Is it possible to care about Sonic the Hedgehog? Can a person really be concerned about Sega’s blue creation and what happens in his worlds? The answer is yes, but it depends on where you encounter him.

I don’t think that Sonic is a mascot. He may act like one sometimes. He’s certainly not a real person, either, and he’s barely a “full-fleshed character”. Yet he’s more complicated than a collection of big ideas used to sell a product. Rather, Sonic exists somewhere on a spectrum between the product-face and what we can call a “real person”. He constantly moves between the two, rarely touching the first end and never reaching the other, even though there’s a clear aspiration to. We can say then, that Sonic as a media object is fluid. And when asking the question “If Sonic isn’t a Mascot, then what is he?” seems to have as many answers as there are pieces of Sonic art and media.

Every video game, comic book, fan fiction and media piece about Sonic is a negotiation of Sonic’s relationship to his mascot image. In the Sonic The Hedgehog comics from Archie, there were visible attempts to pull Sonic as far from the mascot as possible, into a point where he could, hopefully, feel ‘human’: a complex, layered person who could be related to and meaningfully engaged with.

The video games, on the other hand, seem to do the opposite, as among the decades we’ve seen Sonic devolve from an ambiguous character into the pure Mascot object that makes something like Sonic Boom so horrifying. I’d like to go over a few Sonic games, some specific points in the comics lore, as well as some surreal Sonic art pieces, in hopes of capturing the spectrum that is Sonic The Hedgehog, as best I can.

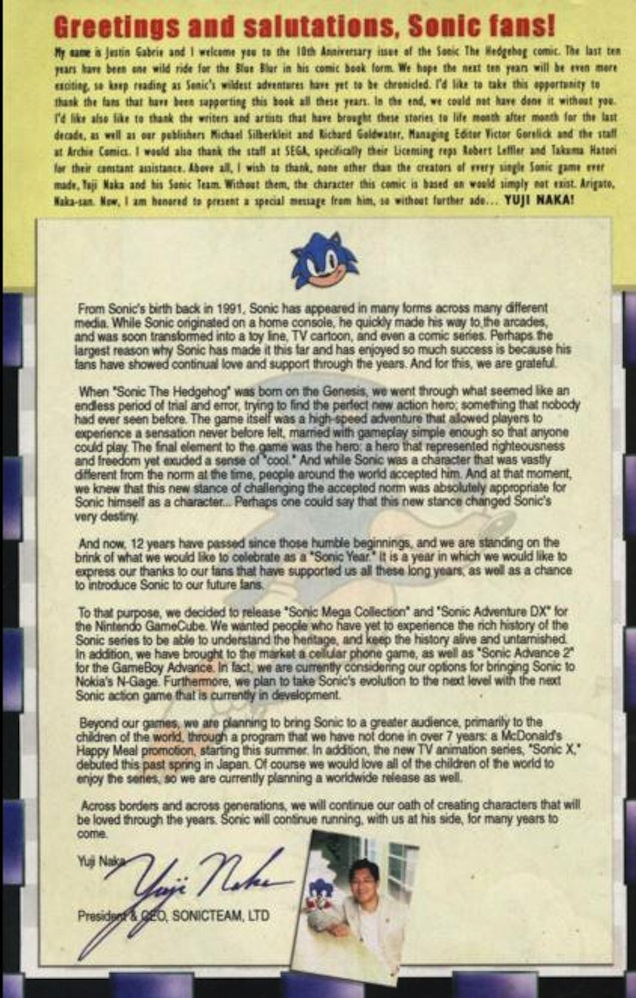

If you looked in the back of issue 125 of Archie’s Sonic The Hedgehog comic, you would find a letter written by Yuki Naka, an anniversary letter, to commemorate 10 years of the Sonic franchise. In it, he announces Sonic Adventure DX and Sonic Mega Collection for Nintendo GameCube, as well as Sonic Advance for the Gameboy Advance, a “cellular phone game” for mobile devices, and franchise tie ins: a McDonalds Happy Meal promotion, and the announcement of a new anime series called “Sonic X”. But before he does this, he takes a moment, in his own words, to discuss what Sonic means to him, what the idea of Sonic is and was supposed to be:

