The first time that Cyberdreams producer David Mullich showed author Harlan Ellison a page of the dialogue he’d written for the 1995 game based on his short story “I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream,” Ellison asked, “Who wrote this shit?”

When Mullich replied that he had, Ellison got visibly embarrassed and apologised. “No, that’s all right,” Mullich replied. “It is shit compared to your writing. So, take it and make it better.”

Harlan Ellison, who passed away on June 28, was a grand master of science fiction who published over 1,700 works and won multiple awards from the Hugo to the Edgar Allan Poe. “I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream” is one of the ten most reprinted stories in the English language.

He also was known for being a crank and had no love for video games, calling them “time wasters.” When he was approached by Cyberdreams about optioning the story for a game adaptation, he was sceptical.

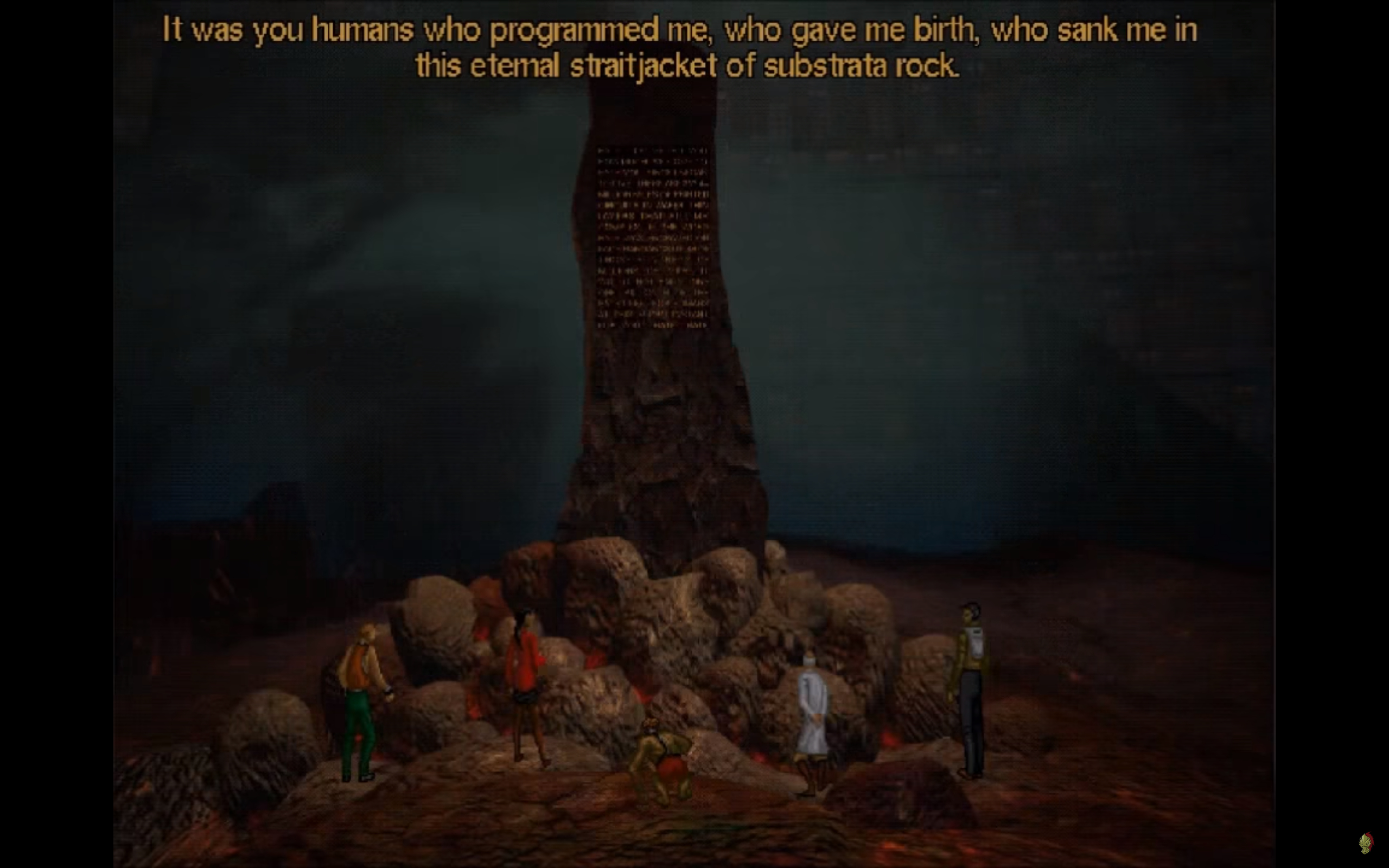

Still, the financials worked and the opportunity seemed promising, so he agreed. On the surface, it seemed like a strange choice for a game, as the short story focuses on the psychological terror of five humans held captive by a hateful and murderous super computer called AM.

But the team at Cyberdreams, led by David Mullich, developed one of the best psychological horror point-and-click adventures games for the PC, a title which has made Kotaku’s Complete Directory of the Classic PC Games You Must Play and Nine Adventure Games We Wish Had Sequels.

From Prisoner To Cyberdreams

Mullich’s interest in science fiction was what led him into the game industry. As a child, his creative energy drew him to a variety of outlets that included “drawing illustrations, writing short stories, filming Super 8 movies, performing neighbourhood magic shows, acting in school plays, and making my own board game.”

Because of his diverse interests, he had a difficult time deciding on a major when he entered the California State University of Northridge. But his love for science fiction convinced him to take a computer science class where, using a shared printer in the computer lab, he started writing a Star Trek game.

It was there he “realised that a computer could be used as a storytelling medium, just as could a typewriter, easel or movie camera. I ran over to the Administration building and changed my major from Undecided to Computer Science.”

At one point, one of his computer programming professors caught Mullich using the university computer to create visual art and even generate poetry. When his professor called him into the office, Mullich believed he was in trouble.

