If you’d told me back in 2006 that Monolith Soft would go on to become one of Nintendo’s most talented and indispensable first-party development groups, I would have said the same thing as everyone else: “The guys who did Xenosaga?”

It’s an old joke at this point, but for years that was Monolith Soft’s reputation: a studio that put out bold, but often unpolished and incomplete games. A studio that talked big, but often failed to deliver. This reputation for overpromising and underdelivering haunted the company for well over a decade before finally managing to become the well-respected entity it is today.

This article is an attempt to chronicle the establishment of Monolith Soft, its complicated sophomore years, and the plot-twist nobody ever saw coming — and to put it all in context for those interested in one of the most interesting, most talented, and most visionary game developers from Japan.

Prologue

In the late 1980s, a young student in Shizuoka by the name of Tetsuya Takahashi found himself in a fix. Takahashi had spent all his money on a PC Engine console (TurboGrafx-16). It wasn’t even “his” money, exactly — it was his parents’, and meant to pay his tuition fees, and they’d be none too pleased if they found out how he’d spent it. Takahashi enjoyed playing games, and so it occurred to him that he should apply for a part-time job at a video game company to help fill the gap.

In particular, Takahashi had enjoyed Xanadu, a game released by Nihon Falcom for PCs in 1987. Xanadu featured a unique negative stat, dubbed “karma,” which grew if you killed friendlies. It was also considered a visually impressive game for the time. Takahashi played Xanadu on a PC-8801, and it impressed him enough that he applied for a job at Falcom, which was based out of Tokyo.

Today, Falcom is fairly well known among niche Japanese game enthusiasts for its Ys and Legend of Heroes series, but back in 1987 the Ys franchise was still in its early days. Ys II had just been released and Falcom was in the midst of other projects. Among these was an action-RPG named Sorcerian, which, like Xanadu, held a unique trait. In Sorcerian, characters were able to age, grow old, and eventually die in their golden years. Once they did, they would pass their stats on to their children. Upon joining the company, and armed with his knowledge of BASIC, Takahashi was tasked with helping creating fonts for Sorcerian. Following the completion of that task, he went to work on the sixth game in Falcom’s “Dragon Slayer” series, Dragon Slayer: The Legend of Heroes.

The Legend of Heroes was released in 1989. That same year, Falcom also released Ys III, which the company later ported to the X68000, a home computer released in Japan by the Sharp Corporation. Thanks to the abundance of memory available in the X68000, the port was able to make use of sprite art, which Falcom assigned Takahashi to work on. During his time on Ys, Takahashi decided he would much rather work on games that were designed for dedicated video game consoles (Falcom was primarily a PC developer) and applied for a part-time job at another game company in Tokyo: Squaresoft, the developer behind Final Fantasy.

Episode 1: A Fateful Encounter

By 1990 Squaresoft was in the midst of developing Final Fantasy IV, the first game in the series for Nintendo’s 16-bit Super Famicom (our Super Nintendo Entertainment System). FFIV had originally begun development on the NES, but that version of the game had been scrapped, and the project that was intended to be “Final Fantasy V” became Final Fantasy IV instead.

Takahashi joined the team as an artist and worked under series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi. Impressed by Takahashi’s attention to detail, Sakaguchi recognised him as a talented and hardworking individual who often went above and beyond the call of duty. When Squaresoft was eventually divided into three groups — responsible for the Final Fantasy, SaGa, and Mana franchises — Takahashi was assigned to the Final Fantasy team, where he could continue working under his mentor. It was here that Takahashi would himself mentor a young designer named Tetsuya Nomura, and go on to create the remarkable opening credits sequence for Final Fantasy VI — often considered one of the most memorable moments of that game.

During the development of FFVI, Takahashi would also work alongside Kaori Tanaka, a graphic designer who had joined Squaresoft in the early ‘90s. Inspired to enter game development by the original Final Fantasy and Legend of Zelda games, Tanaka first worked on Final Fantasy V at Squaresoft, then helped create the backstories for Edgar and Sabin on FFVI, among other responsibilities. Once development wrapped, Takahashi moved on from the Final Fantasy VI team to work on Front Mission and Chrono Trigger, while Tanaka joined the team developing Romancing SaGa 3, where she worked on graphics for the game’s world map and menus in addition to contributing character work. Somewhere along the way, the two designers became romantically involved with one another and married. This is where Monolith Soft’s story begins.

