I was perfect in a video game once. And that video game was perfected in me.

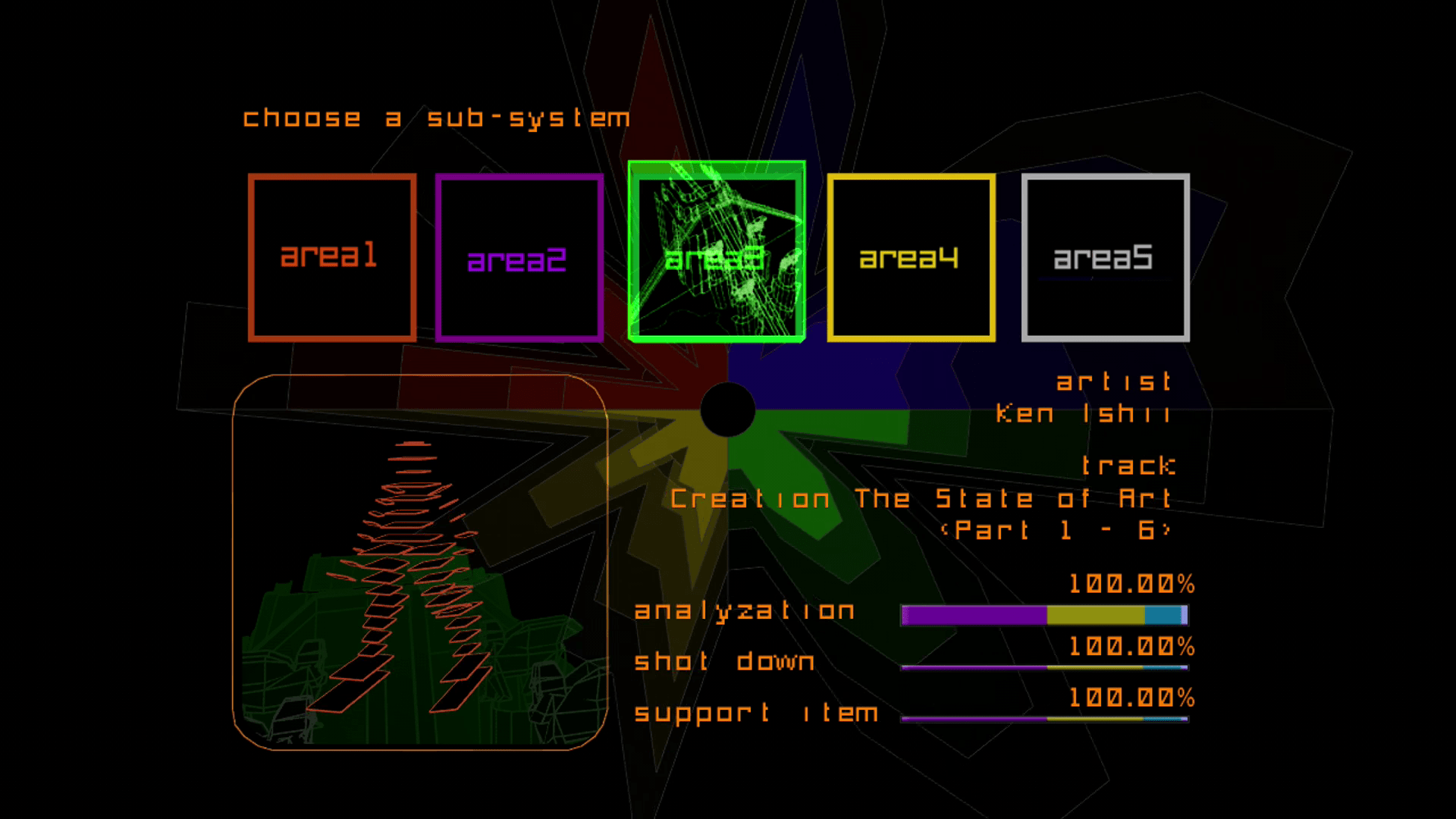

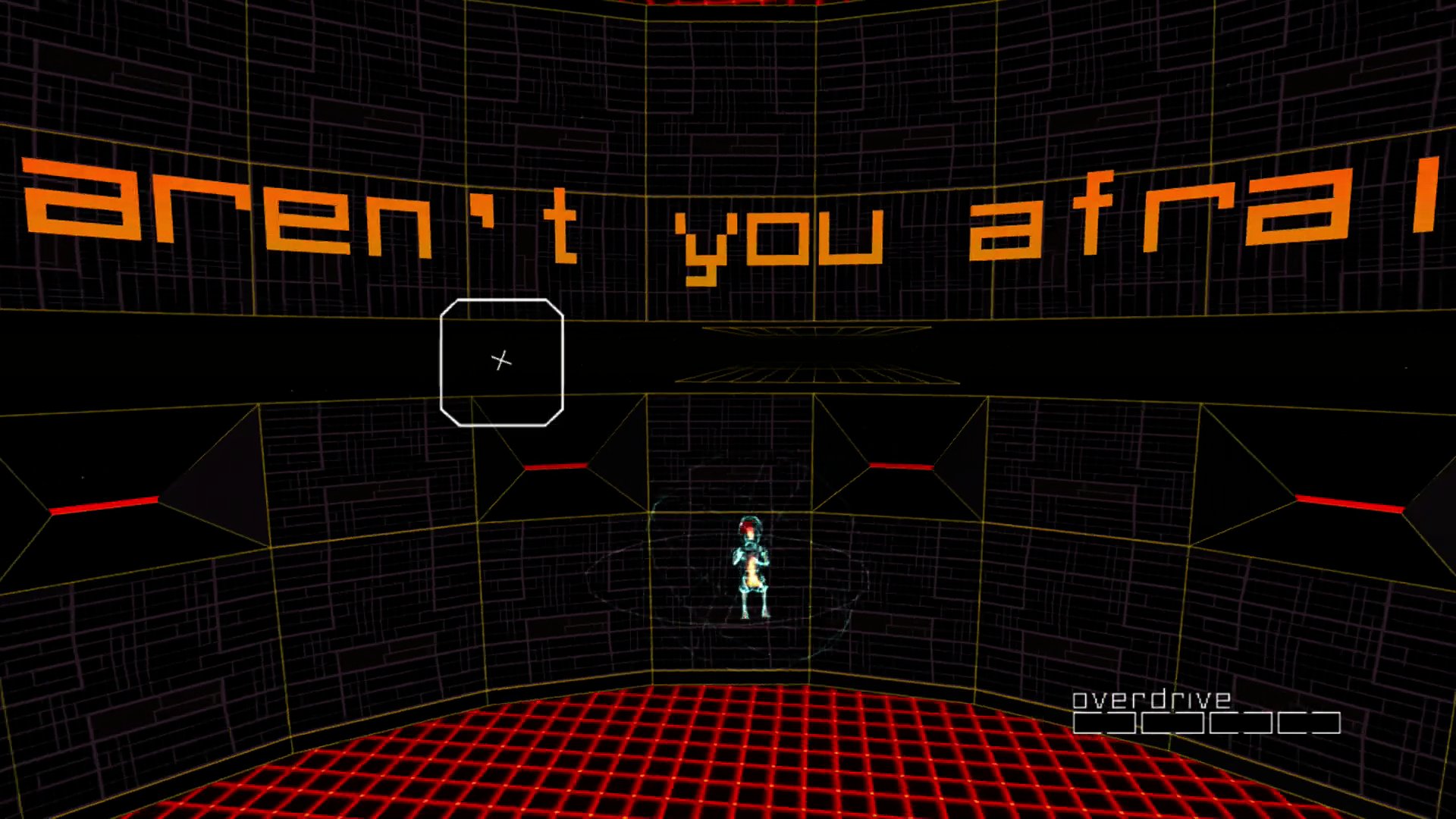

See that up there? That’s the best I’ve ever been at anything in a video game ever. I don’t even remember doing it but there it is, perfect and improbable. Just like the game I did it in. Just like Rez.