“When “Sonic The Hedgehog” was born on the Genesis, we went through what seemed like an endless period of trial and error, trying to find the perfect new action hero; something that nobody had ever seen before… The final element to the game was the hero, a hero that represented righteousness and freedom yet exuded a sense of “cool”. And while Sonic was a character that was vastly different from the norm at the time, people around the world accepted him. And at that moment, we knew that this new stance of challenging the accepted norm was absolutely appropriate for Sonic himself as a character.. Perhaps one could say that this new stance changed Sonic’s very destiny.”

Sonic The Hedgehog was conceived during a time when the idea of individual rebellion seemed inextricably linked to consumer culture. We can think of the 1980s as a point of large political and economic shifts. The structures that allowed social welfare programs, government support, and government intervention into corporate practice began to dissolve, as there seemed to be no political or philosophical justification for their expansion, especially under the economic crisis of the 1970s.

What began to emerge in its place, as a new dominant political ideology, was a “market-driven” thought that argued not only for the deregulation of markets, the freedom of corporate practice, and the dissolving of collective social welfare programs, but did so as part of a larger political project: to reinstate a political and economic elite, whose power was blunted through unions and activist organising of the mid-20th Century.

Political theorists like to call this “Neoliberalism,” and we can probably say that it was, above all, a mission to bring back the 1%, and the cultural norms that keep the 1% in power: greed and individualism over collective power; meritocracy, the idea that those in a place of power and success are there because of their individual strengths and not their privilege and inherited wealth; and capitalist realism, the construct that places capitalism as the most rational and “sensical” social-economic system, the only kind of that “makes sense”.

“Sonic always carried potential to be interesting, but Sonic games seem to have progressively dissolved this potential.”

How did ’90s culture respond to the rampant corporatism and hard individualism pushed by political elites in the late ’70s and ’80s? Leigh Alexander has written about the “quiet revolution” of 90s youth, whose mode of resistance was idleness — doing nothing, as opposition to climbing the corporate ladder, and prioritizing reflection and the existential self over the aggressive pursuit of individualist success and capital gain. But it’s important to point out that the response of 90s culture to these political changes was also to perform rebellion through consumerism, to create a sense of alterity through buying products.

Even in the ’80s, advertising and pop media culture pushed to associate the performance of rebellion with the consumption of their products, whether it was trying something “new” by drinking a Pepsi instead of a coke, or resisting the conformed masses by buying a Macintosh over a PC, or even showing your friends how ahead of the curve you were by buying a Sega console. This was the myth of consumerism’s reciprocity, that through buying consumer products I can realise my existential desires, fulfil the fantasy of rebellion, and perhaps deal with the feeling of lostness and adriftness that Alexander notes was pervasive among her generation.

Nowhere is it more apparent that Sonic fits into these dynamics than Naka’s note itself, where vague platitudes of coolness and “challenging the norm” weave between video game content announcements and McDonalds cross-promotions. This is what a Mascot is meant to do, to embody a loose collection of large ideas and attach itself to material, commoditized objects. Sonic, among many other commercial images of the 1980s and 1990s represents the commodification of alterity and rebellion, rendering these concepts less useful, and less capable of inciting change and meaningful social transformation.

Sonic and Video games

What surprised me the most, playing through the original Sonic The Hedgehog again was how different Sonic was from how he was always externally projected. The Sonic that’s implied through advertisements and the external framing that includes Naka’s letter, doesn’t reflect how Sonic is shown in the games themselves, where his action and presentation is quite modest.

Sonic’s accomplishments are never framed as extraordinary or miraculous, and the radical-attitude personality isn’t really apparent in his character, despite that little finger-wag at the Start Screen and Stage Clear. You can argue that Sonic the Hedgehog isn’t really about Sonic at all. The game seems to put more energy into its setting, tone and mood through its soundtrack, and its use of texture and colour. Sonic can be understood as more of a vessel towards exploring and engaging with these elements, than an object that circulates attention around itself and the product-object, like we would expect a Mascot to do.

