Kieron Gillen will never forget the time that he was a female Soviet air bomber in WWII and an aeroplane turned his character into “soup.”

Gillen was playing in Night Witches, an “intensely serious” tabletop RPG about Soviet women air bombers in World War II. His character, a surly type who had escaped Leningrad, landed her plane when another character crashed behind her. She got out to look just as a third player rolled a die to determine their plane’s landing.

“The roll meant that, ‘oh, that means that plane kind of just goes through your character,’” Gillen told Kotaku. “It got quite a big laugh, and I found it quite upsetting in terms of, this is not the end I’d hoped for, for this character. But no, no, she was just turned into soup and random bits of kebab meat.”

Gillen’s latest creative work, a comic called DIE that debuted last month, is a comic about a tabletop RPG game gone bad, and it owes a lot to experiences like that one.

Gillen’s character didn’t get what they hoped for, but at least it made for a good story. And also, a lot of pain.

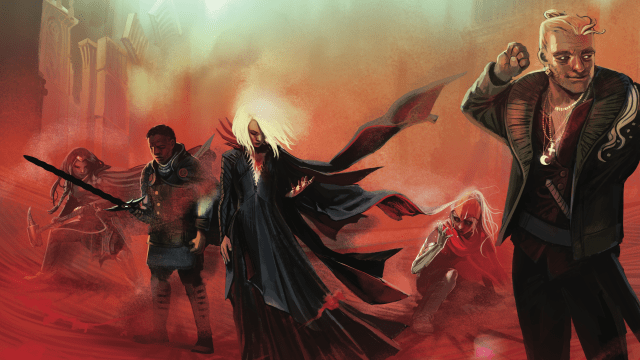

DIE is thrillingly bleak. In it, six teenagers disappear for two years in the early 90s. When they come back, they can’t say what’s happened to them. Twenty-five years later, they discover that the game isn’t over. Gillen has described it jokingly as “goth Jumanji,” if you want a bit of a hint at what happened to this party.

If you really want to get up close and personal with this system, he’s currently playtesting DIE as a tabletop RPG that you can eventually buy and play for yourself.

The first issue of the comic, written by Gillen and illustrated by Stephanie Hans, takes you through that premise. Hans draws the characters in bold, dark colours, their faces contorted into rictuses of grief and pain. The premise is interesting enough, but Gillen’s sharp writing grounds it in the horror of these characters’ lives.

They fundamentally changed as people because of that tabletop game they played when they were 16. The last thing they want to do is go back there—but they have to, both emotionally and bodily.

“One of the interesting things about RPGs is when control is taken away from the room,” Gillen said. “The idea that it isn’t just you, and isn’t just anyone in the room—there’s a friction there, and a lot of pen and paper RPGs exist on that friction.”

At its heart, DIE is about the moment when a woman turns into kebab meat because of an unlucky dice roll. Its characters aren’t in control of the story, but at its whims, and they have to try to work within its systems to survive.

Imaginary Places

To those in the video game world, Kieron Gillen is probably best known as the games journo who co-founded the website Rock Paper Shotgun in 2007. Speaking with Kotaku last month, Gillen said he hasn’t played a big video game for more than four hours since 2013.

It’s at first astounding to hear that from the author of “The New Games Journalism,” the influential essay that shaped what games journalism would become after he left the scene. His call for the form to become “travel journalism to imaginary places” was, at the time, a revolutionary concept for writers who had approached their work as more of a buyers’ guide than criticism.

As of late, he’s largely traded in his controllers for pen, paper, and dice. It’s partly due, he said, to an unpleasant association between games and the death of his father in 2013 (“I spent a lot of time playing video games whilst waiting for my dad to die,” he said), and the fact that he’s just busier these days and video games are “demanding partners” that require a lot of solo time.

“The advantage of tabletop games for me,” he said, “is the fact that I can do multiple things at once. I can get together with my friends. I can scratch the ludic itch, and do something like that in the context of friends. And I can drink.”

Gillen’s busy schedule also drew him away from journalism and towards comics, he said. “I didn’t really have any time to read books. The idea that I could have a bath for an hour, and read a complete trade in an hour kind of fit my life perfectly, and that was one of the major reasons why I did it.”

His work includes an acclaimed run on Marvel’s Young Avengers and the original The Wicked and the Divine with his longtime collaborator Jamie McKelvie.

He doesn’t find writing creatively to be all that different from being a critic. “I used to find journalism is writing about something, while fiction is literally writing about nothing,” he said. “In practice, I don’t believe that for actually a second.”

Although most of Gillen’s work is original, he used his Darth Vader comic as an example of how his critical approach affects how he writes about things. In order to properly write that comic, he had to take apart the larger story of Star Wars, like a critic would.

“You’ve got to synthesise the prequels, which quite a lot of people don’t like, but are also quite an important part of the story. So how can you serve both? In this period, what’s important?” he said. “Darth Vader realises he has a kid. That’s a huge beat. And at the start of it, Darth Vader is the sole survivor of the Death Star, and the Death Star was something that took 20 years to put together. So it was a huge military disaster, and he’s basically the only dude left, so he would be in trouble. At the start of Empire, however, he’s like the boss, he’s much more powerful than he ever was in A New Hope. So something must have happened.”

A Conversation With A Machine

Working on DIE is yet another departure from Gillen’s regular mode of work, so his process had to change to suit it. Often, he makes a playlist of songs he listens to in order to get in the mood for his work, and sometimes he shares them with fans, as he did for The Wicked and The Divine. As tabletop games are a collaborative medium, Gillen wanted to make that process a little bit less deliberate, and decided to let Spotify’s algorithm do some of the song selecting for him.

This process started one day as he was walking home and listening to music on shuffle, and stumbled upon the track “Cherrylee” by the band Gowns. The randomness of finding that song appealed to him.

“Because DIE is about RPGs and mechanics,” he continued, “I was like, ‘I’m just gonna get the algorithm to do it.’ So, I put on ‘Cherrylee’ and then immediately what it selected to hear for me next, and I was like, ‘does this add to the playlist or not?’”

Chancing upon “Cherrylee” is what started it all, though. “It’s a song where the first two minutes are just fuzz, and then eventually a melody comes out,” he said.

“I was like, emotionally speaking, this buzzy emotional sad mess is kind of what DIE is like.”

Comments