You’re looking at a screenshot I took of a video game that I just finished playing on Steam.

Here is a clip from another game I played on my PC this week:

Earlier this year, I played a game on my PlayStation 4 that looked like this:

Movies these days — or action movies, at least — are a nearly seamless mixture of computer animation and live-action footage. When Brad Bird, the director of animated films like Ratatouille, The Incredibles, and The Iron Giant, was tapped to direct Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol, the move seemed an entirely natural transition. Who better to oversee the CGI sequences in a 21st-century film than one of our most skillful directors of cartoons?

Video games, on the other hand, have been slow to integrate what once was called, redundantly, “full-motion video.” Maybe the hangover from the 1990s dabbling with “FMV” on CD-ROMs is finally starting to wear off, because in 2015 I keep playing video games that look — at least in part — like live-action television shows and movies. More are on the way.

Notably, each of the games that I’ve played has taken a different approach to video. Never Alone, a 2014 game that I played in April when it was included with the PlayStation Plus subscription service, uses documentary footage as an in-game reward for advancing through the game. During short videos that are best watched as you play, the Native Alaskans who helped to make Never Alone explain the folklore and culture that inform the game. It’s essentially the same approach that other games would use for cut scenes, but seeing the real faces of real people creates a sense of intimacy and realism that is beyond the reach of animation.

Her Story, one of the most talked-about indie games of the past month, is closer to the moving-pictures equivalent of a text adventure. The player uses a database — the interface resembles a 1990s computer desktop — to comb through snippets of a series of police interrogations. (The first four video clips, provided at the start of the game, come from a search for the word “murder.”) The videos are all quite short, from a few seconds to, rarely, a little more than a minute. Like L.A. Noire — or parts of L.A. Noire — Her Story is a game about watching, listening, thinking, and then deciding. Unlike the interrogation scenes in L.A. Noire, the ones in Her Story are gripping, because the videos convey the emotion of a human actor’s face.

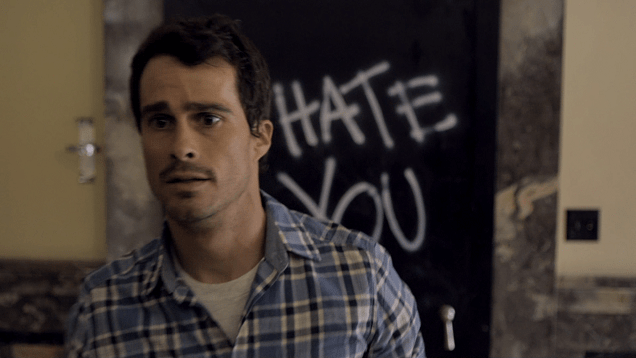

Missing, the game from which I took the screenshot at the top of this page, attempts to weave video and animation together using an approach that is similar to that of a Hollywood movie. It’s a very traditional point-and-click adventure game, except it looks like this:

At least two more games that use video in novel ways are scheduled to be released this year. Guitar Hero Live will include live-action music videos that, its developers say, can shift undetectably between “failing” and “succeeding” based on the player’s performance. Two versions are filmed, one positive, one negative, using robotic cameras that can capture the exact same shots of a band or a crowd.

Nina Freeman’s Cibele, the beginning of which I played at this year’s Game Developers Conference, tells the story of a young woman’s first sexual experience by switching, much more abruptly, between animated interactive sequences and non-interactive video. Video games have rarely been good at handling the subject of sex. Maybe the inventive use of video is a way to change that. Watching two cartoon characters have sex, after all, has rarely done anything but generate audience laughter. (Watching two puppets have sex, granted, gave us one of the greatest scenes in film history.)

Big-budget studios like Rockstar, Naughty Dog and Rocksteady have been moving away from cut scenes that look markedly different from the in-game world and toward interactive and non-interactive sequences that are almost visually indistinguishable. That’s not the only valid approach. The video sequences in Cibele are intended to remind players, Freeman said, that they are playing not as themselves but as “a real girl with a real body.”

In all of these games, the use of video turned me into a little bit more of a watcher and a little bit less of a player. Even in Missing, the player doesn’t really move the protagonist in space, except by clicking on the screen. Computer animation is likely the only way for players to feel like they have real control over an experience, to become co-creators in what Neal Gabler, in his biography of Walt Disney, called “a process of giving life, of literally taking the inanimate and making it animate.”

But video can also do something that animation cannot: capture a specific moment in time, whether an actor’s performance or a documentary subject’s interview, and make it live again. We’ve had cinematography in video games for a very long time. It’s been nice, this year, to see a little more cinema.

Chris Suellentrop is the critic at large for Kotaku and a host of the podcast Shall We Play a Game? Contact him by writing chris@chrissuellentrop.com or find him on Twitter at @suellentrop.

Comments