Episode 2: Too Complicated for Final Fantasy VII

The year 1994. Having contributed story ideas to a few of Squaresoft’s games by this point, Kaori Tanaka decided to explore her passion fo writing further. She drafted a pitch for a game about a young soldier of fortune with multiple personalities. Tanaka’s idea for the game, beyond its unique lead character, also involved summoning mythical creatures, just like Squaresoft’s Final Fantasy series. Once she finished it, Tetsuya Takahashi presented her proposal to the higher-ups at Square, pitching it as an idea for the next Final Fantasy game: Final Fantasy VII.

Unfortunately, management wasn’t very keen on the idea. At the time, they told Tanaka and Takahashi that the idea was “too dark and complicated for a fantasy,” and turned the pitch down. They went with a different concept pitch for Final Fantasy VII, and assigned Takahashi to work on the game.

Partway through the project, though, Takahashi found he fundamentally disagreed with Final Fantasy VII’s approach to world-building. The team at Squaresoft was using pre-rendered backgrounds to create the game’s environments, and Takahashi was of the opinion they should be using 3D environments instead. This, he felt, would be a much more effective approach to creating a convincing world that would immerse the player. Shortly thereafter, Takahashi approached his old mentor, Hironobu Sakaguchi, and asked if he could be permitted to work on something else instead. Takahashi had grown bored of working on a game he didn’t personally feel invested in, and was more interested in exploring his own ideas than the direction Final Fantasy VII was headed. Sakaguchi, believing his protégé was now capable of leading a project of his own, allowed Takahashi to set up a separate team — one that would work on a potential sequel to Chrono Trigger.

Unfortunately, complications at Squaresoft would lead to this plan falling by the wayside, and a sequel to Chrono Trigger wouldn’t actually go into development until a couple of years later. Luckily for the development team, Sakaguchi had their back, and with his support management allowed them to begin development of an entirely new game instead. Pitched by Takahashi and Kaori Tanaka, this new game was codenamed “Project Noah”. Takahashi had grown up reading books on philosophy, with a fondness for Freud, Nietzsche, and Carl Jung in particular. His love for complex philosophical themes — infused into nearly every game he has had a hand in — made itself known in the development plans for Project Noah, which he and Tanaka had based off her soldier of fortune idea. And what a plan it was. “Noah” was meant to be a story about artificial intelligence, love, and ultimately about the origin and future of mankind, told over a long, elaborate adventure that would require several hours to play through.

It would later transpire that Noah was, in fact, just one episode of a sci-fi epic spanning 15 billion years that Takahashi had concocted in his head. His intent, he would reveal, was to lead with the part of the story he felt was the easiest to grasp, and tell the rest through other mediums such as books or comics or animation.

If Takahashi and Tanaka were biting off more than they could chew, they either didn’t realise it or were too excited by the prospect of their new game to care. And they weren’t alone. The ambitious project had also attracted the attention of composer Yasunori Mitsuda (Chrono Trigger), character designer Kunihiko Tanaka (Ys III), and art director Yasuyuki Honne (Chrono Trigger). The team was raring to set itself apart from the rest of Squaresoft, fuelled by the grand designs outlined in Takahashi and Tanaka’s script for Project Noah. The fact that their game was going to be more ambitious in setting, more mature in tone, and more morally ambiguous than any Final Fantasy was just the start.

And then there were the mechs.

“One really clear memory I have is that no sooner had Taka-chan formed a separate team than his desk became completely covered in Gundam models and toy guns,” Sakaguchi recalled in an Iwata Asks interview. “It was then that I realised he’d always wanted to work on this kind of thing.”

Takahashi is a self-proclaimed mech nerd, one who enjoys building and customising model kits for fun. With Noah, he wanted to tell a story that not only fused his love for sci-fi and philosophy, but also one that involved mechs in some fashion. So, out went the Final Fantasy-esque summons, and in came mechs.

