Vampyr is a brilliant roleplaying game married to a mediocre action game, and their contentious relationship turns what could be a good time into a memorable but uncomfortable experience.

Vampyr is a new action RPG by Dontnod, the studio behind 2013’s cyberpunk adventure Remember Me and 2015’s narrative game Life is Strange.

You play as Dr Jonathan Reid, a World War I surgeon specialising in blood transfusions. In 1918, Reid returns from the front to London to discover he’s been turned into a vampire by a mysterious and powerful progenitor.

The Spanish Flu pandemic is raging, and Reid is torn between caring for the city’s citizens and using them to sate his new bloodlust. He becomes embroiled in conflicts between England’s vampire elite, secret societies of monster hunters, and supernatural forces.

Despite the RPG elements, you can’t customise Reid; you’re stuck with his lumberjack beard and sonorous voice for the duration of the game. This is fitting – Reid is a distinctive character I found both exciting and difficult to inhabit.

Through the game he converses about hot topics of the day, such as women’s rights, recent medical phenomena such as Cotard’s syndrome and the placebo effect, and the emotional impact the war has had on the people around him.

As a vampire, he can’t enter people’s homes uninvited, but he isn’t above drawing on his authority and trustworthiness as a doctor to get what he wants. Reid is a complex character with tough conflicts to wrestle with.

Gameplay-wise, Vampyr is as conflicted as its protagonist. It’s several different games in one: An action RPG with levelling up and combat, a partly open-world exploration game, and a dialogue-based game about relationships.

The most interesting part is the social side. The game is populated with unique computer-controlled characters, each with a name, backstory and health status. As you explore a neighbourhood and chat with the locals, you learn more about them. You activate sidequests and new dialogue options, and you discover relationships, intrigue and personalities.

Vampyr‘s human world feels like a British period drama. Doctors at the hospital argue and undercut each other; a woman lives in a homeless shelter because she lost her job as a result of union activism; a couple keeps their relationship secret for fear of societal judgement; a friendly merchant just wants to find a good place to eat.

I delighted in running around learning everyone’s gossip and dramatically demanding answers. I also felt a responsibility to these people, crafting medicine to treat them when they got sick. Doing so is one of the ways to improve a district’s overall health. Let an area’s health fall too low and it will be overrun by illness and monsters, taking your friends along with it.