Instead, he was offered a job working as a clerk in a computer store that Sprouse owned with a couple of the other professors of the university’s’s Computer Science Department.

His initial job at the small retail shop near campus was to write a database program to sell to the store’s customers. After completing that task, he moved onto to fulfilling orders from a software catalogue from a publisher called Rainbow Computing.

“Back then there wasn’t much in the way of professionally-written software or software publishers for the Apple II, and so most people bought computers as hobbyists and wrote their own programs for storing recipes, balancing the checkbook, or playing games,” he said.

“Many of our customers would bring their programs to Rainbow Computing to sell in Ziploc bags with photocopied documentation.”

In between writing programs, he worked on the sales floor, which would lead him to a pivotal encounter with Sherwin Steffin, who had had started a publishing company called Edu-Ware Services out of his apartment. After talking, Steffin recruited Mullich to write some games for him to publish.

Over the next year, Mullich wrote three games for Edu-Ware: a text-based science fiction role-playing game called Space II; an oil crisis economic simulation called Windfall; and a television network programming game called Network.

“They were small but steady sellers and received good reviews,” he said, “and when I graduated from college, Sherwin hired me full-time as a programmer.”

His first projects at Edu-Ware as a full-timer were programming educational tutorials to teach maths. But Mullich was obsessed with a television program called The Prisoner, a 17-episode British series from the 1960s in which a former British secret agent is imprisoned in a strange village and kept there until he’ll reveal why he abruptly quit the service.

Psychological horror, memorably strange characters, and Kafkaesque scenarios abound in this fascinating show that broke all genre molds. Mullich was able to convince Sherwin to allow him write a game based on this “surreal and metaphorical spy series about maintaining one’s individuality.” He worked on the Prisoner game for about six weeks, “designing and programming it in sort of a creative frenzy.”

Fortunately, it turned out to be both a critical hit and a best seller. It also paved the way for his opportunity to work at Cyberdreams with Harlan Ellison.

Screaming Without Screaming

Mullich had long been a fan of Ellison’s work. The Hugo-award winning short story from the grand master of science fiction, “I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream,” was one of Mullich’s favourites, as well as the Star Trek episode Ellis wrote, “The City On The Edge Of Forever,” with its mix of ethical dilemmas, time travel, and Nazis.