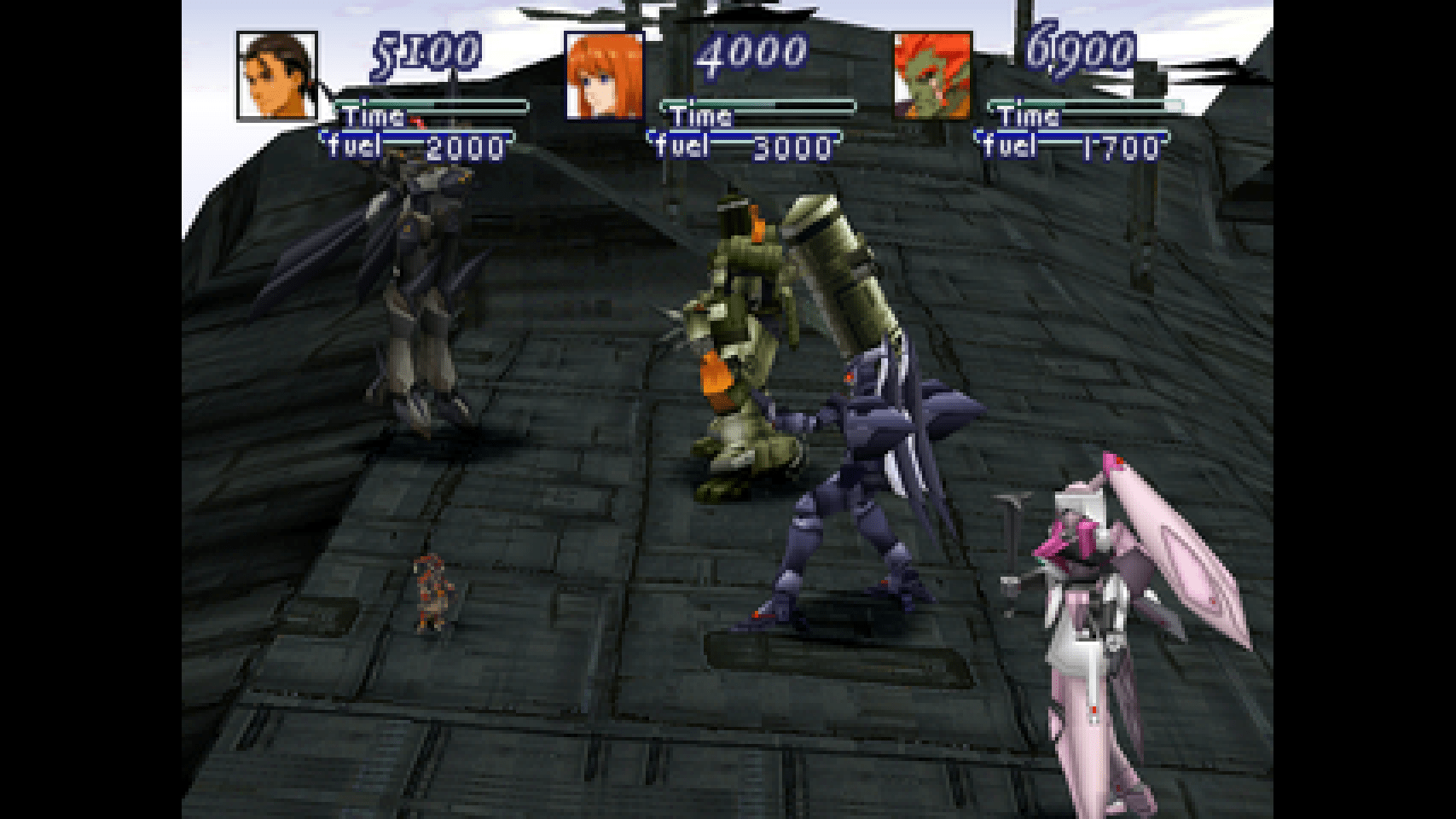

To relay this mix of elements, Project Noah was officially named “Xenogears” — the word “Xeno” being used to indicate something alien and different, and “Gears” being the term the game’s world used for mechs. Keeping with the theme of being alien and different, Takahashi’s stated goal for Xenogears was to pursue a 3D graphics style completely different from Final Fantasy VII’s, budget disparities notwithstanding.