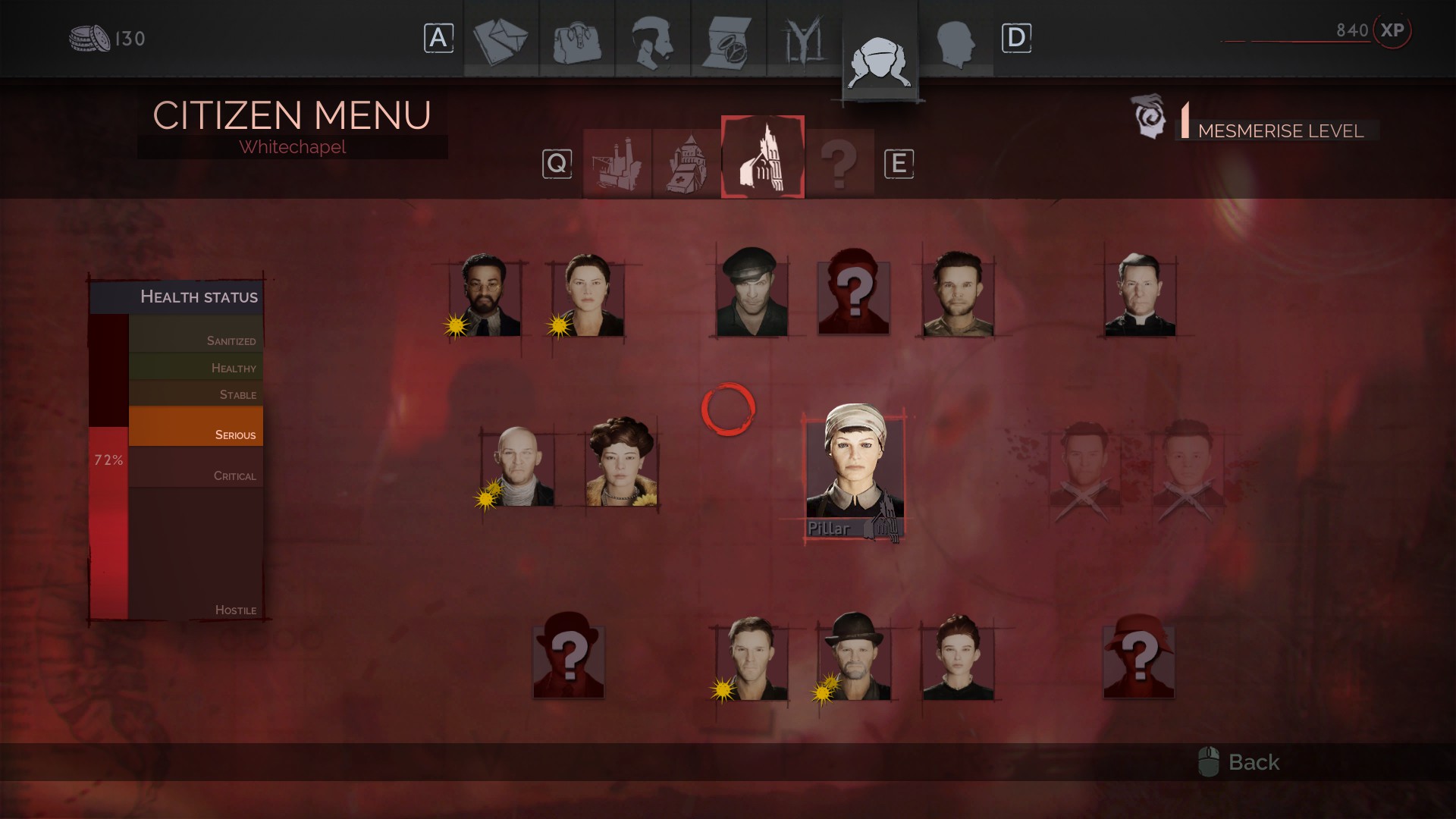

The citizen menu, showing the people who live in an area and what its status is.

Of course, you don’t just treat non-player characters’ health out of the goodness of your heart. Healthy NPCs have healthier blood, represented by how much XP you gain if you decide to feast on them. Getting to know a character unlocks even more XP, meaning the most fruitful people to bite are the ones you’ve talked to and cared for the most.

I didn’t expect this to be as morally difficult as it was, but Vampyr‘s clever use of interlocking relationships and medical practice made realising I’d need to feed on an NPC harrowing.

Few NPCs actually look you in the eye during dialogue. It’s unsettling but I got used to it pretty quickly.

Despite characters’ wooden animations and unnerving lack of eye contact, each of Vampyr‘s NPCs are so interesting it’s hard to see them as dinner. At the start of the game I ate a couple of lowlifes, luring them into the shadows and chowing down before I got to know them. Later in the game, desperate for XP, I decided I’d eat a lonely drunk in a bar I’d met at the start of the game.

But because I’d been around the neighbourhood, I’d opened new dialogue options that revealed a relatable and tragic past. I kept clicking through, and with each new revelation I cringed as I realised I couldn’t possibly eat him.

I wandered the city forlornly looking for someone I could stand to bite, passing over familiar faces until I eventually settled on a woman I thought no one would miss. I found myself apologising to her out loud, feeling monstrous as I watched my XP rise.

You need that XP to level up Reid and gain new vampire powers for the game’s lacklustre, frustratingly plentiful combat. You use XP to increase your stamina, health, and how much blood you have. Blood is the mana for your vampire powers – you can disable enemies’ defences, slash them with ethereal claws, or attack them with bloody tendrils from afar.

You can only level up in hideouts, where you can also craft serums and upgrade your weapons. You do so in lovely menus full of satisfying button presses and sound effects. Everything about levelling up is great – except the actual fighting these powers and menus are for.

Combat ranges from boring to tormenting. The animations are same-y and dissatisfying; in most cases I button-mashed at an enemy until I stunned them, drank their blood, unleashed a vampire power, then repeated until they fell.