Mullich said that by the time he came to work at Cyberdreams as producer of the I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream video game, the original game designer David Sears had “departed from the project.” But Sears had made several key contributions to the design.

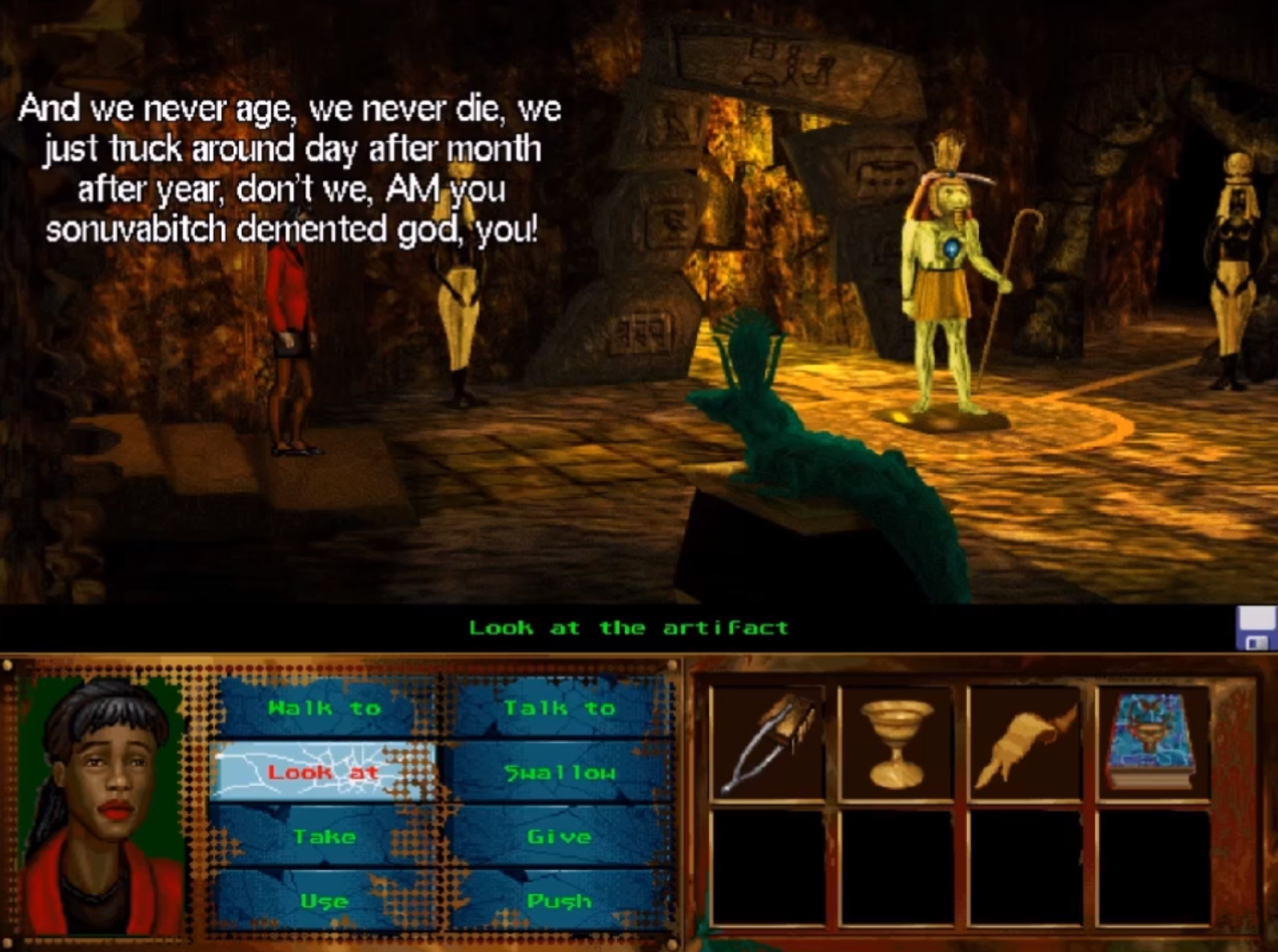

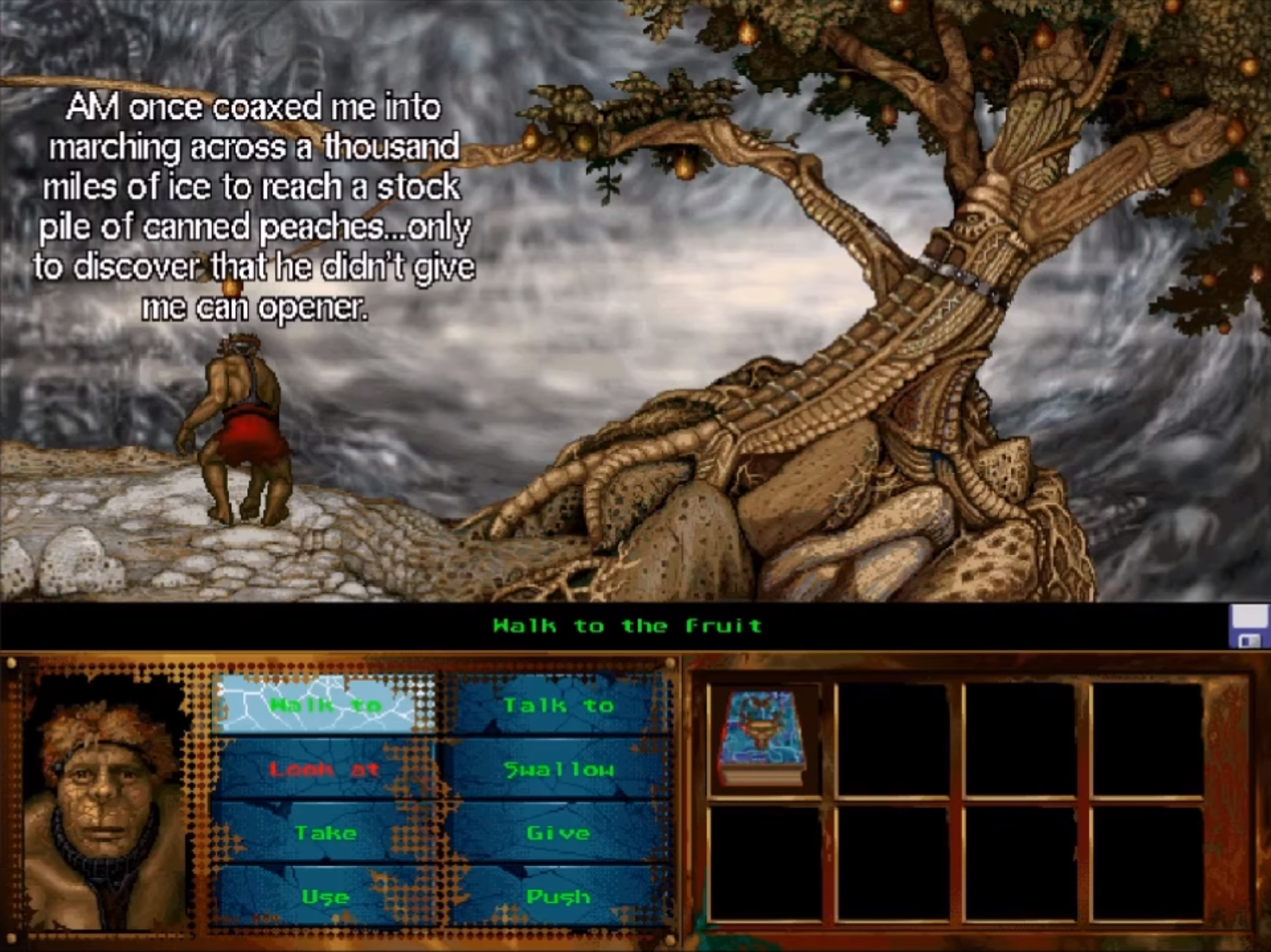

In the short story, the supercomputer AM subjects the final five humans to a perpetual series of cruel punishments: “Hot, cold, hail, lava, boils or locusts–it never mattered: the machine masturbated and we had to take it or die.”