Whereas FFVII used pre-rendered backgrounds and 3D character models, Xenogears used 3D backgrounds and 2D sprites for characters. Final Fantasy VII featured a fixed camera, while Xenogears allowed you to rotate it, letting the player see all around them to experience the places they were visiting in full. This, Takahashi said, felt more real. In real life, a place can look very different depending on whether you approach it from one end or the other. The goal was to replicate that same feeling in a game.

Squaresoft gave Takahashi and his team one and a half years to complete Xenogears. Unfortunately, with Final Fantasy VII naturally receiving the lion’s share of Square’s attention and budget, Takahashi’s was largely composed of inexperienced staff. 3D games were already uncharted territory for Japanese game developers, so an inexperienced team only served to compound the challenges.

Unsurprisingly, as the team attempted to learn the ins and outs of developing a 3D game on the job, complications arose. Making the situation even more tricky was the fact that the world and scope of Xenogears kept expanding; the game was originally meant to ship on a single CD-ROM, but was now going to require two discs to tell its story properly. Yet even with the second disc and an extra six months of development time, the team couldn’t keep up with Xenogears’ lofty ambitions. Squaresoft management suggested the only thing that made sense to them — cut the game’s short, so it could be shipped without further delay.

Stubborn to a fault, Takahashi wasn’t having any of it. Perhaps appropriately for a game that was already as bizarre as Xenogears, he proposed another solution: that the entire second disc would tell the remainder of the story in a visual novel format, without the need for more dungeons and gameplay-heavy segments. It was an unusual decision at the time, but one that made sense to Takahashi, who didn’t want to have to release an incomplete story — especially considering it was already intended to be just a single episode in the much larger saga he had planned out in his head.

When Xenogears finally came out in February 1998, it met with exactly the sort of reception you might expect: a mix of confusion and adulation, often in equal parts. It was no Final Fantasy VII — which had been released to critical acclaim the year prior — but nobody could deny that Xenogears’ plot and characters were unlike any game before it. And for players who actually managed to reach the end credits, a hint of Takahashi’s grander ambitions awaited: the game’s full title, “Xenogears Episode V”.

Somehow, the team had done it, and managed to get their troubled-but-ambitious game into the hands of customers. Even better, despite its numerous setbacks, Xenogears was received reasonably well upon release. Unfortunately, that wasn’t good enough for Squaresoft, which had allegedly viewed the project with scepticism throughout its development. A longstanding rumour suggests that Square wanted the game to sell 1 million copies before it would agree to greenlight a sequel. Unfortunately, Xenogears only managed to ship 900,000 units, and a sequel never came to fruition. Takahashi’s grand space saga would end prematurely.

Or would it?

Episode 3: The Formation of Monolith Soft

After Xenogears wrapped development,, Tetsuya Takahashi determined he and Squaresoft were no longer seeing eye to eye.

Following the massive success of Final Fantasy VII, Squaresoft decided that Final Fantasy would be its primary focus going forward. Takahashi, on the other hand, wanted to work on something new after the release of Xenogears, and it didn’t look like he was going to be able to do it at Square. In the Xenogears Perfect Works artbook, released a few months after the game, Takahashi outlined the remaining episodes in the series, and made clear his intention to flesh them out one way or the other. When it became obvious that wasn’t going to happen, he decided the best way forward was to leave Squaresoft and start a company of his own — one where he could work on the kinds of projects he wanted to. And as luck would have it, he wouldn’t have to do it alone.

Hirohide Sugiura, the producer behind Squaresoft’s Ehrgeiz: God Bless the Ring, had been a fan of Xenogears all throughout its development. Around October of 1997, when he noticed Takahashi was having trouble getting new projects off the ground at Square, the two began talking. Sugiura agreed that the ideal solution was for him and Takahashi to leave Squaresoft and establish something new. But would anybody else who’d worked on Xenogears see things their way?

Fortunately for both Takahashi and Sugiura, they did. A number of the staff that had worked alongside Takahashi on Xenogears were keen to continue working with him, including Yasuyuki Honne, the game’s art director. And so, when Sugiura, Takahashi, and Honne left Square to establish a company of their own, a portion of the Xenogears team went with them.

