Adapting video games into other media is always a risky proposition, but that didn’t stop producer/showrunner Adi Shankar from personally guaranteeing that his Castlevania cartoon for Netflix would end the streak of game-to-TV terribleness and “be the Western world’s first good video game adaptation”. For all Shankar’s bluster, Castlevania turned out pretty good.

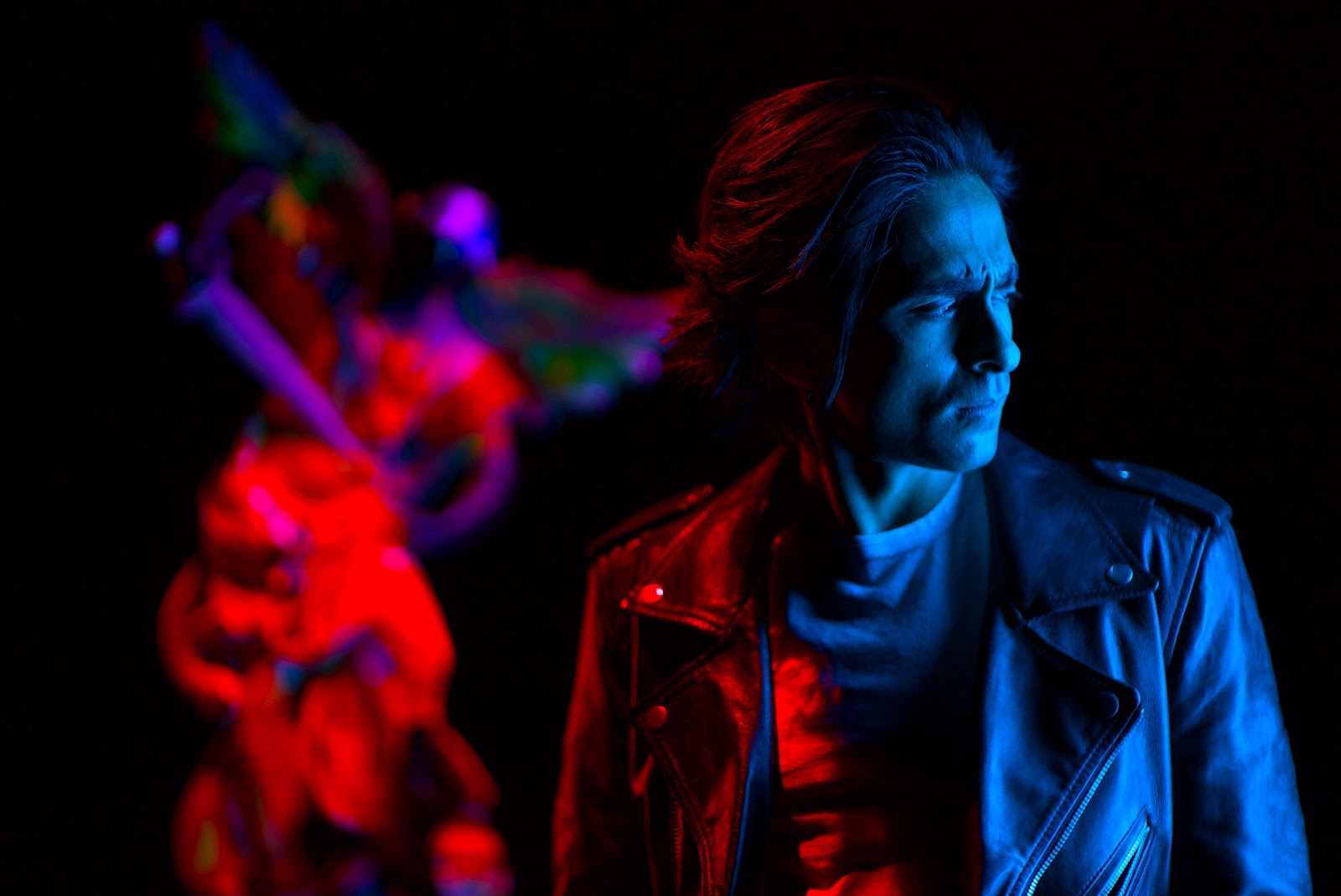

Image: Netflix

So, of course, I wanted to speak with Shankar about how he managed it. Our conversation over the phone last week went into the specific game that provided the framework for the series, the artistic goals he and other creators tried to achieve, and why Dracula is kind of like Magneto.