You have a few different weapons you can equip in your main or off-hand, some of which have special abilities, but I stuck with one that did high damage and just kept upgrading it to do more, rarely feeling the need to switch.

Fighting forgettable groups of enemies as I traversed the streets wasn’t engaging, but it wasn’t all that bad. Brief flurries of combat were good enough to lighten the burden of wandering the dark, repetitive map. It’s cluttered with needlessly locked doors and devoid of fast travel, requiring plenty of dead ends and backtracking that fights made a little more lively.

But then there are boss battles, which come at peak narrative moments. The first one I encountered was tough but not too bad, but later ones as the plot ramps up were clunky and too long.

A mid-game boss – in a pattern that repeats depressingly throughout the boss fights – released dispensable one-hit minions in addition to their easily telegraphed attacks. The game’s targeting struggles to encompass multiple foes. I’d whittle down a boss’ health only to be sideswiped by these fragile enemies because the game fumbled to target them. It was boring and maddening in equal measure.

These unavoidable fights are all joyless slogs of swinging camera angles and unengaging rituals of darting toward bosses, getting a few hits in, and swooping out again. They’re all in purpose of Vampyr‘s grand supernatural plot, and neither that story nor its combat was nearly as engaging as interacting with London’s citizens.

At one point, about to face several dull minibosses leading up to what I knew would be another insufferable boss battle, I veered from the plot to check on the status of each of my districts.

I realised Whitechapel was falling into critical territory. Many characters whose minor illnesses I had ignored had gotten much sicker since I’d last visited. Instead of getting the forthcoming combat out of the way, I crafted some medicine for headaches, bronchitis and sepsis, then ran all the way back to Whitechapel.

I spent an hour wandering the streets doling out treatment to NPCs. I learned more about two characters’ relationship and undertook a fetch quest for them with a tough twist.

On the one hand, I didn’t visit Whitechapel much any more. Losing the area wouldn’t have mattered to my ultimate progress through the game. On the other hand, Reid is a doctor, and I shared his sense of duty to the people we’d grown so close to.

The time I spent roleplaying as an everyday doctor, putting the game’s inevitable violence behind me to do something good despite my ultimate goal, was my most compelling experience with Vampyr. It’s one that wouldn’t have happened at all if I hadn’t been avoiding the combat the game ultimately chooses to focus on.

I’ve played about 20 hours of the game, much of it spent exploring and talking, and I get the sense I’m about two-thirds through the main plot. Players less turned off by the combat or less interested in sidequests might progress through it faster; the developers say the game is 15-30 hours.

Despite my occasional frustration, I’m excited to see the game through and to get answers to its big mysteries, even if they don’t interest me as much as the human side of things.

Vampyr is a lovable mess. Its lack of visual and technical polish and its unpleasant combat are offset by excellent characters and dialogue that I longed to be its real core. I just wish its disparate pieces were more in sync.

Comments

8 responses to “Vampyr Would Be Great If Not For The Combat”

Agreed that the combat is lacking in polish, the lock on system and hit boxes are sometimes frustrating but I have begun to expect that though with 3rd person CQC games.

I eventually settled on a woman I thought no one would miss.

If your talking about the woman that I think you are then Shame on you.

Pretty sure she has a child, which is why she chooses/is relegated to doing the job she does.

I actually enjoy the combat. It isn’t as deep as some other games but the stress of combat is a nice incentive for eating people to get more powerful which creates the moral dilemmas that make the game great.

Remember Me (same developers) had combat that was criticised by most press, but I didn’t mind it, and the memory rewind sequences made it so worthwhile. This looks to have similarly interesting things to make up for the combat, so I’m looking forward to it.

Yeah I felt Remember Me was unfairly panned and it seems like Vampyr is getting a similar treatment. I think their games aren’t going to be for everyone but they always nail the atmosphere and story and that goes a long way in my book. The constant utilitarian calculations you are making in Vampyr add so much to the feeling you are a Vamp going against it’s own nature. I’m loving it so far.