In that sense, we can say that Sonic’s relationship to the Mascot object in Sonic The Hedgehog and its Genesis sequels is quite ambiguous. The suggestive nature to Sonic and his presentation actually makes Sonic more interesting. We’re compelled to not just think about Sonic but rather Sonic’s place within something larger — a larger universe and fiction that is all at once symbolic, historical, and political. I’d say that Sonic’s relationship with players in these games is much more meaningful. There’s always been a tension between the pervasive marketing of Sonic and the way Sonic actually *is*.

All this changes quite drastically when Sonic Adventure is released in 1999. Sonic Adventure marks the beginning of a trajectory for Sonic that we can argue is still on course. With the inclusion of voice acting, cutscenes, dialogue, monologue and a more plot-focused and character-focused narrative, 3D Sonic games became a project to fully realise and materialise Sonic as The Mascot. And as such, we start to see Sonic degrade into a flat, lifeless husk of a character, who spits out slogans and generally has only one personality mode, the radical attitude dude, the sad recycled image of vague ’90s cultural concept.

I think Sonic Heroes was the first Sonic game where I was compelled to mute the television because the dialogue and cutscenes were so hard to bear. I’ve done the same in every Sonic game I played after; Sonic and the Secret Rings, the whole Sonic Riders series, and the text conversations in Sonic Rush: Adventure for the DS. I watch Sonic Boom gameplay videos now with the audio low, wanting to hear the sounds but dreading the cheesy one-liners and awful Pixar-inspired music that plays in sequence.

As Sonic and his friends became more boring and obnoxious with every instalment , Sonic himself seemed to be getting closer to the Mascot construction that he was always meant to embody. Sonic was created as an object that can be plastered onto things like, say, an Olympic video game tie-in, and yet the results these mergers never seemed right. I never had a problem watching Mario drive karts or play tennis and yet it’s disturbing to watch a sad, frowning Blaze the Cat on ski-shoes with a target gun.

It’s not comforting or disarming. Rather, it’s awkward and uncomfortable, knowing that these characters have histories, motivations and character that are being metaphorically gutted for the sake of being cute character stand-ins. The truth about the Sonic games’ central conflict is that Sonic never worked very well as a Mascot. Not the way that Mario always has. Sonic games, and Sonic media by extension were always a little bit political, they always carried subtext, formal or textual, that was incompatible with the requirements of the Mascot construction. Sonic always carried potential to be interesting, but Sonic games seem to have progressively dissolved this potential.

Sonic in Comic Books

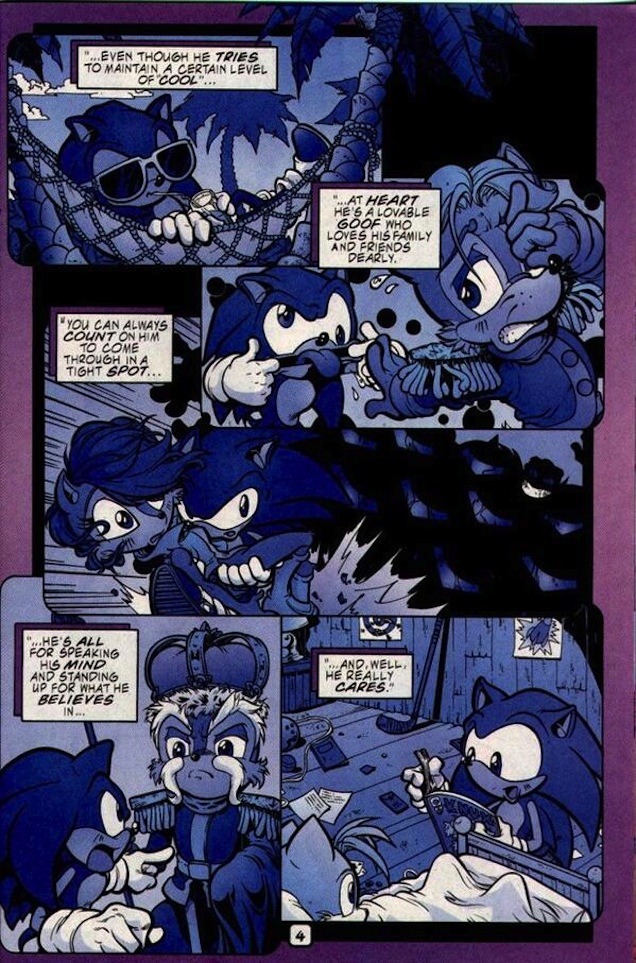

I think the best way to communicate how Sonic is in the comic books is through plainly showing a few key panels with brief explanation:

