In the 1980s, Marvel Comics editor Denny O’Neil had a problem: superstar writer Frank Miller was leaving Daredevil, the book he turned into a runaway sales hit.

O’Neil had to find someone to write the book after Miller’s red-hot run. Ultimately, he started scripting the Man Without Fear’s book himself, turning out my favourite run on Marvel’s blind superhero.

The idea of Daredevil that most fans enjoy in 2018 comes in large part from Miller’s work on the character. Picking up on the tonal shift initiated by writer Roger McKenzie, Miller’s scripts and art re-invigorated Daredevil with heavy doses of pulp and melodrama.

Miller’s moodier approach was influenced by Mickey Spillane and Japanese manga like Lone Wolf and Cub by Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima. The combo of hard-boiled crime, simmering sexual tension, and creepy ninja cults bumped Daredevil up from the publisher’s C-list until Miller left.

As the editor on Daredevil, O’Neil faced a unique challenge becoming the title’s writer. He knew what made the book work but couldn’t just parrot the brass-knuckles stylings and Japanese influences.

He found his own path, just like he did on Batman—over the course of his decades-long career, he spent time as both writer and editor at DC Comics, helping steer the Dark Knight’s publishing history into crucially important stories and modalities.

O’Neil started writing Daredevil in 1983 with issue #194, three issues after Miller left. You could make a case that the early arcs in O’Neil’s tenure draft off Miller a little: teaming up Daredevil with Wolverine, taking him to Japan, and culminating with a brutal blood-feud fight with Bullseye.

But O’Neil was a longtime veteran who’d done monthly comics for about two decades at that point. His choices turned the focus of the series more inward, giving readers a Matt Murdock who struggled through the contradictions of his double life.

The series’ main character was a rich, high-profile attorney who also prowled New York’s grimiest locales as a vigilante, skirting the law to mete out justice. He lived in a moral grey area and O’Neil showed us how hard that all was.

The first major antagonist O’Neil created for the book is an example of his ambitions. Micah Synn was the leader of a tribe descended from a group of English colonizers who got lost in Africa.

The main thematics of the Synn storyline centered on an “urban jungle,” but were interpolated with great little grace notes built around media manipulation and moral relativism.

The 1980s yuppie obsession with status seethes through these comics, too, largely through Foggy Nelson’s wife Debbie. When she throws a party for Synn and the Kingorge tribe, she finds out uncomfortable truths about both herself and her guest of honour.

Daredevil shows up to stop an assassin from killing Synn, which leads to a fucked-up inversion of a team-up with Iron Man that happens after a drunk Tony Stark crashes the party. (O’Neil was also writing Iron Man at the time and had James ‘Rhodey’ Rhodes in the armour while Tony struggled with alcoholism.)

Later, in Daredevil #206, crimelord Wilson Fisk warily considers recruiting Synn but has some concerns about his behaviour.

Alpha-male that he is, Synn doesn’t listen to the Kingpin and forces himself on a conflicted Debbie. He then goes on to terrorize Matt Murdock after figuring out he and Daredevil are the same person.

As the thuggish chieftain and the Man Without Fear fight in the middle of a snowstorm, the skirmish gets unexpectedly interrupted.

This beat with Fisk is great because it builds on Miller’s work with him, reinforcing the idea that he’s a devoted husband despite also being the murdering Kingpin of Crime.

Ultimately, Daredevil doesn’t beat Micah Synn. The excesses of modern life in New York City do that. That resolution and other similar plot beats made this Daredevil run feel mature in a way that wasn’t shallow.

When I first read these stories, somehow I knew they were being written by someone who knew what it was like to go through a bad break-up, be depressed, and struggle to be your best self.

As artifacts of the mid-1980s, these comics lean on some tropes that are rough to encounter in 2018, particularly in some female characters. But, by and large, this run feels like O’Neil is revisiting and complicating the genres he grew up on as a boy.

Micah Synn exists as a dark, Darwinist riff on the Tarzan idea. The cowboy story in #215 is a beautiful exercise in form and tone. The main heroes are still both white, yes, but “Ceremony” also makes a point of showing that Native Americans getting screwed by white settlers is a centuries-old practice.