The first time I encountered Rez was during its release on the PS2. I was writing about video games for Teen People magazine and took a meeting with a PR person to see the game. It was my first look at Rez ever since I skipped out on owning a Dreamcast, the console where the Sega-published game debuted. Looking back at that meeting with a decade-plus of distance, I’ve realised how quixotic an endeavour it was to try and get mainstream press coverage for such a weird, trippy creation. The tagline for the game’s marketing was “Rez requests your senses. Are you game?” Turns out I was.

I’m the type of player and writer that fights mightily against the gravitational pull of nostalgia. Sitting around thinking that things were better in the old days is a good way to create a living hell out of the present. But Rez forever has a hold on my gaming soul. It was one of the first games to make me aware of my own nervous system, of the twitches and fidgets rattling through my limbs. And it made music out of them, letting me hear how my involuntary reflexes sounded when given voice through a hi-hat. I realised how much I was mashing buttons and how chaotic and catchy my impatience could sound. [Note: All the images and video in this post have been captured off the 2008 Rez HD Xbox 360 release.]

The now-defunct United Game Artists studio that worked on Rez — led by Tetsuya Mizuguchi — understood how to create anticipation, teasing you with bits and pieces of a grand tapestry multiple times over. Better still, they managed to have crescendos be amazing every damn time. Take the first chunk of Area 1, for example. It’s musically spare and interactively sparse, a gentle lead-in for the play concepts that will follow. Four or five levels zip by before the song you’re going to be playing inside of starts to really blossom, coinciding with Rez‘s first true instances of challenge.

As the game unfurls, the player is forced to reckon with his own responses to it. Do you target for speed, mashing as quickly as you can to down targets? Or do you target for rhythm, holding the reticule to lock on to the maximum number of enemies? Rez doesn’t judge, offering a musical incentive for either method. Mash buttons and your inputs generate drum sounds that add to the thumping electronic soundtrack. Max out the target lock and you hear a choral burst to let you know you can let go and loose your beam attacks on the threats. I find myself constantly switching between either approach to hear the sounds talk back to me.

Rez taunts you with perfection, dangling all the instruments you’ll need to create fleeting moments of video game nirvana: avatars that move like yogis, vibrations that mimic heartbeats, lasers that sound like old synthesisers and enemies that explode into astrological sign nebulae. Homages to the vector-based graphics systems of the past. Beautiful colours in either sharp contrast or harmony with each other. It’s generous and expansive, like Mizuguchi and company were building a digital revival tent of love, sensation and music.

At the same time, it’s fucking hard as hell. All that beauty is also feeding you vital information. That tentacle-having boss form at the end of Area 2 sure is entrancing, right? The way it moves along with the undulations of the bassline? But, hey, you better notice that subtle camera drift that’s bringing you right into the line of fire coming from its arms, too, or you’re not surviving this encounter. And if you don’t read, say, the colours of the lasers on the Area 3 boss’ first mutation correctly, then you won’t know which ones will come out in two diagonal directions. And you’ll get hit. Don’t get too distracted by all the pretty. Connect with it, yes, but live inside it, too. Stretch that mind, caterpillar. It’s the only way you’ll become a butterfly.

You might look at the classic Dreamcast game and see a relic, a collection of visual and thematic clichés that inextricably tied to quickly outdated notions of hacking and artificial intelligence. But, to me, the blocky, non-representational graphics have actually helped Rez age well. It was only ever meant to portray something ethereal and non-existent. There’s no real cyberscape, after all, so it can’t fail at being an accurate, photorealistic representation of one. It’s influenced by forebears, to be sure. You can see parts of Tron, old Atari 2600 games, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in there and can feel the zeitgeist of cyberpunk and rave culture in Rez‘s DNA. But the game makers took those things and remixed them into something unique.

The embarrassing plenitude of capital-S symbolism makes the game ripe for being called pretentious. Yet it’s that 3-a.m., blazed-out-of-your-gourd earnestness that endears Rez to me the most. Why would you put a neurotic AI asking existential questions in a game unless you want that stuff to touch people? If you wanted to make a cool boss fight then make a cool boss fight. But, in all its heavy-handedness, it’s clear that Rez‘s denouement is supposed to mean something more.