The combat is the deal breaker for me. Sounds lacking…

Like the Batman games or assassins creed where you just mash buttons. Fuck that

Fair bit more complicated than Batman. Less focused on combos as a response to counter prompts, more on selecting which type of attack you use for the enemy, whether your attacks have sufficient fuel, AND the enemy’s current status eg: stun bar level, how many times you’ve stunned them for getting in a quick attack then feeding on, how much aggravated damage they’ve received that they won’t regenerate vs how much regenerateable damage they’ve received. Numerous types of enemy in a group (even amongst the more boring humans, let alone the beasts and shadow-clone/teleporting vampires), all potentially dealing different types of damage. Throw in more stuff like parry mechanics for 2Hers, shield/root/ranged pierce/stealth abilities and it all starts getting significantly more complicated and nuanced than I ever found Batman’s combat.

Give how freely the author of the article appears to have noshed on innocent civilians for the sake of boosting their exp, I strongly suspect they just out-levelled and overpowered everything. Playing as a ‘Good’ vampire means playing hard mode, and all the mechanics ignored by OP button-mashing start to actually matter.

Sadly, this increase in complexity appears to come with a few shortcuts to polish, where Batman wins out. Some enemy ‘lunge’ attacks have collision detection well past their animation, leaving the animation to streeeetch past what it appeared it would do, just to catch you because you were inside the invisible zone and didn’t dodge/parry. It’s a minor annoyance and if it kills you, you quickly learn, but it feels cheap.

Interesting. The RPS review praised the combat as being one of the best aspects of the game while calling out the RPG aspects and dialogue as being… inconsistent.

I picked it up but haven’t had a chance to play it yet, still really looking forward to it, always interesting when critics are split on stuff like this.

Considering the size of the development team and budget they had this is a very good game in the vampire genre… these guys did a good job, there is issues in the game but hell i can easily ignore it because the game it’s self is good

combat is truly awful, bosses are indeed maddeningly frustrating and dull with loads of health

I’m really starting to enjoy the combat in Vampyr, partly because I haven’t levelled up more than the two mandatory nights’ sleep you need to open up the map and advance the story, while trying to explore every available inch of the map to ensure I rescue/heal every NPC possible and don’t miss any by advancing time.

It’s getting pretty rough out there taking on level 16+ creatures that can one or two-shot you, but it’s teaching me a lot about how the game handles collision detection, move-telgraphing/interruption, and stamina/health/blood management. I now know exactly which areas I need to level up in the next time I’m forced to take a nap and advance the timeline, and I’m looking forward to the increased effectiveness that will bring.

Sure, if you actually eat people like some kind of fucking monster, and risk everyone’s health by daring to sleep before you’ve hunted everyone down and cured their diseases, you’ll probably be ABLE to button-mash… but try doing that with something twelve levels higher than you and you’ll find yourself staring at that long-ass post-death load screen for the next ten minutes.

Bought it this week, not impressed at all.

– Combat sucks. The interesting abilities are gated behind a blood (i.e. mana) gauge that you have to manually refill, which means you’re mostly flailing at people with a wooden stick so you can make them woozy enough to refill it.

– Really bad design choices. No manual saves., no fast travel, you lose ammo, blood and consumables if you lose a fight but the enemies respawn, quests don’t have a recommended level so it’s easy to wander into one that’s way beyond your level. It’s like they tried to make it as frustrating as possible.

– The story and gameplay are at cross purposes. You fight hundreds of human enemies and no one cares, but the moment you drain someone out of combat you’re an inhuman monster. It’s also never explained why you can’t drain someone non-fatally, or why vampires can’t just live off animal blood (the main character can drink rat blood, for instance). Maybe it is further in the story?

– There’s no engagement for “Good” players. If you’re not interested in eating innocent people, most of the game becomes a massive grind.

– There are way too many named NPCs, all of whom seem to have their own stupid problems that only the player can solve. Find my wallet. Bring me this letter. I stopped caring after the first dozen.

– You can only level up by advancing time, but advancing time will respawn enemies and make people sick, both grinding activities you have to deal with before you can get to something interesting.

I’m not very far into the story but it just seems to be the usual generic “sad vampire” story we’ve seen a hundred times. I don’t recommend picking this up.