The espionage, corporate, and street-level crimes all feel personal in painful ways. These struggles are as much about saving souls as they are about saving lives.

Tragedy was a mainstay in Daredevil long before O’Neil’s run, but the texture of the tragedy changed during his tenure. The most haunting development happens in Daredevil #220 when O’Neil has one-time girlfriend Heather Glenn briefly re-enter Matt’s life.

Faced with a part of his past he moved on from, Matt is cold and guarded. He ignores Heather’s calls…

…until it’s too late: Heather winds up taking her own life because of untreated depression.

Matt beats himself up because…that’s what he does.

Then Daredevil beats other people up because that too is what he does. But, while Matt stops bad guys who take advantage of Heather’s death, the crimefighting underscores the idea that being Daredevil is an unhealthy escape from things he doesn’t want to pay attention to in his everyday life.

The O’Neil Daredevil is also the exemplar of a certain workaday approach to cranking out corporate cape comics in the mid-to-late Bronze Age. The bottom line was that there had to be an issue out each month. Each one had to have a villain, a few fights, character dynamics, and subplots setting up future storylines.

Yet, even the formulaic stuff has a texture and personality that serve as proof that O’Neil was aiming for something more than a disposable entertainment. He has a wonderful ear for dialect, which comes in part from his days as an old-school newspaperman.

The Irish, Russian, and Italian villains are all written broadly, clearly influenced by the pulps and serials the author grew up on.

But you can tell that O’Neil is having fun making their speech patterns and mannerisms different than Matt and Foggy’s. There’s verve and rhythm in the scripting.

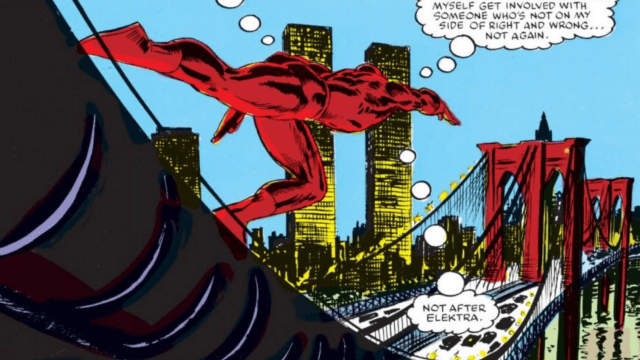

In the midst of all the gloom and depression, O’Neil’s Daredevil communicated the thrill of living in New York like few other comics have.

He used the conceit of Matt’s hyper-senses to write about the rhythmic charms of the city, as well as its seedy pitfalls.

O’Neil had great artistic partners on his run; Luke McDonnell, William Johnson, and David Mazzucchelli all infused humour, melodrama, and zest into the proceedings.

Toward the end of it all, it’s likely that O’Neil was probably putting Matt Murdock through hell to set the table for Miller’s return.

Miller did a fill-in and co-wrote an issue. But there’s no shying away from the fact that O’Neil writes Matt as a bit of a self-involved arsehole, wallowing in his own pain and neglecting to offer attention or empathy to others in his life.

This Daredevil is flawed, human, and often heartbroken. He’s a superhero embodiment of the Catholic beliefs that I grew up with: We’re all sinners at birth, but should try to be better than our own flawed natures.

My favourite issue of Daredevil from this run is #223, a crossover with the Secret Wars II event, something that should’ve been a throwaway fill-in.

In it, the nigh-omnipotent Beyonder gives Matt his sight back as a retainer payment for research into possible legal methods to take over the world.

But that puts Matt on the horns of an ethical dilemma that he can’t abide by.

O’Neil’s run codified what we now understand as the canonical Daredevil personality. One could argue that Matt Murdock is kind of a dry alcoholic. He’s self-destructive and impulsive to a fault, yet beautifully attuned to the world—and New York City, specifically—through his senses.

He’s in touch with reality much more intimately than most superheroes, but he’s blind to his own foibles.

Most of O’Neil’s Daredevil work hasn’t been reprinted, but you can find some of it in the Love’s Labours Lost trade paperback.

Comments