In 2001 Jesse Lacey, the pale poster boy of emo, crooned about mixtapes. Mixtapes, in this case, were artfully-compiled collections of songs stitched together for another person. They were the burned CDs you’d slide in the locker of a crush in high school or the cassette tapes obsessed over in a Nick Hornby novel. These days, mixtapes are somewhat obsolete given digital playlists. But the mixtape format is finding new life in video games.

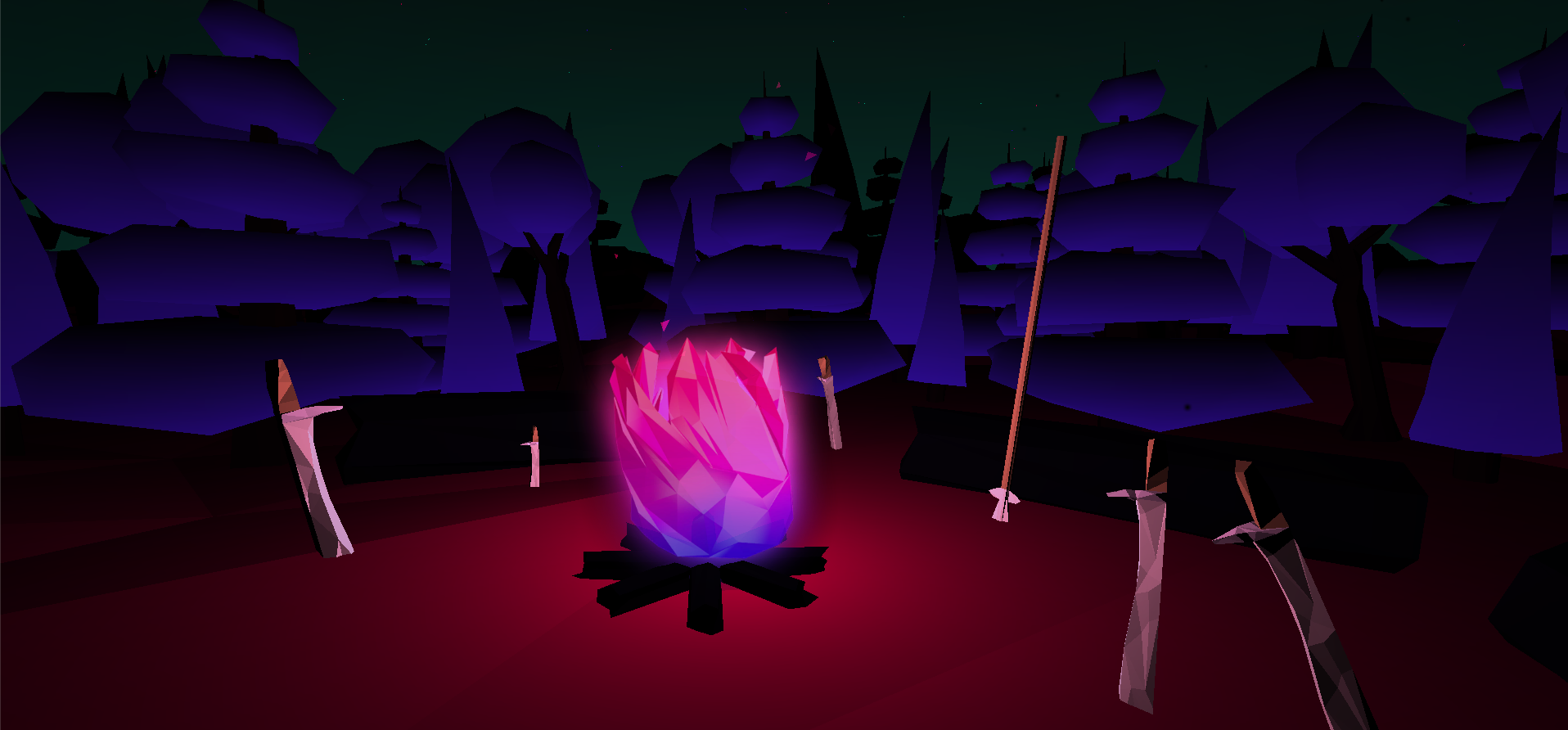

A screenshot of Exit 19, one of the games in Ambient Mixtape 16.

Today’s mixtape-inspired games are different to the minigame-centric titles like the ones in the Mario Party series or the Rhythm Heaven games. Those games feature bite-sized diversions without a unifying thread. These minigames are non-essential and hold little weight on their own.

In video game mixtapes, the unifying theme is essential, just as each song is crucial to the flow of a traditional mixtape. No matter how different each part may be, the segments within a video game mixtape can make even the most varied project feel complete.

Bamboo EP

Take for instance last year’s Ambient Mixtape 16, an ambitious project made by nine developers from all across the world. According to one of the project’s core organisers, ceMelusine (who ended up dropping out of the project later on), the nine micro games appearing in Ambient Mixtape 16 were tethered to the central dusk-tinged theme “after hours”.