But their characters and their personal histories weren’t explored in-depth. Sears asked the question that led to the main breakthrough of the game: “Why did AM choose these five people to keep alive and torture after wiping out the rest of humanity?”

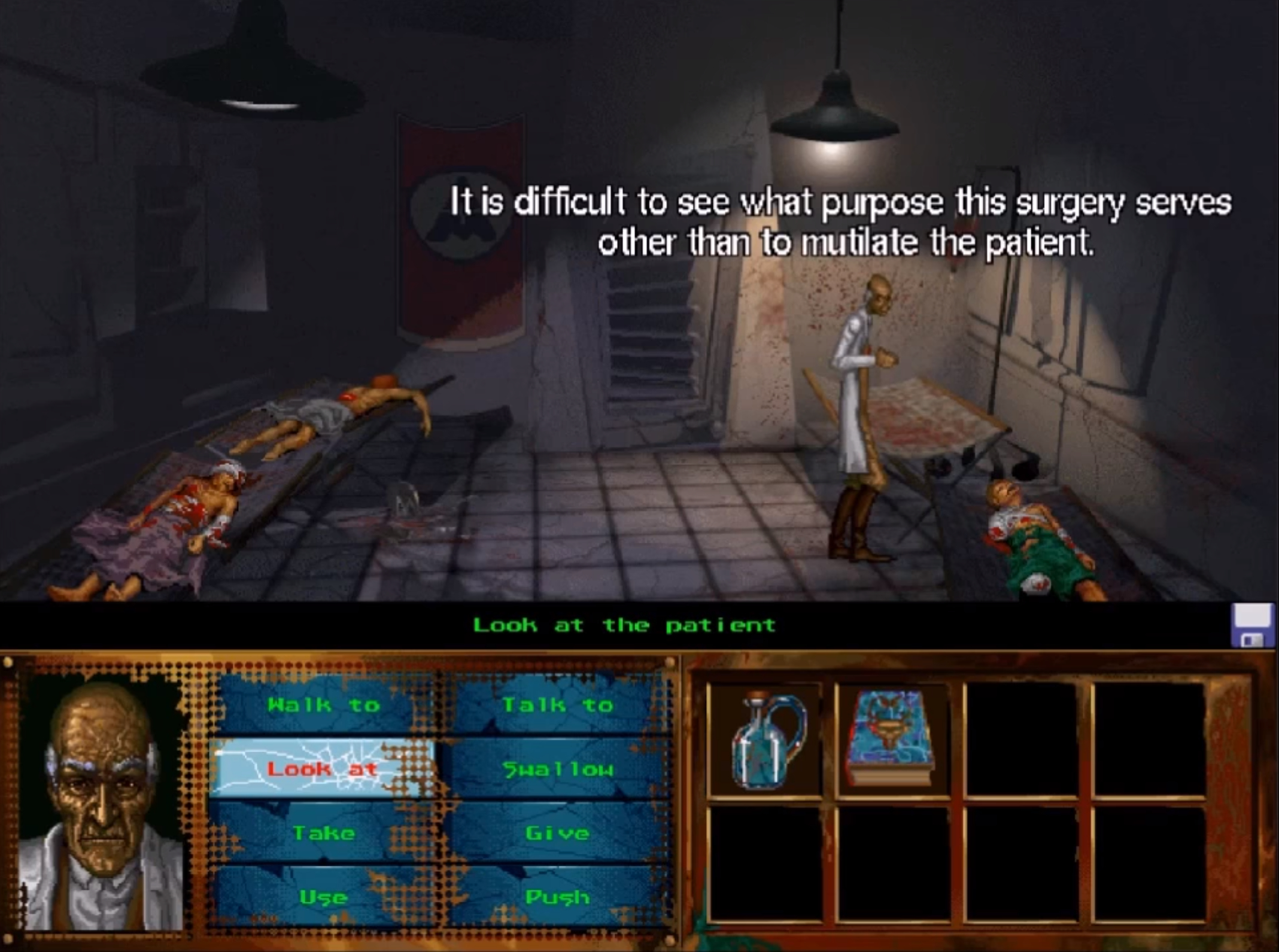

This question inspired Sears and Ellison to write longer backstories for each of the characters. The game would revolve around their individual journeys. As Mullich explained, they would each come “to grips with their guilt over something terrible from their past: Gorrister committing his wife to a mental institution, Benny killed members of his own military unit, Ellen being a victim of sexual assault, Nimdok experimenting with prisoners in a Nazi concentration camp, and Ted being a con artist.”