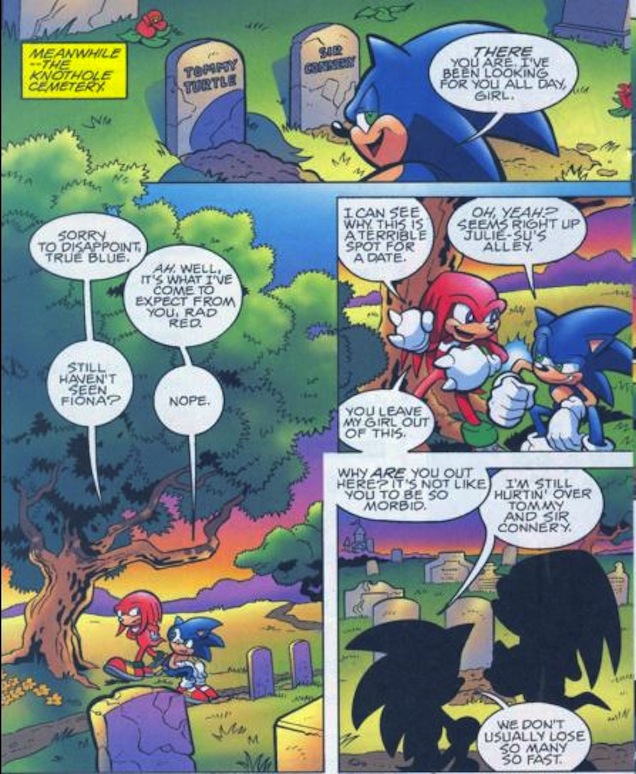

1. This is Sonic visiting the grave of his friend Tommy Turtle:

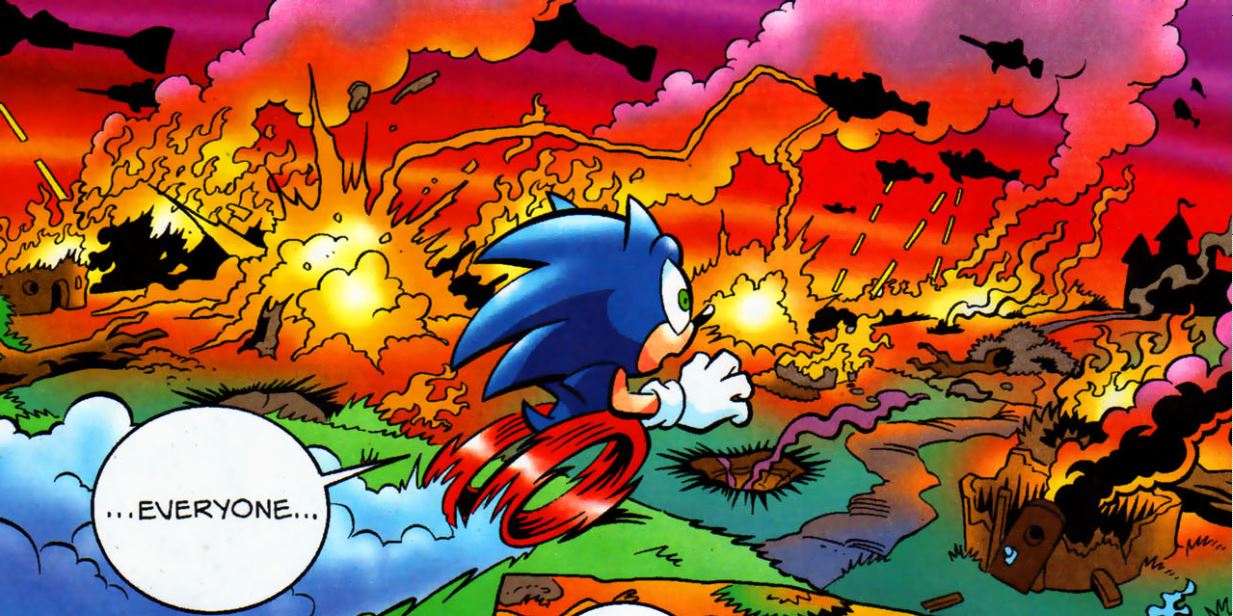

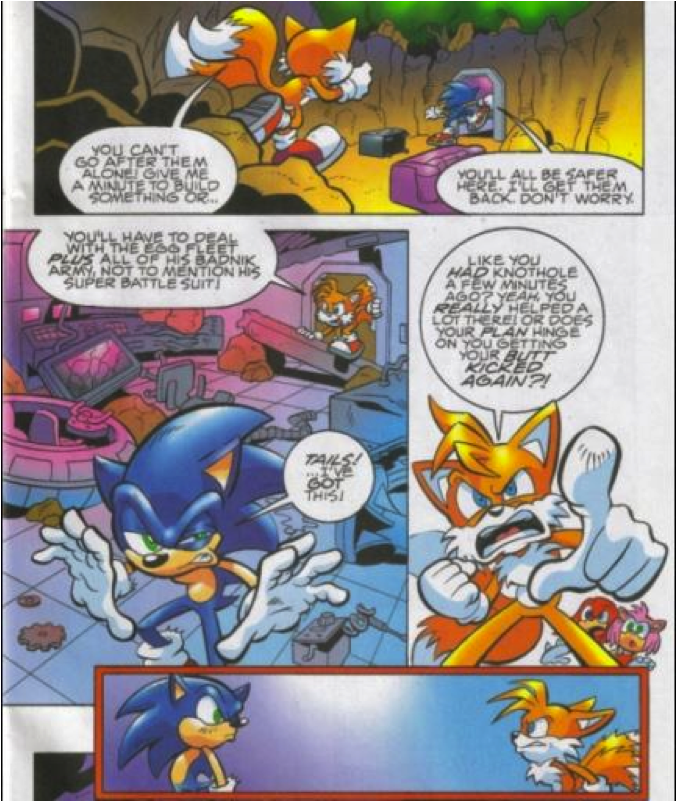

2. This is Sonic coming back to find that his entire town has been bombed to the ground by an air fleet.

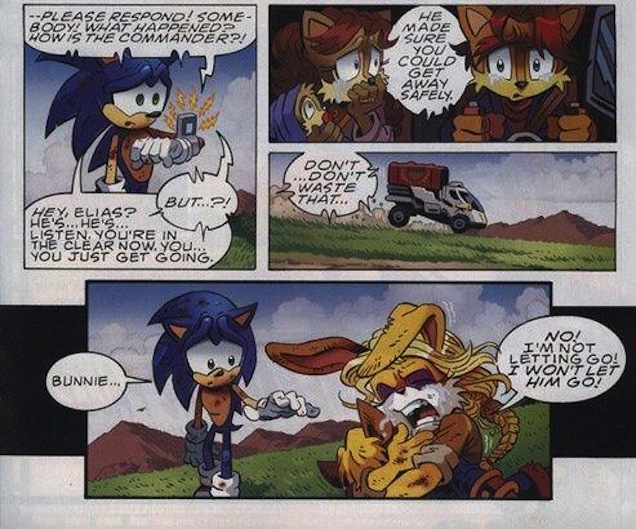

3. And this is Bunnie Rabbit clutching her husband after watching him get hit by an explosive, and Sonic reassuring her that he’s still alive:

My favourite panel focusing on Sonic would have to be a concluding panel of the EndGame story arc, Issue 50, where Sonic approaches a “dead” Sally Acorn, princess of the Acorn Monarch and his life-long crush. Sally was presumed to be dead after a deadly fall in Robotropolis, and Sonic is seeing her for the first time since he was accused of her murder and exiled from Knothole Village.

