This was supposed to be Japan’s year. The Olympics were to be held in Tokyo, and the whole world was going to turn its eyes to Japan. Things didn’t work out that way. The anime Japan Sinks feels like a reminder of that fact.

Note: This review contains spoilers.

Within the first few minutes of Japan Sinks, I was quickly reminded of what life was like before the pandemic. For the characters in the anime, “before” is before Japan was rocked by a series of earthquakes. Everyone’s life is changed in an instant. The anime, based on the 1973 disaster novel of the same name, follows the Mutoh family as they try to find safety in a quake-ravaged, sinking country.

I was looking forward to a survival yarn from studio Science Saru and director Masaaki Yuasa, something that would be analogous to the times in which we live, but the series quickly descended into disaster porn. I expected that for this genre. What I didn’t expect was the general story-telling sadism aimed at the characters. That starts quickly, after the first earthquake in which the daughter Ayumu Mutoh leaves an injured friend at school. Later, however, she expresses regret for that, and her confusion and penitence fleshed out her complexities. It was hard not to be sympathetic. Then, the rest of the series put her in a series of terrible situations.

Disasters cause confusion and death, often senseless ones. As the show progresses, Japan Sinks does not shy away from killing off its cast, and each episode seems to end with someone getting killed or nearly getting killed. It felt, though, like a manipulative plot device, as in many modern TV series, with the episode ending with a punctuation mark so you’ll watch the next episode. This makes for some odd middles as well as a few episodes that veer wildly off track — most notably the episodes featuring a wacky foreigner trope and a pot-growing cult led by a clairvoyant mother and child, which seemed out of place.

This show is sad. Awful things happen to regular folks and their kids and to not-so-regular folks and their kids. Japan Sinks is not fun viewing. It goes from tragedy to tragedy, with the only moments of pause being taking group photos. Reflection happens later in the show’s more poetic and moving episodes.

Grave Of Fireflies kept running through my head while watching Japan Sinks. While the Studio Ghibli movie defines tearjerker (goodness does it ever), it doesn’t feel manipulative. The characters are thrown in a truly awful situation and do their best to survive. Death is an inevitable specter, but in Japan Sinks, it’s the main character and wants to rub your face in that fact. When things aren’t bad enough for the Mutoh family, the show makes them worse, doing everything it can to show you how horrible things are. For instance, Mari Mutoh’s husband isn’t only blown up: his hand, with his wedding ring, flies through the air and lands right in front of her.

Ayumu Mutoh’s mother Mari is a strong, well-drawn protagonist. She’s from Cebu in the Philippines, though her character is voiced by a well-known Japanese voice actor, Yokohama-born Yuko Sasaki. Along with her Japanese husband Koichiro, she has two children, Ayumu and Go. The family speaks in Japanese, which is not uncommon for families of mixed backgrounds in Japan. Go, their youngest son, speaks the occasional English, mixing the two languages. For me, what made this family so interesting is how they interact with Japanese people. They are not treated like outsiders.

At one point, an elderly man tells Go not to speak a foreign language because he is Japanese; even though he might be called haafu (ハーフ) or “half,” a term for Japanese people with mixed backgrounds, he’s not foreign. When the elderly man finds out Go and his sister are from a mixed background and that Mari is a foreigner, he is shocked. Mari quickly points out that the man drives an American pickup, to which he retorts that foreign things are different from actual foreigners. The man is in his 70s, so he probably grew up in a time in Japan when American cars were still widely sold. He smokes American Spirit cigarettes, so he does seem interested in foreign things. His uneasiness comes from actual foreigners.

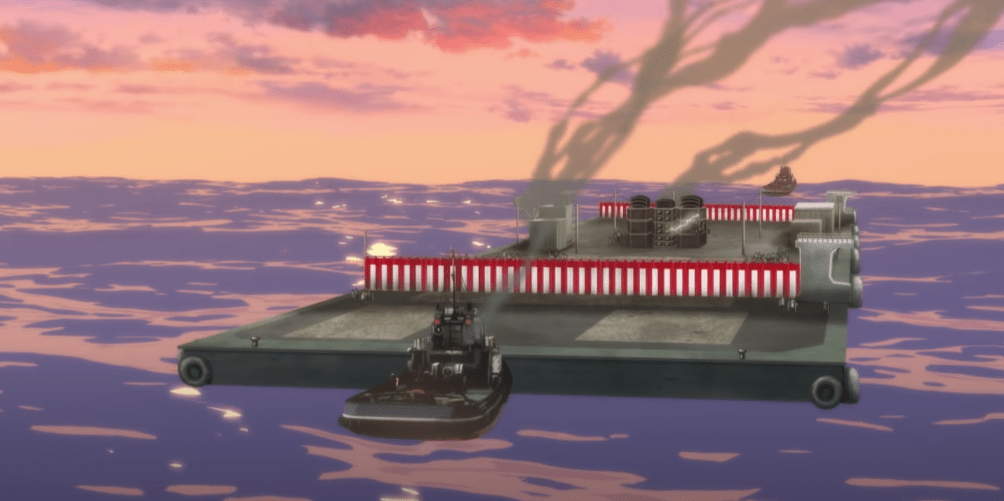

Later in the series, the Mutohs are treated like outsiders when the family tries to get on a barge, they are told only “pure Japanese” can board. Mari explains that even though her children are haafu, they are still Japanese. The man denying them entrance is confused and decides that if he counts both children as one whole Japanese person, they can board. The logic is confounding, and the show is often highly critical of Japanese nationalism and nationalism in general.

Online in Japan, there has been criticism directed at the show for this, even calling it “anti-Japanese.” Japanese people are proud and they likey to portray itself in a positive way internationally, but often Japan Sinks is an afront to that. People are bickering and selfish. There seems to be a certain ambivalence about the country among some of the characters. They don’t want to live in Japan. Towards the end, characters have a rap battle about what they hate and love about the country. It’s a silly and somewhat awkward scene, but the points the characters make are themes that run throughout the series.

(The film Shin Godzilla is also very critical of Japan, but I don’t remember it being called “anti-Japanese.” That movie had inept politicians in its sights, so that might be one reason why it could sidestep such charges.)

Some of Japan Sinks’ smartest criticism, however, is directed at the country’s bureaucracy. As the show progresses, the characters realise that they need their government-issued My Number identification to board an evacuation ship. The My Number system is still relatively new, and none of the characters seem to know their My Number cards. (In real life, the government has been pushing people in Japan to register for one, even mulling linking the number to bank accounts.) In one scene, the line to board the ship is divided into people who know their My Number and those who don’t, which needlessly complicates the whole process of getting people on the ship. Because of covid-19, the Japanese government has required people’s My Number to receive a stimulus check, so the comment on the system was timely.

I’m reluctant to say Japan Sinks is a great or even very good anime. A couple of episodes should’ve been trimmed or cut. But it’s ambitious and interesting — not the disaster stuff, which can feel like too much, but rather, in regards to the statements and commentary, the show makes about Japan and Japanese society. Mari, the main protagonist, is a foreigner but at ease in the country she calls home. Her kids have complicated feelings about Japan, as many people with mixed backgrounds do all around the world. The show strives to be more than simply a disaster anime, and even when it falls to deliver, this desire to say something makes the show stand out.

Japan Sinks isn’t what I hoped it to be, and then again, neither is 2020.

Leave a Reply