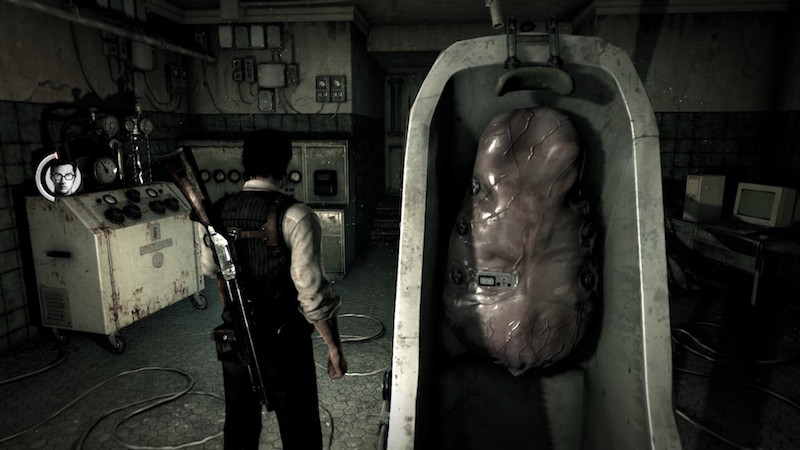

The Evil Within was supposed to be Shinji Mikami’s triumphant return to form. The creator of Resident Evil had revitalized the brand once with RE4, and The Evil Within promised to be the next big step in the survival horror genre. A new universe from the mind behind some of Capcom’s biggest games should have been great, but The Evil Within failed to meet the expectations set by Mikami’s previous work. Even though Mikami set out to make a horror game, what he ultimately created was a game that’s much better at action than at horror.

The premise is simple: Sebastian “Seb” Castellanos, a cop, is called in to investigate a violent homicide at a mental institution. He then gets trapped in a nightmarish hellscape and has to fight his way out by killing Ruvik, the psychic monster determined to kill everyone.

The Evil Within bucks the trend of weaponless horror games like Amnesia and Five Nights at Freddy’s and stocks you with a carefully-balanced arsenal. Instead of charging through waves of enemies, mowing them down with powerful weaponry, The Evil Within cleverly starves the player of resources and randomizes pickups, so no two playthroughs are the same. Some guns can kill enemies in a single shot, but good luck keeping yourself stocked on ammunition.

The Evil Within gets a lot of mileage out of this balance, but it recognises the importance of occasional empowerment. Rather than a single, monotonous sense of dread, The Evil Within is sometimes generous with resources. This generates an ebb and flow of excitement and fear, giving the game a rich emotional texture. One moment, you’re racing through the city on a bus blasting away at the monster the size of a house; the next, you’re creeping through a village, hoping against hope that no one notices you. Mikami wisely recognises the importance of emotional diversity, and his game delivers.

Of course, simply having a beautifully balanced inventory system isn’t enough to make The Evil Within feel great. Fortunately, Mikami delivers some robust weapon feel as well. Shoot a monster in the face and you might end up simply blowing a hole through its skull, but that might not be enough to kill it. If you shoot again, the bullet might actually fly through the hole you made, failing to halt the monster’s advance. Similarly, when you hit a monster with a shotgun, it doesn’t simply absorb the damage like a sponge. Hitting someone with a shotgun in The Evil Within causes them to fly backwards, fall over, or explode in a shower of blood. When a weapon hits in The Evil Within, it hits with conviction.

This intelligent use of great-feeling weapons and the flow of abundance and scarcity are highlighted by excellent encounter design. Some of my favourite encounters in the game are in Chapter 6. At one point, you’re trapped in a locked room, waiting for a friend to pick the locks while monsters storm you from all sides. Shortly after, you have to snipe heavily-defended enemies perched high above you while juggling waves of enemies who’d rather get up close and personal. Other great encounters include sneaking through a village at night, setting enemies on fire before they’re aware of you, the aforementioned bus chase, and a fight with a boss who can become invisible.

At its best, The Evil Within works when it’s presenting its players with new, action-intensive challenges that demand engagement. Facing off against the sniper encounter in Chapter 6 is great because there are so many paths through the level, as well as massive cliffs and enemies who attempt to herd you into areas where you’re more vulnerable. The quality of tension in that moment is radically different from the tension in Chapter 3, where you’re low on weapons, can hear an enemy trapped in a barn nearby, and have to resort to staying out of sight, stabbing enemies in the back of the head and stealthily setting them on fire when you can.

The Evil Within’s strength is in its ability to contrast different kinds of tension; rather than repeating the same things ad nauseum, The Evil Within plays it like variations on a theme. Build great variation around strong mechanics and you’ve got a recipe for the perfect game. The problem is when its attempts at variation go too far, veering into survival horror territory that it can’t quite master.

The Evil Within is a game plagued by as many, if not more, bad encounters than good. One of the worst involves waiting for a specific enemy to get close before the player can run away from him. But if you hide two or three times, you can circumvent this encounter entirely. During one of the encounters, I walked away from my computer, poured myself a glass of water, came back, sat down, and found that the bad guy had left the level, all without my doing anything.

Many great horror games rely on stealth. For instance, Alien: Isolation, one of my favourite horror games, let players hold their breath, use tools to distract enemies, and even move around in the locker they’re hiding in. As a horror trope, The Evil Within’s stealth mechanics never feel up to snuff. Great horror requires tension, not passivity and frustration.