This scene, omitting text or bubbles of any kind, is important because it totally dismantles the construct of Sonic as a mascot. There are no characteristics of the radical-attitude dude archetype that he was created to embody. Sonic is not speeding but tip-toeing as he approaches her, his eyes slanted, his arm reaching out, preening to touch. He’s not brash or impulsive but cautious and hesitant. He doesn’t appear confident or heroic, but expresses concern, hesitancy and empathy. The panel itself is bordered by two tree trunks and their leaves.

It’s enclosed, and gives intimacy and a sense of privacy to this moment. And as viewers, watching between the tree trunks, it almost feels like we’re peeking at something we’re not supposed to be. Scenes like these with Sonic aren’t common in the comics, which makes them all the more exciting when we do see them.

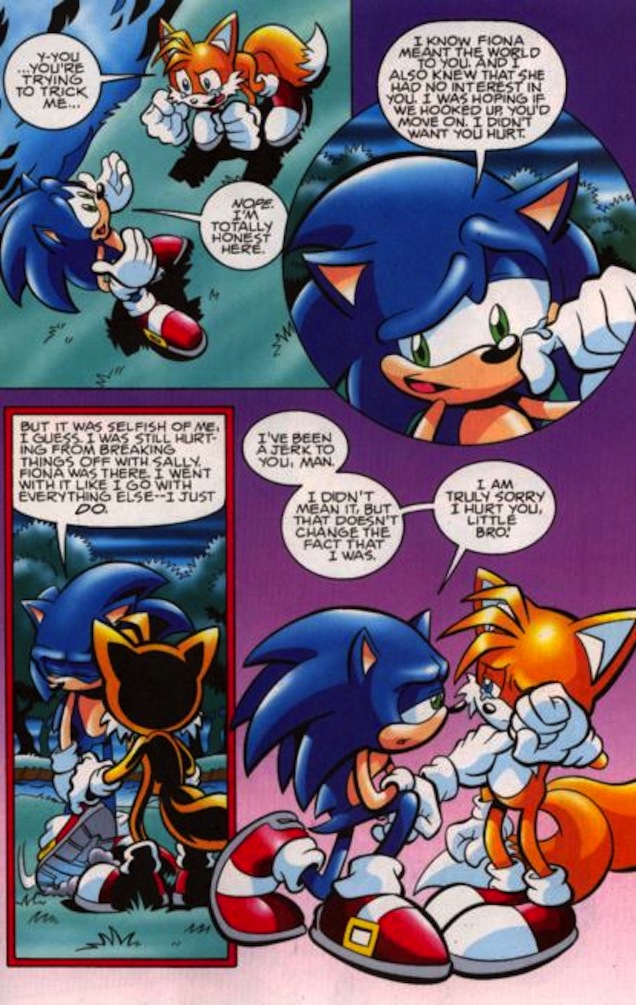

The Sonic comics don’t ignore the mascot contextualization into Sonic, instead they play with Sonic’s general traits and stretch them to their logical extremes. If Sonic likes to contextualize himself as a Hero, then what happens when he can’t save those he’s sworn himself to? If Sonic is arrogant and impulsive, then what happens when his impulsiveness hurts the people he cares about? And how does Sonic respond when he comes in conflict with the flaws of his naive, idealist aspirations towards heroism and moral absolutism?

And yet, when he does respond, Sonic displays his most important characteristic, which is his ability to reflect and his capacity for empathy. I’ve never played a Sonic game and felt like Sonic really gave a shit about anything around him. But here, Sonic questions, conflicts with, and reasons through the flaws of the Mascot construction. Sonic demonstrates constantly that he really does care about the people around him, including his friends, his family, and his community. Sonic often is a legit admirable ‘person’.

This is what pushes Comic Book Sonic to feel like a “real person,” someone who expresses ideas that are interesting and with whom readers can create a meaningful relationship. The Sonic comics push Sonic as a *character*, into important thematic areas that other Sonic media fails to do.