Over the next while, the developers shopped themselves around, speaking with various Japanese publishers in the hopes of finding one that would fund their new venture. Eventually they settled on Namco, which, according to Sugiura, was the most willing to provide the kind of financing and support that they were looking for. By October 1999, Sugiura, Honne, and Takahashi had established Monolith Software, or “Monolith Soft” for short — a subsidiary of Namco in which the publisher held a majority stake.

Soon after the new company was established, rumours began to swirl about a mysterious new game the team was developing that would bear similarities to Xenogears. Then, in early 2000, Namco put out a recruitment ad for an ambitious role-playing game it had in development at Monolith Soft. It was codenamed “Project X”.

Episode 4: The Saga Begins Anew

“Project X” was Xenosaga, a new game Monolith Soft was developing for the PlayStation 2. Of a development staff of 70, about 20 members of the Xenosaga team had worked with Takahashi on Xenogears, including art director Yasuyuki Honne, character designer Kunihiko Tanaka, composer Yasunori Mitsuda, battle designer Makoto Shimamoto, and map designer Koh Arai. Joining the core team once again was Kaori Tanaka, co-writer of Xenogears and Takahashi’s spouse. Tanaka was now going by the pen name “Soraya [Solar Year] Saga,” and would contribute to Xenosaga Episode I in the same capacity as Xenogears, writing nearly half its story and script.

Yes, that’s right — “Xenosaga Episode I”.

Like Xenogears before it, the developers conceived Xenosaga as a multi-part event, spanning numerous characters, interconnected stories, and several thousands of years. And if the plan for Xenogears struck one as ambitious, the creative vision for Xenosaga was even more so. Between Takahashi, Kaori Tanaka, and event planning director Sei Sato, the three had concocted a story that was well beyond the scope of just about any other video game at the time — and that may still be true.

At first glance, Xenosaga was a story about Shion Uzuki, the project lead in charge of designing KOS-MOS, an advanced android created to fight off an alien species known as the Gnosis. Throughout the course of the series, Shion and KOS-MOS, alongside their allies, would take part in a variety of conflicts spanning the galaxy, as the player learned of Shion’s tragic past. But as you dug deeper and uncovered more of its story, Xenosaga would turn out to be about much more than your handful of party members.

At a broader level, it was a game about the creation of the universe itself. About human consciousness and the preservation of the soul after the body’s death. About the cycle of death and reincarnation. And as if that weren’t complex enough, the series chose to tie these narrative threads together using overt religious themes, as Japanese media is wont to do. The entire epic, according to Takahashi, was planned to be told over the course of six episodes, with Episode I alone taking up two entire DVD-ROMs — a rare requirement for a PlayStation 2 game.

Biting off more than it could chew was Monolith Soft’s trademark by this point, and while this was partly what endeared the developer to fans, it was also a recipe for good old-fashioned disaster. By Takahashi’s own admission, production on Xenosaga Episode I began while the team was still being formed. To make matters worse, many of the employees were inexperienced, leading to complications just as with Xenogears before it. (Takahashi would later reveal that the graphics engine meant to be used for Xenosaga Episode 1 was completed a mere six months before the deadline for its release.) With development only properly kicking off in late 2000, Namco eventually felt forced to delay Xenosaga beyond its early 2002 release window.

As with Xenogears, the team needed to learn the ins and outs of creating such a massive, ambitious game on the job, including when to cut back on some of their more ambitious ideas. Player movement and interaction with enemies was far more advanced than in Xenogears, but an ambitious idea to allow the player to roam the gameworld in their mechs had to be scrapped, owing to their size and the resulting complications. The game’s several hours of voiced events and FMV cutscenes would also require an immense amount of work. The team had its work cut out for it.

Eventually, as with its predecessor, Takahashi and co. had to scale back Xenosaga Episode I’s story ambitions to get the game out. A great deal of content ended up being cut, with Takahashi claiming in an interview that Episode I ended up with only 20% of the content initially planned for the first chapter in the Xenosaga story. And while reactions to the game were largely positive, sales weren’t, with Monolith Soft acknowledging that the sales figures for Episode I proved disappointing.