It feels incredibly hokey to say that Rez is one of a rare few games that evokes a sense of spirituality in me. But it’s true. Watching video of my sessions from last night and this morning feels like a disembodied experience: Did I do that all? Was I really moving that fast? How come I can’t feel the vibrations now? Part of it is the intense focus on swarms of moving targets and how Rez‘s synaesthetic design binds sound, visuals and haptics so tightly together. I become awash in sensation while playing Rez and I always feel different after I’m done. Always. Like I have to re-align my vibrations back to this reality. Always.

It’s a game that grapples with messy paradox yet it tempts you to bliss out at every available opportunity. Don’t let your eyes roll back too far into your head, though, or else you’ll miss the 7 missiles heading your way. It looks backward and forwards at the same time. It imagines a world where being always connected to the sensations of a global internet would bring fear, distrust and then finally enlightenment. It’s also an example of experimental games weren’t immediately dismissed as having no commercial prospects. Rez was ushered out into the world to find its own place. When I wrote about Eric Chahi’s classic Another World being ported to the latest generation of game hardware a few months back, I talked about how it’s one of those games that should just be constantly present and readily available to play, no matter how market changes may shift reality. Rez is in the same category. It’d be a damn shame if it doesn’t find a home on this generation of game hardware.

Comments

9 responses to “Rez Is Still A Near-Perfect Video Game”

I only had a go of this at the Powerhouse exhibition last year after having heard all manner of praise for it over the years. Didn’t really get it. From what I could tell you just hold down the button and “paint” over the enemies on screen with the cursor, then release. Then keep doing that. Don’t know what I was expecting exactly, maybe something a little more rhythm-y, but it felt like it fell short.

Did they have the vibrating sensor(s) available at the time you tried it? The PS2 version game with a separate, single vibrating pack that would vibrate in time with certain parts of the music, whereas the XBox 360 release instead used up to 4 controllers to do the same thing. For me, that’s what took it over the edge.

I never got to try the PS2 pack, though I hear the strength of vibration was vastly greater than the 360 controller. However, having 4 controllers spread out at various points (either on the one person or shared between a few) was quite the experience.

I assume someone will now proceed to make a joke about the particular location(s) of the controllers/pack.

I can’t remember if they just had it on display or if I’m thinking of seeing it somewhere else… it might have just been rumble through the controller? It’s hard to say.

Rumble does make such a huge difference though. I refuse to play Elite Beat Agents without the rumble pak. Space Invaders Extreme is the same too (which is a shame, since I’d like to use the paddle controller with that but it’s gotta be one or the other).

Ha. I was beginning to think I was the only one who’d even tried EBA with a rumble pak. And, same as you, I can’t really play properly without it. I was disappointed when Nintendo phased out the GBA slot-2 mainly for that reason. Your post has made me want to dig out my old DS Lite and give EBA another go.

In this day and age of graphical fidelity and VR coming soon, tactile feedback seems to have fallen by the wayside. Even something as simple as that tiny vibration on a single failed note makes a huge difference to the game experience, and people seem to have forgotten about it.

On the VR thing, have you checked out Tactical Haptics at all? Pretty amazing stuff, I was really hoping for it to hit its kickstarter.

And yeah, GBA slot 4eva. I was disappointed when the 3DS launched without any kind of rumble. Also that there was no rumble in the Circle Pad Pro. I’d given up by the time the n3DS came around, but I guess now I have retrospective disappointment 😛

I somehow missed Tactical Haptics, thanks for the link. Something like that better integrated into motion controllers like the Hydra would be awesome, although I wouldn’t discount the feeling good ol’ rumble can give in the right situations. A combination of both might be good.

I always wanted (and still do) a Novint Falcon, and their Xio using the same tech looked very interesting, if a bit too ambitious.

I’m pretty sure the STEM (basically Super Hydra, if you missed that one too) is supposed to have rumble in each of the trackers you can attach to yourself, so I guess if it was used with a TH controller then you would get to have both.

No joke, the Trance Vibrators were kinda infamous for being put in certain places 😛 I just sold 90% of my game collection including about 5 trance vibrators still factory sealed. Those things were flipping great.

I love this game and I love this article