want to find some fuel, and then leaves you to it.

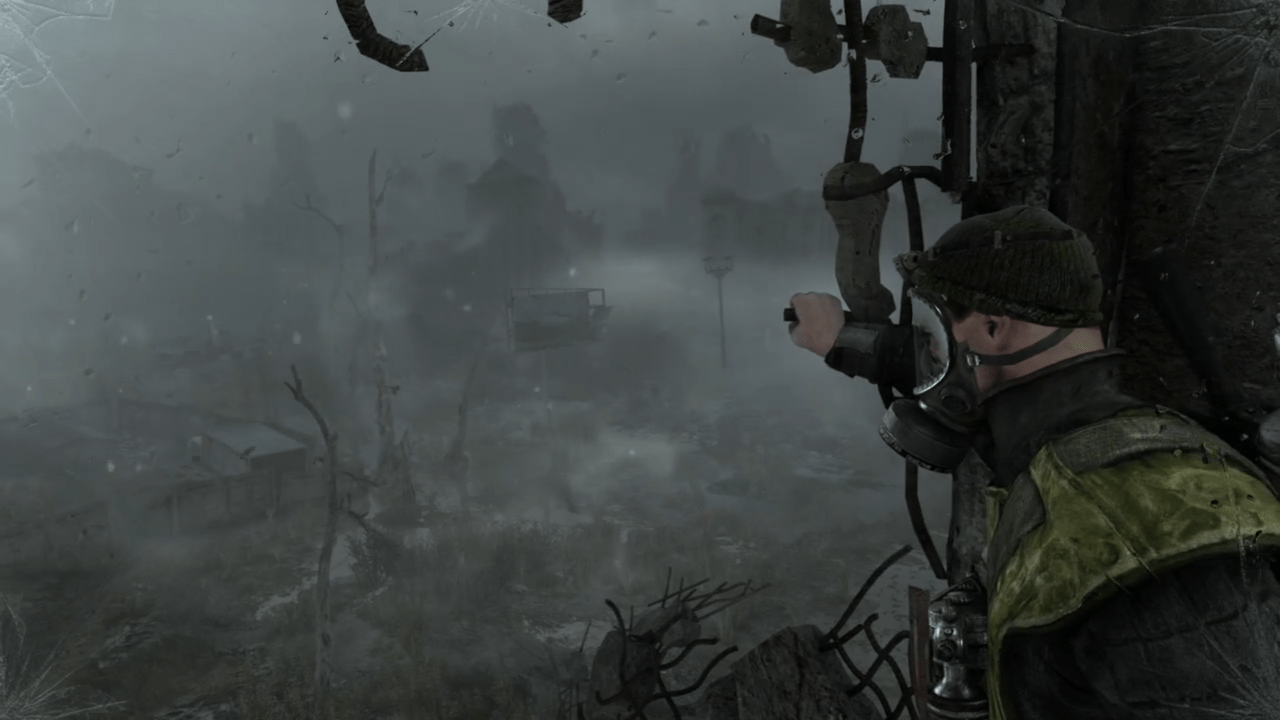

Up to this point, you’ve never been alone above ground. Below, sure, but it was always easy to figure out what to do: follow the linear tunnels, occasionally shoot some guys, keep moving. Nothing to it. Above ground, everything changes.

One of the most notable aspects of the Metro games are the gas masks: spend time above ground, and you’ll want to have plenty of air filters. Every few minutes, you’ll have to replace a filter to keep breathing, or you’ll slowly choke to death. It adds tension to the levels; you’re always running around with one eye on your filter and another on the world around you, hoping you find more filters.

Last Light isn’t content to leave it at that. It introduces a new monster type, the amphibian, which slithers towards its foes while trying to protect its weak points with its armoured limbs. The amphibians stalk you throughout the level, which is stressful, but it gets worse when an even bigger, practically invincible amphibian shows up looking for a snack.

The openness of the above-ground levels is disorientating. All you can do is scramble around the level, searching for gas and evading the mutants that come looking for you. At one point, you may get into a tussle with a demon, one of the largest monsters in the game, which swoops out of the sky on its bat-like wings and attempts to fly off with you.

If you manage to find the right fuel can, you have to fuel a generator that pulls a little ferry toward you. The big amphibian attacks, enraged by the generator, and it’s only frightened off when the demon that’s been eying you swoops in. The two fight to a standstill and flee, leaving you to board the ferry and cross the bog.