This necessitated a swift change in plans. An immense amount of time and money had gone into producing Xenosaga Episode I. There was no feasible way Monolith Soft would be able to produce five more games of the same scale to wrap up Takahashi’s six-arc storyline within a reasonable timeframe. And so, the developers heavily reworked the script Kaori Tanaka and Takahashi had initially written for Xenosaga Episode II to accommodate a shorter story. Despite being one of the original creators of the series, Kaori Tanaka was not brought back to work on Episode II. Studio co-founders Tetsuya Takahashi and Hirohide Sugiura took a step back from working directly on the second episode as well.

In Takahashi’s place was a new director, Koh Arai. In the place of Sugiura was a new producer — one who worked directly for Namco, Monolith Soft’s parent company. Alongside the drastic changes made to its story and creative staff, Xenosaga Episode II also used an entirely overhauled graphics engine and took a much more realistic approach to character design, in hopes of broadening the game’s appeal.

Meanwhile, the rest of the Monolith Soft team was split up to work on a wider range of projects. Monolith’s third co-founder, Xenosaga art director Yasuyuki Honne, was assigned to develop an entirely different role-playing game for Nintendo’s GameCube console.

According to producer Shinji Noguchi, the idea for this game was to create a “true RPG” for the GameCube — one that could be grown into a tentpole franchise for that platform, which didn’t have many role-playing games compared to the PlayStation 2. Titled “Baten Kaitos,” the game was originally conceived in 2001, with a story written by Masato Kato of former Squaresoft fame. Unlike Xenosaga, Baten Kaitos used a card-based battle system and was designed to be far more manageable in scope than Monolith Soft’s prior titles. It was developed in collaboration with Tri-Crescendo, another Japanese developer that had previously contributed sound work to the Star Ocean series and would later collaborate with Namco on a multitude of projects.

Upon its release in 2003 Baten Kaitos was well-received, prompting Namco to greenlight a second game that would serve as a prequel. This was in contrast to Xenosaga Episode II, which came out in Japan just a few months later and faced harsh criticism from audiences and critics, with the consensus being that the game’s story was needlessly complicated and did relatively little to further the plot established in Xenosaga Episode I. Following its release, Namco and Monolith Soft publicly acknowledged that the Xenosaga series had been shortened from the initially planned six episodes to just three, and that the story would end with the forthcoming third game.

Interlude

The year is 2006. Monolith Soft is at the lowest point in the history of its existence. Xenosaga Episode III has wrapped development and been released, finally bringing the series to a close. While the response to Episode III has been significantly more positive than Episode II, the franchise as a whole is considered something of a flop, having failed to deliver on most of its promises.

Elsewhere, another Japanese video game company is having better luck. At E3 2006, Nintendo makes a splash with the reveal of a revolutionary new game console: the Wii.

With a simple controller that resembles a television remote, the goal of this new console, Nintendo says, is to make games more accessible to a wider audience. The company reveals a number of new titles designed to achieve this — most notably Wii Sports, a simple motion-controlled game in which players engage in tennis or boxing or bowling matches against one another. But there are also more traditional games for the Wii, including a new Zelda, a new Metroid Prime, a new Mario, and more.

Among these “core” titles is also a new game developed by none other than Monolith Soft, called Disaster: Day of Crisis.

Episode 5: Two Monoliths Meet

On April 27th, 2007, Namco Bandai and Nintendo made an announcement that hardly anyone could believe: Nintendo had acquired Namco subsidiary Monolith Soft, the developer behind the Xenosaga series.

Namco, which previously owned a majority stake in Monolith Soft, stated in a press release that it had sold 80% of its shares in the studio to Nintendo, giving the Kyoto giant nearly full control of the development team, and effectively making Monolith Soft a first-party Nintendo developer. By the early 2000s, Internet forum culture was firmly established, and reactions to the news were as harsh as you might expect.

“Nintendo got screwed!” proclaimed one poster on a video game forum.

“I heard Namco had to pay Nintendo to take them,” joked another.

“I look forward to Super Mario Existential Philosophy Musings,” said a third.