How did everyone involved break down the story? Was that all something writer Warren Ellis came to you with? Or was it a collaborative effort between the major producing players?

Adi Shankar: The story’s based on Castlevania 3, right? The way I see it, the game provided a really great core blueprint and it’s an issue of connecting the dots and knowing what elements to focus on. Here’s what it comes down to. If you’re a fan of a game, or a world — because they’re not really games, they’re worlds — that has a deep, rich mythology and you’ve really spent a lot of time in it, you start developing a sixth sense about that world. The best comparison I can give is, it’s like a musician who’s covering his or her favourite, iconic song. Right? Once you’ve lived with that song for a long time, like, years — a lifetime — you know what notes you have to hit. You know, straight up, “Yo, I have to hit this note.” And you know what notes you should make your own.

I don’t know if Warren Ellis played the games or not, so — assuming he isn’t as super familiar with the lore of the franchise as some lifelong fans — how did you guys figure out what those notes were?

Shankar: Any good deep story has a great villain, but I believe — and it’s not just me, this has been discussed to death — that a great villain is the hero of his or her own story. This is why Magneto is so dope. Do you remember Secret Wars?

The Marvel comic by Jim Shooter? Yes.

Shankar: Yeah! Remember how dope it was when Magneto was with the good guys, and “Why’s he here?!” and they’re like, “Well, because he’s the hero for his own people!” You’re like, “Ohhh, dude, that’s amazing!” The corny thing to do would have been to throw him in the room with Doctor Doom and Red Skull. But you could also argue that Doctor Doom is the hero of his own thing, too. The only real, like, arsehole, is Red Skull.