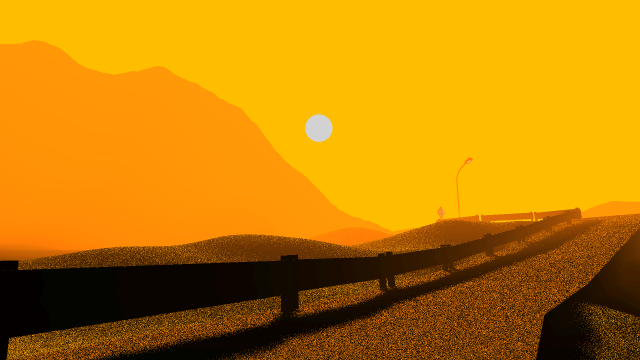

From a lonely orange-hued stroll to an abstract, dimly lit nightmare of a city, one thing that tied the games together, aside from its theme, was that each developer worked from the same First Person Camera Controller originally crafted by the developer Alex Harvey. Despite the differences between each developer’s sensibilities and aesthetics, Ambient Mixtape 16‘s assemblage feels unified like musical mixtapes, beyond the road of embedded minigames originally paved by the WarioWares of yesteryear. The mixtape format, at least for Ambient Mixtape 16, served as a focal point of togetherness between developers.

“It often feels that when you’re doing [game development] that you’re competing with other people, you know, for attention or press or whatever,” ceMelusine told me. “But I think that the mixtape is a really good way to subvert that. To take a whole bunch of people and work and group it together, and be strong as a group, and I think that’s really valuable.”

East Van EP

ceMelusine previously made East Van EP, a game that has been in development for two years with small instalments added over time. Its final addition released recently. Though not labelled as an outright mixtape, instead it bears the title of an “EP”, a common name for short albums. “The EP format struck me as a good way to get people back to my old games that hopefully would be interesting and show artistic growth,” said ceMelusine. The collection is reminiscent of a coming-of-age tale, except as you play through its surreal, David Lynch-inspired blips, you see a developer, well, develop.

Part of ceMelusine’s design philosophy is to make his games accessible to all audiences, just like music. “The music thing is an attempt to make things that are more mood-based and more about being there and experiencing it, because anyone can pick up a record and play it and listen to a song,” he said. “Maybe there’s some skill to listening, but it’s not like you need to have some education in order to do that, and I don’t like that that’s a thing about games. It often feels like you have to have this whole lexicon under your belt before you can really start to see what’s cool about a lot of games.”

Sokpop, an indie game collective based in the Netherlands, know the methodology of music well. They recently released Bamboo EP, a collection of micro games by the collective’s four members (Rubna, Tijmen Tio, Aran Koning and Tom van den Boogaart). “In music you have a song and the song is on a record, and the record is published by a record dealer, [but with] games you don’t have those rules,” Rubna, a member of Sokpop, said. “I thought it was interesting to bring that to games and see what it does.”

Bamboo EP‘s development began when Boogaart showed a rough version of what would become the collection’s level “Bamboo Ball”. The idea of making a game collection centred around bamboo piqued the interest of the entire collective. With little time to work alongside one another on a regular basis, they dreamed up the idea of a video game “EP”, which Tio pointed out literally stands for “extended play” — a fitting pun for a video game bundle.

Each of Bamboo EP‘s three games plays wildly differently, just as a mixtape’s songs might not flow as cohesively as an album’s. But despite ranging from Nidhogg-style sword fights to dodgeball, they all share the common theme of bamboo. Like a love-themed mixtape, Bamboo EP is cobbled together by incessant imagery of the “sturdy, yet flexible plant”.

In making the EP, the members of Sokpop each worked individually on their bamboo-filled micro games, before sewing the games together for the final package. Once a player beats one section of the overall game, they unlock another feature in another segment, something that Tio bills as a unique aspect he hasn’t seen in many mixtape games. Tio credits the collective’s closeness as friends to making the seamlessness between the different games possible.

Whether we call them “extended plays” in video games or resign them to auto-curated playlists on Spotify; whether it’s the incremental updates to East Van EP in cataloguing a developer’s own growth over the years, a game collective paying homage to a beloved plant, or nearly a dozen developers adhering to a singular, mood-saturated concept, the mixtape retains its soul, even if the definitions change. The mixtape has evolved — beyond just music, beyond just play — but the heart and spirit persist.

In author Rob Sheffield’s autobiographical novel Love is a Mix Tape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time, he recounts his relationship with his now-deceased wife through the mixtapes they shared with one another. “Most mixtapes are CDs now, yet people still call them mixtapes,” Sheffield wrote. “The technology changes, but the spirit is the same.” The mixtape-inspired video game bundles of today channel that personally curated spirit that Sheffield speaks of. They won’t die, even if they have shed their once-analogue image. Instead, they will adapt to the times and become something new.

Comments

2 responses to “Video Game Designers Are Creating Their Own Version Of Mixtapes”

Sif, Munchy Monk 2 is a masterpiece that totally stands on its own feet.

Surprised that this article doesn’t mention Anamanaguchi’s Capsule Silence, which has some great songs, and is an interestingly weird game in its own right.