The jokes wrote themselves. Nobody quite understood what was going on. What could Nintendo, known for its focus on tightly designed, expertly polished games, possibly want with Monolith Soft?

Namco’s press release offered little clarity, outside of a vague statement mentioning that a deal had been struck between it and Nintendo to foster the growth of the infamous RPG developer. Even odder was the fact that Namco had chosen to retain a part of its shares in Monolith, and would continue to collaborate with it on certain games to be published under the Namco label, thereby making Monolith a shared asset of sorts. It was all very odd.

As the years passed, additional information provided a little more insight into what had happened. While Takahashi and co were first establishing Monolith Soft under Namco, they were dealing directly with Namco founder Masaya Nakamura. According to Monolith Soft co-founder Hirohide Sugiura, Namco treated the studio with respect under Nakamura’s watch, which was part of the reason Monolith agreed to operate as a subsidiary of the publisher in the first place. Unfortunately, between the complicated development cycle of the Xenosaga games and the merger of Namco with Japanese toy maker Bandai, Monolith’s owners viewed the developer’s desire to create ambitious new worlds and stories with increasing scepticism. Nakamura had stepped down from the role of CEO a few years prior, which meant none of Namco Bandai’s higher-ups had Monolith Soft’s back.

Namco Bandai’s scepticism was understandable. By the time Xenosaga Episode III came out, the industry was already exploring HD game development on the Xbox 360. Developing high-definition games was an expensive affair, and Japanese game developers in particular were having a difficult time acclimating themselves to the higher specs. Allegedly, some of Namco’s own internally developed games — like Tales of Vesperia — required funding from Microsoft during development. All said and done, it made sense that Namco Bandai wasn’t willing to pour even more money into Monolith Soft, a studio that had historically seen more misses than hits.

Luckily for Monolith, other parties were interested in the studio’s potential — namely Nintendo president Satoru Iwata, who had an interest in both Namco and Bandai. Iwata became president of Nintendo in 2002, while Monolith Soft’s main development team was still busy working on Xenosaga. In 2003, Iwata’s Nintendo purchased a 2.6% share in Bandai prior to the company’s merger with Namco. (At the time, a member of Bandai’s founding family claimed that the company’s board was conspiring to facilitate a complete takeover of Bandai by Nintendo, but the rumour was denied by both sides.)

Iwata also began collaborating with one of the Monolith Soft’s three co-founders — Yasuyuki Honne, art director of Xenogears — to conceptualise a new Earthbound game for the GameCube. While that particular project never saw the light of day, Nintendo instead made arrangements with Namco for Monolith Soft to develop other games for its platforms. These manifested in the form of Baten Kaitos and its sequel Baten Kaitos: Origins, following which work began on a third game, this time for the Wii, in the form of Disaster: Day of Crisis. As a project, Disaster wasn’t nearly as grand in scope as Xenosaga, but still presented significant challenges of its own. At some point during the development of this game Monolith Soft was given the choice to change hands.

“That’s when we received consultation from Nintendo’s then-managing director Shinji Hatano,” Sugiura would reveal in an interview on the Monolith Soft website years later. “Hatano-san told us, ‘Just go out there and make something that can’t be found elsewhere in the industry, something original with an independent spirit.’ That was just the thing Monolith Soft looked to accomplish. And that’s when it was decided that we would become a subsidiary of Nintendo.”

Comments made by Satoru Iwata after the Monolith Soft acquisition suggested that the company’s interest in the studio was at least partly due to its relationship with Sugiura. Once Namco and Bandai merged and Monolith Soft saw the writing on the wall, Sugiura managed to convince Nintendo that Monolith could contribute something unique to its portfolio. Following the acquisition, Iwata said to Nintendo’s investors: “In the case of Monolith Software, Mr. Sugiura, the president, and Nintendo have a long-term relationship. How Mr. Sugiura thinks is close to how Nintendo thinks. The software Mr. Sugiura would like to create is in line with what Nintendo would like to have for its platform. So, we thought that Nintendo should support this idea, and we decided to take action.”