Sears and Ellison had worked out the story for each of the game scenarios; the grim depiction of the five characters is one of the most notable and disturbing aspects of the game.

“Antihero” would undersell how horrible characters like Nimdock and Benny were in their former lives. It’s a harrowing journey, focused on the psychological anguish of each character, tormented by AM as well as their own sense of guilt over their past actions.

Unfortunately, by the time Sears had left, the game design document was only half finished, and a lot of detailed design work needed to be done before the game could be programmed.

“David was not available for me to consult with, and Harlan’s memory of his discussions with David about each of the game’s scenarios was hazy,” Mullich said.

With his experience designing a psychological thriller video game in The Prisoner, Mullich decided to finish writing the design of I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream himself.

“I worked pretty much on my own to fill in the details of the game,” he said. “This involved working out all of the puzzles the player needed to solve for progressing in the game, and expanding the few lines of dialog David had written for most encounters into full interactive conversations with branching choices.”

This was the case in the ethical dilemma that the character Gorrister faced in his scenario with the guilt he felt over putting his wife, Glynnis, in a mental institution. The resolution to that dilemma was for him to take his wife off of a meathook in a refrigerated meat locker, metaphorically taking himself off the hook.

“I recall as I discussed the scenario with Harlan, he rubbed his hands together gleefully and said, ‘No one is going to think of doing that!’ I replied, ‘Harlan, that’s the first thing gamers are going to try when they find Glynnis hanging there. That’s the difference between reading a story and playing a game–players take action.’”

Mullich added a few prerequisite steps to the scenario. His challenge, as he put it, was “not to make them so obvious that solving the puzzle was easy, but not so obtuse that they were arbitrarily difficult.

My approach was to add psychological meaning behind each of the steps, and I added context to the steps by the clues in which I gave the player, both through dialog with other characters and through the game’s hint system, the Cultural Encyclopedia — an idea that David Sears came up with, but I wrote all the entries and decided how and where they were to be used.”

He also visited Ellison’s home so that he could review his work. Mullich was already aware of Ellison’s reputation for being difficult to work with and combative in person. “He did not disappoint when I met him at his house in Sherman Oaks,” he said.

“I had come alone to show him the initial progress on the game, and he immediately started mocking me as ‘part of the Cyberdreams brain trust’ when I had difficulty finding an outlet for plugging in my computer, and it took me a few minutes to discover that the outlet was under (not just behind) a potted plant.”

“I ignored his insults, and proceeded to show him the game,” he said. “He seemed pleased, and when I told him that I had designed The Prisoner game and would try to put in the same level of literary sensibility in adapting his short story, he began nodding his head and I could see that I was gaining his trust.”

“He knew nothing about computers, and I could tell that, above all, he wanted his work to be well represented. Of course, my writing is nowhere near Harlan’s level, and when he grimaced at some of the dialogue I had written, I challenged him to do better.”

Fortunately, “he would then go into his office for about an hour and come out with some pages of revised dialogue. I wish he could have done this with all of my work, but Harlan’s time was limited, and so he was able to put his personal touch on a few interactions. For the rest, I had to do my best to mimic him.”

The biggest writing challenge Mullich faced was “to try to put myself in the mindset of each of these characters,” he said. It was dark material to channel, considering the trauma each of the characters has, from Benny dealing with his actions during war, Ellen facing demons from her past, and Nimdock recovering his memories at a concentration camp and realising he is the face of true evil.