By now, it’s dark. More mutants, like the four-limbed, wide-eyed creatures known as watchmen, have come out to play. A nearby building looks inviting, but it’s full of boobytraps that, at night, are particularly hard to spot, especially if you’re trying to keep your flashlight off. There’s a radio playing — a friendly character calls out to you, saying you should make your way to the church, which, at night, is hard to spot.

Setting out, you wind your way through the marshes, uncertain of where to go. Whenever mutants spot you, the onslaught is intense.

Your loneliness is at its harshest here in the dark, with mutants prowling and no clear sense of where to go. You eventually spot a makeshift path and arrive at the church, but just as you approach the church, you’re knocked to the side and land in a makeshift arena. The giant amphibian mutant has been following you, and it’s ready for a snack.

The ensuing firefight is chaotic and intense, with rangers firing from the church and you running madly around, kiting the mutant and doing occasional damage. It’s a moment of gleeful anxiety as you dash around, just a hair’s breadth from safety, soldiers shouting and monsters roaring. When the monster finally dies, you enter the church, safe at last.

…until the Communists attack. Wreckage from an explosion knocks you out cold. When you wake, you are alone once again, with your only avenue of escape leading through the crypts beneath the church. This level is scary not because you’re in a crypt, but because of the ominous, thundering roar of a new monster that stalks you throughout the level. It stomps around with such strength that it shakes the entire level, and its roar is so loud that it even frightens other mutants.

Eventually, you come face to face with the Nosalis Rhino, an armoured monster that can’t simply be shot to death. It’s a challenging encounter to complete, and when you’re done, a torrent of water washes over you, dragging you down into the tunnels below. When you wake, you’re back in the metro, ready to continue.

It’s hard to do linearity right, but Metro uses it and the dependency it creates to enhance tension. By creating player dependency on various NPCs and then taking those NPCs away, Last Light conjures a crushing loneliness that I’ve never experienced in other horror games. I’ve been frightened, startled, and panicked, but never once have I felt as desperately alone as I have in Last Light, and it’s all thanks to the game’s first few hours of linearity.

I’m a sucker for intense emotions in video games. Last Light‘s big on negative emotions like tension and horror, and I think that’s what makes it such a memorable game. It’s hard to do linearity right, but 4A did a fantastic job of making Last Light‘s linearity feel justified and logical. I’ve played plenty of games that try to make the player feel things by resorting to tired tropes and simple tricks, but Last Light goes all out. It fosters a relationship, then takes it away. It creates a friend, then turns him into a foe with a betrayal that feels completely right for the character, instead of being a forced twist.

Near the game’s end, the player is given a choice:doom Pavel to death, or forgive him. It’s one of the more obvious choices in the game, but it’s also one of the hardest. Pavel makes it clear that he thinks of you as a friend; it’s just that he’s more loyal to the Communists, who he believes have the power to save everyone in the Metro. Without having experienced those first few chapters, without having been so dependent on Pavel, I don’t think my decision would have been difficult., Because of my first few hours with him, I dreaded having to choose. Metro: Last Light played me like a fiddle from its very first act, and elevated itself in the process.

Comments

11 responses to “How Metro: Last Light Flipped The Script On Players ”

But what did you choose?!

Tried playing one of the Metros, gave up very early due to this exact linearity. I get that a lot of games are made better by holding your hand, but this reminded me of a Call Of Duty game that respected my intelligence even less. Even if that does change later on, the fact that there was little hint of that in the opening hours seems like a really poor choice.

Put your best foot forward, or at least give a reasonable indication that there’s something more to what we’re seeing.

The thing is, the game is linear because it’s telling a story, sometimes being linear is ok. It’s not about holding your hand, it’s about experiencing the game they made for you in the scripted way they made it. Why does it matter, there are plenty of other games that give you more open experience and choice, but this isn’t one and it’s not trying to be one. I just don’t think that is a valid critique for this game.

It won’t exactly encourage replayability but I don’t think that was their intention. I bought both Metro games and finished them once, never replayed, thought they were great. I personally hate multiplayer in games anyway unless it’s co-op, so I literally buy a game for the story and then shelve it after that. I would never buy CoD or similar because the story is so short and not worth my dollars, plus I would never play the multiplayer. (Spent years in high school playing Counter Strike – totally over it).