Sonic and The Internet

Through the streams of twitter and “weird internet” culture, Sonic has found another way to become something much more than a Mascot. Sonic on the internet is actually quite otherworldly. His image is often twisted out of context, creating strange, surreal and freakish constructions that are also funny and entertaining.

Yeah, why? pic.twitter.com/396BP5dKTs

— chris person (@Papapishu) July 17, 2014

Submitted by @TheMTwinny pic.twitter.com/7TwFvVqMmI

— Bad Sonic Fan Art (@BadSonicFanArt) April 5, 2014

@BadSonicFanArt #dr.eggman #tails soul calibur 5 pic.twitter.com/FGd2hFs4Yw

— Jake might be a robot (@JakeMacKay3) July 18, 2014

@TheLaq pic.twitter.com/x5CXPmkaKm

— Sean-Paul (@HelloMrKearns) July 23, 2014

These tweets and images are more interesting than the “washed-up celebrity” depiction of Sonic that you would see in Flash movies 5 or 10 years ago. Instead, these kinds of “weird-Sonic” internet objects engage directly with Sonic’s Mascot construction. Sonic is broken down, decontextualized, and the mascot is stripped bare of its pretentions, revealing the absurdity and contradiction of the founding ideas that Sonic was built on, the ideas that people like Yuji Naka glorify.

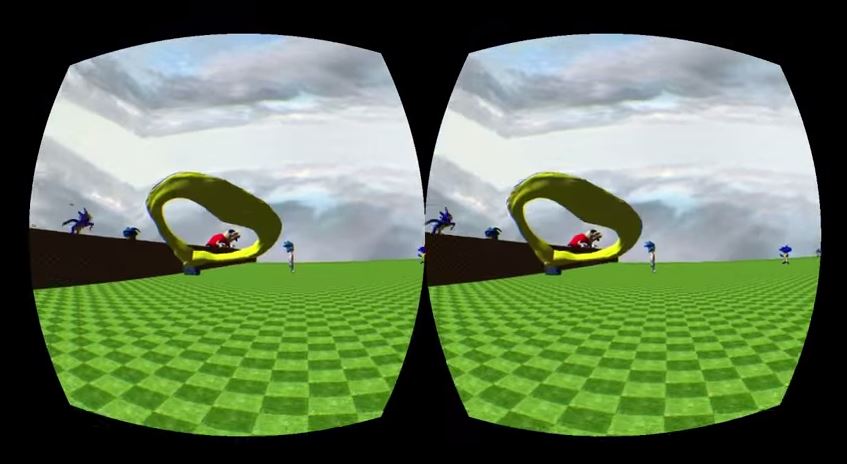

Video games are where Sonic was born, where he goes to die and where he lives in afterlife. As such, the best example of a weird-Sonic art piece is probably Sanic ’06, an Oculus Rift game made in the Unity engine.

Sanic ’06 is titled after 2006’s Sonic The Hedgehog, an infamous 360/PS3 reboot that’s regarded as among the worst Sonic video games ever made, and one of the worst titles of that year.

Sonic The Hedgehog was slow and repetitive, and its levels were gruelingly long, averaging between 10-20 minutes of inaccurate platforming, with tedious fetch quests, and bloated, vapid mini-game sections. Sonic The Hedgehog was hard, it was boring, and it didn’t seem to reflect the ludic or aesthetic values that made Sonic games interesting to play. It’s understood by many as the pivotal example of Sonic’s steep decline as a media object, and is probably the first game that comes to mind when someone will argue that Sonic is “dead.”

So even through its title, Sanic ’06is actively engaging with the thematic “Death of Sonic.” The game can be understood as a sort of epilogual piece, a reflection of the meanings of Sonic “after Sonic.” What does it mean for a Mascot to die? And what truths do we uncover about Sonic upon his death?

Sanic ’06 is a display of two ceiling-less ‘rooms’ containing various 3D models, each of them a different depiction of Sonic or Sonic’s side characters. Like a bad wax museum, each model is ugly and freakish, spanning between the humanoid, the odd-legged creature, the gross monstrous depiction and the non-applicable. Some of them move and pulsate erratically like a graphical glitch; others will zip sporadically across the rooms at their own leisure, or follow you around at uncomfortable proximity to your avatar model. But many will just sit completely still.