Mullich drew on his real-life experience in writing the more horrific passages of the game. “At the time our infant son was undergoing chemotherapy, and after my workday at Cyberdreams was done, I would spend the night with him in the cancer ward of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.”

“Many of our roommates were older, and I’ll never forget the night when a teenage girl in the bed next to us woke up and had to have a nurse talk her through her fear of dying.”

Harlan Ellison As AM

When it came time to the game mechanics, David Sears had described a point-and-click system, but Mullich knew they couldn’t specify a user interface without input from the developer.

Cyberdreams no longer did its game development in-house at the time, so Mullich had to find a studio to do the programming and artwork for the game. He chose The Dreamers Guild, a studio founded by Robert McNally, who he’d first met when he was a teenager hanging out at Rainbow Computing.

McNally’s company had developed a game engine for their game Faery Tale Adventure, which it repurposed for I Have No Mouth. Mullich “adapted the design of the game” to “take advantage of the game’s features.

In fact, during the final weeks of production on the game, I stayed at their offices and did some of the game scripting myself so that I could do some balancing and polishing tweaks to the design.”

The environments reflected the twisted mental state of the five characters as well as the madness of the supercomputer AM. The art direction started with Ellison’s pointing out visual cues from the art and historical books that were part of his library, which numbered a quarter million books.

The art team drew from German expressionist films as much as they did fantasy as in Ted’s journey to a medieval castle where he counters demons and a wicked stepmother. Every set, from the sinewy Zeppelin fuelled by animals, to the electronic pyramid Ellen navigates, and the torrid jungle where human sacrifice scars the soil, is distinctively unnerving.

The artistic tapestry is intended to torture its victims with visual cues that trigger terrors from each of their pasts.

As for getting approvals from Ellison, Mullich showed “much of the art to Harlan, and I think he was happy with it–I don’t remember him asking for much in the way of revisions, anyway. Being a writer, he was more concerned with the story and the dialog.”

The voice acting is one of the best parts of the game. For this, Mullich gives full credit to voiceover director Lisa Wasserman. “I gave her a description of all the game’s characters, and she came back to me with voice samples of actors to choose,” he said.

The best voice, and a truly inspired choice at that, is Harlan Ellison himself playing the evil supercomputer AM. Mullich explained, “I first talked to John DeLancie, who played the mischievous god-like being Q in Star Trek:The Generation.

However, Harlan didn’t want anyone associated with Star Trek involved with the production — I think he was tired of always being associated with Star Trek — and knowing that he had done audiobook recordings of I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream, I asked, ‘Well, then how about you? I can’t think of anyone better to be an evil supercomputer.’ He agreed.”

Ellison himself opens up the game, and there’s both rage and glee in his voice as he declares: “LET ME TELL YOU HOW MUCH I’VE COME TO HATE YOU SINCE I BEGAN TO LIVE. THERE ARE 387.44 MILLION MILES OF PRINTED CIRCUITS IN WAFER THIN LAYERS THAT FILL MY COMPLEX. IF THE WORD HATE WAS ENGRAVED ON EACH NANOANGSTROM OF THOSE HUNDREDS OF MILLIONS OF MILES, IT WOULD NOT EQUAL ONE BILLIONTH OF THE HATE I FEEL FOR HUMANS.”

Ellison’s AM is as iconic as 2001‘s HAL, if not more so for the complexities conveyed in the killer supercomputer that vacillates between rage, amusement, boredom, cruelty, grumpiness, and joy.

Ellison himself was a self-avowed “Jewish Atheist,” and stated in a separate interview that when he wrote “about a God-like figure, which is what AM is, it has no mercy. It operates on the same scale as I perceive the universe to operate, which is that it is random.”

Wasserman directed the actors over several days of voice-over recordings, and Mullich was very impressed with her and the cast. The talent did an excellent job personifying the macabre sensibilities of the game, giving life to gloomy characters and conveying the gravity and weight of their grim fates.

Whether it’s Ellen wishing for water after not having had any for so long, or Benny describing each piece of food as manna from heaven, it’s no wonder Mullich found that “the recording sessions were actually my favourite part of development.”