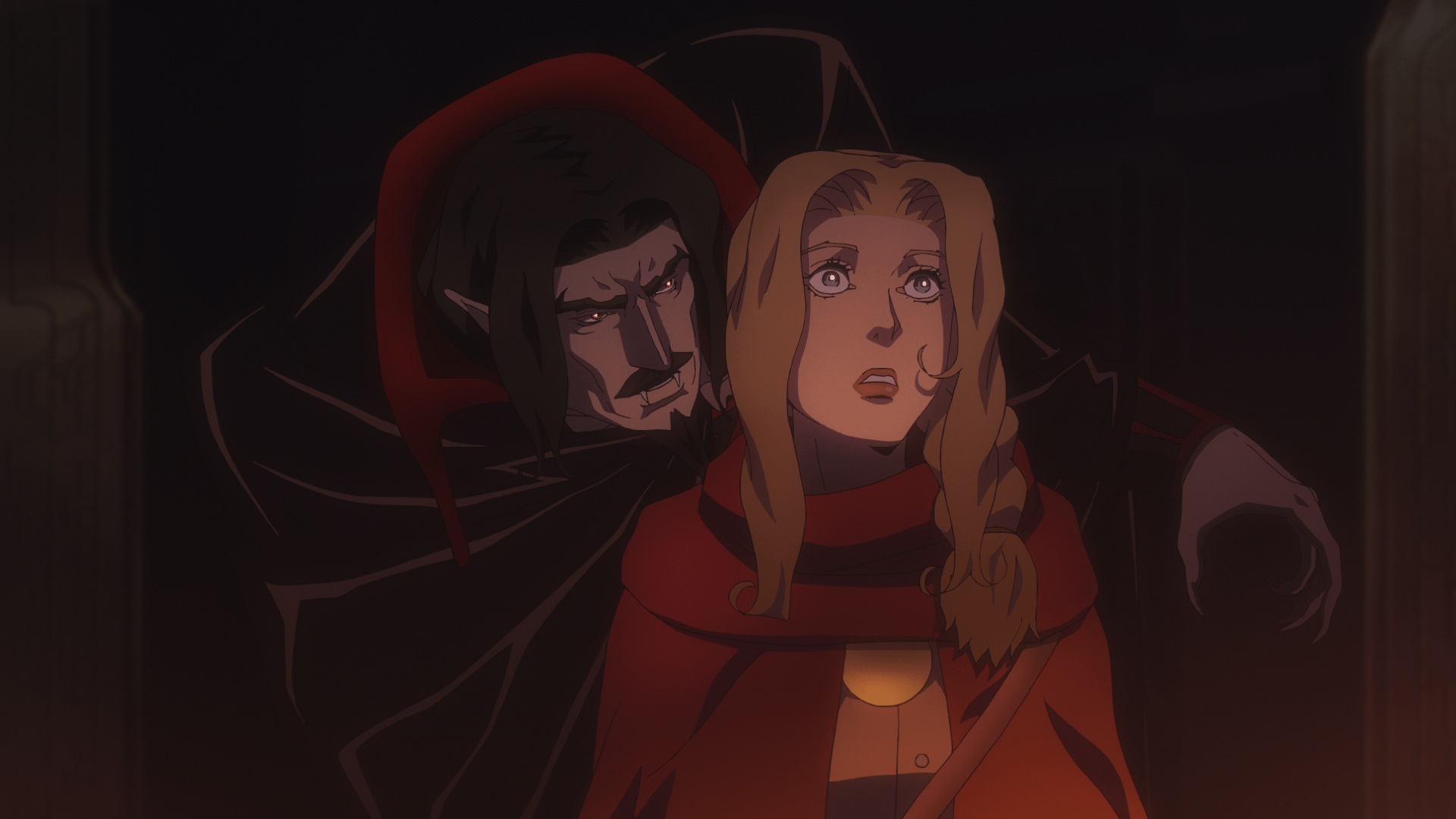

Sorry, I digress. In keeping with that idea, Dracula has to really be fleshed out here, you know? What makes Dracula so interesting as a character is, he’s what you get when immortality intersects with suffering, it instantaneously makes that character profound, because… the lack of meaning of time, creates this paradox for meaning in general, in the context of that character’s life.

Right. He’d been sitting there for decades, maybe even centuries in this castle by himself. Until Lisa shows up.

Shankar: He’s not a “muahahaha” villain, he’s a dude with access to a lot of knowledge. Like, he is a database of knowledge that’s just straight up been forgotten through the centuries, [that he’s been] able to collect because he’s been alive for so long. I think that makes him an interesting character.

You’re talking about villains, and for these four introductory episodes, the church is the villain — something that was not in the games. Talk to me about that choice.

Shankar: Did you feel like the church were the villains?

In the show? Yeah.

Shankar: Interesting. I totally disagree. It’s not the church who are the villains, it was certain people using the church. It’s not like this evil corporation hell-bent on taking over the planet…

It’s one arsehole with access to power.

Shankar: Exactly. This show has to operate in shades of grey, otherwise you get these two-dimensional characters. Two-dimensional heroes. Two-dimensional villains. Two-dimensional everything. Because the true monsters here aren’t the night creatures. The true monsters here aren’t Dracula or the Cyclops, or literally any of the “monsters”. All the horrific actions that happen in the show — and yeah, there’s a lot of bad shit that happens — as a byproduct of the true monster, and the true monster of the show, I would argue, is widespread misinformation and the endless thirst for absolute power.

I get that. It’s in the Bishop’s best interest to keep people dumb and uninformed. Keep them in smaller, narrower worldviews, so he can manipulate them.

Shankar: Right! And the church is just a tool for him to achieve that.