These models are cold and unmoving, and they populate the space and create an air of tension and of creeping anxiety. When you move up towards them, they will each play a small sound clip from a piece of voice acted Sonic media. The Shadow model, for example, will play a clip of Shadow saying “Damn” without context, which I assume is from 2005’s Shadow The Hedgehog, and the Silver model will play the infamous “IT’S NO USE” line from one of Sonic ’06‘s many intolerable boss fights. Many of them play various clips of Sonic dialogue from the Sonic games, some of them edited to sound more unfamiliar.

The game plays the Green Hill Zone soundtrack on repeat, and the floor is the staple checkered green-yellow. The rooms are populated with ugly defunct “rings” that float with low gravity physics and when touched, utter the “rings sound,” but its presentation betrays the addictive click that rings were designed to make us feel.

“I’ve never played a Sonic game and felt like Sonic really gave a shit about anything around him.”

From merely watching the video, it’s apparent how Sanic ’06 is surreal and nightmarish. And yet, most of it is composed of parts from existing Sonic games. Sanic ’06, like other weird “Sanic” pieces, merely rearranges the existing parts of Sonic media to transform it into something strange and unfamiliar. Sanic ’06, then, doesn’t imagine the death of Sonic as a literal death, or the “washed-up celebrity” trope that Sonic fans are used to, but the point where the internal logics of Sonic, everything we use to understand and identify something as Sonic media starts to break down and dissolve.

If the Mascot relies on familiarity and ease of understanding, then the death of the Mascot would imply the destruction of these ideas. Every audio piece, visual cue, or textual reference in Sanic ’06 is twisted and de-familiarized, and we become trapped in a world where nothing is readable or parsable, where our world stops making sense. The fluidity of Sonic’s image, demonstrated through these models, is only an acknowledgement of Sonic’s inherent brokenness. If Sonic truly is dead, then Sanic ’06 is the autopsy, and we’re seeing the pieces of his failed organs.

When Sanic ’06 imagines the Death of The Mascot, it imagines the death of key cultural constructions that came with objects like Sonic The Hedgehog. The sidelining of consumer capitalism after the 90s — the waning of consumer demand, and the expansion of the credit system as a response — is also the weakening of the safeties and comforts that consumerism was able to provide. The myth of consumerism’s “easy exchange”, the idea that I can buy the embodiment of rebellion against a system I can’t control, and fulfil the yearning for alterity through cultural “placebos”, these products, has sort of dissolved, and is now supplemented with a culture of nostalgia and an economy that preys on your attention.

The ’90s kids have grown up into a world that’s only become increasingly precarious. They are now burdened with extreme debt, unable to find stablework, and plagued with widespread depression, anxiety, and loneliness. Things seem to have only gotten worse for the ’90s kids. Or perhaps things were always bad. Only now, there isn’t any consumer product to reassure us, no “Teen Spirit” to guide us, and no hedgehog fast enough to save us.

Zolani Stewart is the founding editor of The Arcade Review, a digital magazine about experimental games and art. He’s also a huge Sonic nerd, in case that wasn’t clear. You can follow him at @Fengxii.

This article was originally published on 5/8/14 and has been updated since its original publication.

Comments

6 responses to “Sonic, Then And Now”

I actually vaguely remember the EndGame comic arc! Yay me for recalling obscure knowledge from some 12-15 years ago

Don’t have time to read the whole thing as I’m at work. But sonic IS a mascot. He’s my mascot of gaming in the 90’s.

It’s a shame that no one ever mentions the UK Sonic comics. It might have been competitively short lived but in my opinion it was better than the Archie series.

That first image makes me want to go back and play the original Sonic games. I’ll make do with the Sonic side scrollers on my Nexus 5 tonight just for the sake of the good old times where games were simple and actually fun.

That screenshot at the top of the page! The music on that level is my ringtone 😀

All this and no mention of the bafflingly weird and by now infamous appropriation of Sonic and co by Christian teenagers in bizarre comics and stories on the internet?