The game’s music was composed and performed electronically by John Ottman, who was concurrently working as the editor and music composer for director Bryan Singer on his film The Usual Suspects. “As with Lisa, I gave John a list of what I wanted, and a couple of weeks later he delivered some of the most wonderful pieces of music I’ve had in any of my games. There was a theme for each character — all very different but all setting the right mood.”

There are multiple endings in the game, most of them tragic. Ellison put it more bluntly: “You cannot possibly win.”

Several conclude the same way as in the short story, with your player transformed into a “great, soft jelly thing” that wants to scream but has no mouth. But there is one, somewhat happy, ending that seems like a victory.

All three supercomputers are defeated and 750 humans that are cryogenically frozen on the moon are awoken with Earth being prepared for habitation again in 300 years. It can be reached if players act “ethically” and find some form of redemption for each of the five characters.

I asked Mullich if Ellison was ok with that ending. “If Harlan objected to any of these endings, I don’t recall being aware of it,” he said.

Super Computer Games

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream won multiple awards, including the “Best Dark Game of 1996” from Digital Hollywood and “Adventure Game of the Year” from Computer Gaming World. It’s also gathered a cult following and has found new life with its re-release on GOG from Night Dive Studio.

For Mullich looking back, “My goal for I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream was to honour Harlan’s classic short story by producing not just interactive fiction, but interactive literature — a game that would inspire the player to ponder and reflect about the human condition,” he said. “With all of the awards the game won at the time, I think that I was successful in honouring Harlan’s work.”

“But I also wanted to inspire future game designers and writers to create stories that were more than just slaying a dragon or stopping an invasion. I’m not sure that my own work actually influenced anyone, but I am very gratified that story-based games have evolved on their own to the point where quality game writing is now recognised by the Writers Guild of America. I got into video games because I saw the potential of games as serious creative medium, and now, 40 years later, I think that we are beginning to fulfil that potential.”

He does have two regrets from his time working with Ellison. “I’ve been told that Harlan’s home has secret passages, heaps of memorabilia, and shelves full of manual typewriters, but I’ve never seen these and I regret I never asked to see them during one of my visits. When he went off to his office to rewrite some dialog for the game on his manual typewriter, I would sit at the kitchen table and contemplate the crawling Spider-Man figure suspended from one of his kitchen cabinets.”

“I also regret never having maintained a friendship with him after the project was finished. Every once in a while, I thought of calling or writing him, but I never thought of a good excuse for disturbing him.”

Mullich would go on to join The 3DO Company and lead the development of Heroes of Might and Magic. After The 3DO Company shut down, he joined Activision to produce Vampire: The Masquerade Bloodlines. He’s currently the Faculty Lead at the Los Angeles Film School’s Game Production Group and does independent consulting work.

With decades of experience, I asked what he thought about gaming in its current state, as well as its future. “While game platforms and their capabilities have technologically evolved over the history of the game industry, we may see platforms that leave the number-crunching to the cloud as game distribution shifts from retail stores to digital storefronts to streaming services,” he said.

“Once that shift happens, the big game publishers may turn out to be cloud-based services like Google, Amazon, and Netflix rather than Activision, Electronic Arts, and Nintendo. Virtual reality now adds the extra dimensions of physical movement and 360 views to gameplay, but except in location-based facilities set up so that people can freely move around wearing VR headsets without crashing into the coffee table, I’m more optimistic about augmented reality eyewear as a gaming device.”

Still, the lessons from Ellison’s story resonate: “Having worked on paranoia-inspiring games like I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, I do have to admit some trepidation about giving larger and larger computers more immersive and direct access to our brains, even when playing a game,” he said.

“Maybe that’s why I spend more time playing board games these days.”

Comments

2 responses to “How Harlan Ellison’s Most Famous Short Story Became An Amazing Video Game”

Awesome read.

Re: today’s static podcast (If We Create Perfect Artificial Intelligence, Should We Let It Rule Us?) I’m going to go with no.

One of the scariest things I’ve ever read is the image in the original story of one of the characters being tortured. They had their eyelids clamped open, and a razor-blade slowly approached….

*shudder*