The Evil Within also struggles with player movement. While many horror games seem to rely on bad controls and tanky player movement to generate fear, The Evil Within’s shoddy movement just feels unfair. It seems to be more animation-driven than input-reliant, which means that the character may continue to move after the player has stopped pressing keys. Traps are a common obstacle throughout the game, but players often die due to traps because Seb keeps moving when he shouldn’t. These deaths feel undeserved, especially when coupled with the game’s occasionally strange hitboxes — the invisible box around all objects in games that detects whether objects collide with each other or not.

One section involves a boss that requires split-second timing but could also kill you in one hit. Several of my deaths seemed to be thanks to the game not responding to me as quickly as I would have liked — a must when a boss requires great timing — or because the hitboxes felt ill-defined. Several times, a particularly frustrating boss was able to kill me with a single lunge when I felt she should not have been able to, based on how our player models failed to collide.

Many enemies in the game are invincible, or nearly so. While many horror games have relied on this idea to increase the player’s sense of fear and helplessness, The Evil Within often leaves the player little choice in these encounters except to run around in a circle hoping these enemies won’t hurt you. One particularly egregious encounter locks you in a small rectangular room. Run around the edge of the room, take the occasional shot at the boss, he’ll disappear for a moment, reappear, and proceed to follow you around the room — repeat until a door opens.

It’s not nearly as fun as the more proactive ways the game gives you to deal with enemies, such as setting up traps in a courtyard before letting a madman with a chainsaw loose, or counter-sniping a particularly nasty enemy, switching to a shotgun and blasting a crowd of zombies, seamlessly changing back to your rifle and sniping another enemy, then luring some zombies into a trap, all in one smooth motion.

Good encounter design is dramatic encounter design, meaning it follows the rules for good drama. The player wants something, but something is in the way of obtaining that, so the player must struggle to overcome the obstacle to reach their goal. Simply running around a room to avoid getting hit by an invincible boss isn’t very dramatic. Horror games succeed by trimming the fat; the best ones try to ensure that every element works together to create a whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts. But The Evil Within is so preoccupied with trying to throw every single idea into the game design blender that it never bothers to ask itself whether those ideas work well together.

The result is a messy game that can be great one moment and horrible the next, rather than a tightly focused horror experience. The Evil Within tries to do too many things without taking advantage of its combat strengths, repeating encounters that are built around its horror weaknesses instead. Things that should be frightening come off as weird, comical, or forgettable, like a room full of murder Roombas (yes, that’s a thing) which comes across as more silly than frightening.

Ultimately, The Evil Within betrays the horror genre’s greatest strength: it throws too many ideas at the wall to see what will stick. It tries too hard to avoid being an action game in its encounters, but the action mechanics are vastly superior to the non-action mechanics. Nevertheless, it’s well worth playing; the sheer variety of encounter design is worth exploring, and there are lessons to be learned from both the successes of its action and the failures of its survival horror. The Evil Within isn’t perfect, but it’s always interesting.

GB Burford is a freelance journalist and indie game developer who just can’t get enough of exploring why games work. You can reach him on Twitter at @ForgetAmnesia or on his blog. You can support him and even suggest games to write about over at his Patreon.

Comments

8 responses to “The Evil Within Was Better At Action Than Horror”

My biggest issue with the Evil within was the difficulty curve and that chapter 11 boss. I nearly gave it up completely and once I had finished, I did not want to start it again, because the thought of going through that again was nightmare inducing

“___ is a better action game than a horror game” is applicable for basically every game Shinji Mikami has made. The dude makes third person action games that will occasionally have a horror theme to the story. I just want him to work on more straight up action games … Vanquish was the raddest shit

Vanquish rocked. How fast was that combat. Where’s the sequel already!?

I really enjoyed TEW, flaws and all. Shinji nailed the creepy vibe in that early village chapter. Some of those boss battles though…..Ch7 with the Keeper (safe head). Man that sucked, I attempted that like 50 times priior to beating & progressing.

Got up to the start of Chapter 9 in my Akumu run but got distracted. Chapter 6 was watershed point that I prepped for and breezed through (burning house solved with levelled to buggery flash bolts). Something came up or I got frustrated at the idea of randomly spawning Ruvik in that chapter or the thought of the upcoming mega fight with spider corpse girl in chapter 10. That was hard enough on normal but extra bear traps and insta-death… urgh.

It will be hard to pick up again though as I’ve lost the adjustment period to the janky heavy controls. Akumu is pretty easy in retrospect as it makes the game relatively straight forward to approach; every enemy is the same and just as dangerous regardless of what they are which means you treat everything with the same kit gloves.

LOVE this game! Played it endless, over and over, got all the trophies – so many great memories. Its supposed flaws never bothered me at all. Looked beautiful too.

One of it’s biggest strengths was the combat mechanics – there are numerous ways to approach each encounter.

The one thing that annoye me was the overuse of really played-out horror imagery like clown masks, BDSM torture devices, etc. kinda like how all the Blumhouse/James wan horror films use. Lame.

I really enjoyed The Evil Within, and I feel that this article is a overly critical.

Is it the perfect horror game? Perhaps not, but not every horror game needs to be the epitome of pure horror.