Really looking forward to a sequel for Metro, but will be busy with Fallout 4 until then.

Yeah I love linearity. If a game is open world these days, it’s actually a negative for me. This obsession with “freedom” completely dilutes characterisation, plot development and even the engagement of gameplay.

But you look at a game like Last Of Us that’s linear as hell, there’s something about that game that pulls you in from the get go. Better acting and plot perhaps? I don’t know. I definitely remember hating the fact that there was all these characters speaking English in Russian accents to other Russians instead of just straight Russian when I started the game. Small thing, but it just pissed me off. Pretty sure you can actually change that in the options but the damage was done.

Light spoilers if you haven’t played Last Of Us here:

Maybe it was the sense that The Last Of Us was really going somewhere with its plot. Perhaps it was the inclusion of Ellie but not Tess in the marketing material that made you wonder how the opening situation would change. Maybe it was that opening sequence with his daughter. Super linear, but amazing and arresting.I think what it boils down to is feeling like your actions matter. In games like Call of Duty and this, I feel like every bullet I fired was as the result of a directive, rather than a choice. In games like The Last Of Us, there’s a very linear story and environmental progression, but when it comes down to making choices as a player, they give you an area, a group of enemies, limited resources, and an exit point, and say “deal with it”.

Fair enough, I did find myself being scarce with my bullets in Metro though as quite a lot of the monsters weren’t worth fighting due to your limited ammo and resources. I really wanted to play Last of Us. I bought it for PS3 early on and lent it to my bro on day one as I didn’t have a chance to play it, then got it back a while later and never ended up playing it. Another game in my collection that sits there that I never played :(. From all reports it’s a great game though.

Also with open world games like fallout 4, you could simply focus on the main quest from start to finish with all of the side quests treated purely as a bit of a choice or change of pace if you get bored.

Nah. See, this guy had a different perspective and it worked out perfectly in term of design, you might have a different attention span but that doesn’t make this a flaw, it doesn’t diminish it’s relevance to narrative, it just means you need to be i pressed at the start. Many people in the film industry have come to this conclusion as well, however this has resulted in almost blueprint scripts where important events are divided up amongst the narrative by incrementa of time. Subsequently, this has led to a homogenisation of stories, where every intro happens at the same pace, every story has the same structure because people need to be wowed at the start instead of following the journey, not only disliking creative structure but making excuses why something doesn’t work in an attempt to gain legitimacy before ever holistically considering a different perspective. People are more enamoured with their perspective being the prevailing argument rather than accepting different stories with different approaches. Dislike the story all you want, just don’t pretend techniques that work for many don’t actually work because you aren’t willing to consider the majority of narrative conventions explored in the article.

Yeah, just arguing my perspective, not arguing that it’s the prevailing argument. I know a lot of people liked the game. I’m definitely not a fan of the homogenisation of stories in any medium as well. I’d argue that the whole “follow the leader” mentality has been entirely played out by Call Of Duty / Battlefield though, so Metro’s not exactly blazing the trail here. Bioshock 1 had a similar betrayal storyline based on the recap in this article too.

I would argue my attention span is better than most people, I love when games do something different and the last thing I want is endless action, but there are objective truths about how much you expect the audience to endure before you get to the payoff. A masterful storyteller could definitely tease out a climax like this game seems to have for an extended period of time, but i’d argue the video games industry doesn’t have any of those just yet.

I’m not trying to invalidate anyone’s perspective here, just give my own and hope for an engaging discussion.

Great article. Have to say both Metro’s are my favourite FPS’s. I played the first one and loved it so much, I went and bought the book, which is awesome too. It had some annoying glitches like getting stuck on invisible rocks but the atmosphere was so intense and I never felt the immersion was broken. I had no problem with the linearity and I guess that is because I love a good story.

I would make a bet that people who don’t mind linear games spent a fair bit of time reading books while those who hate linear games and want open world games all the time probably read books less.

Like a damn fiddle.

Read the first book, then play both of these games in order. Simply fantastic fan fare. Last Light is the better game as the visuals enable you to be sucked in a lot more.

Seriously though, read Metro 2033 and play these in the dark………remembering they cost like $20 or something stupid.

it’s still linear and shit.