How does the Bishop — a flawed human being with access to this powerful reservoir of sentiment — contrast with Dracula? On one hand, Dracula is the ultimate evil, because he unleashes the horror of the Night Hordes. But on the other hand, he’s suffered great loss at the hands of humanity because of manipulated ignorance. Where does he fall in the spectrum for you?

Shankar: This is a dude who fundamentally doesn’t look at humanity as humane. “You guys are fucking inhumane, you guys are arseholes! Look at what you are doing to each other and the planet at large.” He’s not going, “Oh, yeah, hmm. Maybe I should take it kind of easy.” He’s looking at humanity as a virus. This is an immoral god, effectively going, “You guys shouldn’t exist. You’re a problem.”

Dracula’s son Alucard clearly operates differently because he wants to stop his father. Is there an explanation for him feeling differently about humanity, other than it’s what his mum would have wanted? Has he possibly spent time around humanity to feel like they’re worth saving?

Shankar: A-ha! You have to see season two, my man.

Did you guys have any kind of inspirational guidelines that drove the action? Because I felt the choreography was great. The swordfight in episode four was amazing. How much of that was you having a clear goal in mind vs. making it up as you go along?

Shankar: Nobody on this show operates like we’re making things up as we go along. There’s always a plan. The goal with the whole show was to approach everything as cinematically as possible. What I was trying to avoid from moment one — even in the storyboarding phase — was the traditional, TV style, where it’s just master, medium-close-up, close-up. I wanted to really introduce camera movement. To introduce specific shot design in each scene that not just helps accentuate, but also tells the story visually, without any dialogue. So I think that kind of storytelling becomes the most noticeable during an action scene, but it’s there through the whole show.

There was the opening of episode two where you see the demons lurking on the rooftops and one of them has a baby in its mouth — and you don’t zoom in on it, it just kind of walks by. But it’s still unmistakable what it is.

Shankar: Right. In episode one, once the Night Creatures get unleashed, just to capture the pandemonium, there are so many shots where three layers of things are happening. There’s glass breaking in the background, some guy runs to the right in the foreground, gets decapitated — as he’s getting decapitated someone in the middle is barely escaping and gets caught, too.

And that kind of composition was intentional, is what you’re telling me?

Shankar: It was more than intentional. That was one of the most important aspects of the show. Because, I guess, for me personally, that’s something that has been lobotomised out of movies. Movies are shot more like TV shows, now; it’s safer that way. When you have explicit shot design in a frame, there’s no editing around it. One of the things I think that made Power Rangers really great is yeah, it had a cool story, it had a cool hook, but Joseph Khan is a very old-school filmmaker in that regard. He’s a shot design guy.

On that subject, what was your favourite shot/sequence of the season?

Shankar: The ones I’m going to pick right now are certain moments where Trevor was becoming Trevor Belmont, not Trevor the alcoholic. There’s two of them. There’s the moment in episode two where he rescues the elder Speaker and then there’s that real, final moment when he finally lets the people know, “Hey — you’re not going to kill any Speakers today. Because I’m Trevor Belmont.”

Those are scenes where all the components work seamlessly together. You take these amazing voice actors who brought these characters to life. You take the specific shot design, the intricate 2D hand-drawn animation, you take just Warren’s skill as a writer, as a satirist. You take all these elements, [with] Trevor Morrison’s score — and they come together and work together to make this show what it is.

Comments

2 responses to “Castlevania’s Adi Shankar On How Adapting A Video Game For TV Is Like ‘Covering An Iconic Song’”

Am I the only person that thought that this show wasn’t that great? I mean, sure, the Dracula parts were amazing. But, everything else just wasn’t Castlevania.

“And that kind of composition was intentional, is what you’re telling me?”

It would have to be, wouldn’t it? This isn’t pointing a camera at people and recognizing opportunities from multiple takes. It’s literally designing everything from a blank piece of paper to the end result.