In the grander scheme of things, the acquisition of Monolith Soft wasn’t interesting just because it seemed like an odd (and rare) move for Nintendo to make, but also because it suggested that Nintendo was interested in covering a broader range of genres on its platforms. In particular, while the NES and SNES were known for birthing several notable brands in the role-playing genre, Nintendo home consoles had lacked big-budget RPGs since the N64, conceding the genre almost entirely to Sony’s PlayStation and PlayStation 2. And so, if it couldn’t have Final Fantasy back, maybe it just made sense for Nintendo to create its own marquee role-playing games instead. Perhaps this was Nintendo acknowledging a gap in its portfolio, and taking steps to close it.

As for the staff at Monolith Soft, naturally there were concerns over what working for Nintendo would be like. Most notably, the studio would be restricted to developing for Nintendo systems, while other developers — including Monolith’s Japanese peers — were starting to take more of a multiplatform approach to developing games. One thing was for certain, though: Whatever the future held, it was going to be an interesting time for Monolith and fans of the studio’s output.

Episode 6: A Shift in Development Style

Prior to its acquisition by Nintendo, Monolith Soft was developing an action game titled Disaster: Day of Crisis for the Wii. Inspired by Hollywood action and disaster movies, the game was unlike any Monolith Soft title prior, with a mix of shooting, driving, and platforming game segments set amidst an earthquake and an impending nuclear threat.

Disaster, it was revealed, was being directed by Keiichi Ono, an event designer from the Xenosaga team, with another Xenosaga veteran, Koh Kojima, serving as the game’s lead designer. But wait a minute…where was Tetsuya Takahashi?

As it would turn out, Takahashi was already juggling work on his next two projects — one of which, a smaller game for the Nintendo DS, was unlike anything Monolith had ever created before.

Soma Bringer was a hack-and-slash, co-op action-RPG, along the lines of Diablo. As in Blizzard’s game, the player could choose from several different characters, each one representing a different class and style of combat, and up to three players could team up and play together over local wireless. And while the multiplayer mode was to be a significant part of the game’s appeal, Soma Bringer was designed so one could enjoy it in single-player as well, with a wide range of loot and skills available to dabble in. The idea was to create a game that fit the characteristics of a portable device, and Takahashi felt that the pick-up-and-play aspect of an action-RPG was a good fit.

“At first, we experimented with the format of a standard RPG,” he revealed in a 2008 developer interview. “However, when thinking about things that were feasible ‘because it is on the DS’ — such as playing with everyone or enjoying the game even if only playing in short bursts at a time — we thought that an action-RPG was more appropriate for what we wanted to make, so we discarded what we’d worked on so far and remade it from scratch. I believe that, as a result, we managed to express the feeling of exhilaration and speed, which only exists in action games, quite well.”

For Soma Bringer, Takahashi and his team approached development very differently from how they had in the past. Thus far, Monolith Soft had created games by drafting an extensive story up first, and moulding the game around that story, often expanding its scope and losing control of its budget and schedule in the process. This time, however, they began by assessing the resources available to them first and foremost. Using this information, they calculated how many chapters and dungeons worth of content they could create, and structured the game’s story around these estimates.

It was an awfully scientific and responsible approach to game development — quite unlike Monolith Soft. Perhaps the fact that the game was being developed in collaboration with Nintendo — which hadn’t yet acquired the studio — was making Takahashi and his team plan projects out more carefully. Or perhaps a device like the Nintendo DS demanded a more planned approach. Regardless, Soma Bringer’s story was still intended to be every bit as engrossing and ambitious as one would expect of a more “traditional” Monolith Soft title. Kaori Tanaka, Takahashi’s wife, longtime collaborator, and co-writer of Xenogears and Xenosaga Episode 1, was the game’s scenario writer. As always, Tanaka and Takahashi had drafted plans for a larger universe while penning the game’s story, and cherry-picked the elements they felt were most appropriate for an action-RPG to include in the final product. That way, if the opportunity ever arose, they would be able to expand upon the game’s universe in the future. Even if Monolith Soft was taking a more responsible approach to Soma Bringer’s development, Tanaka and Takahashi’s love for creating new worlds was as present as ever, and it showed in the rich story that made its way into the final product.

By this point, the couple also had a son and daughter in elementary school, which Takahashi has noted is one reason that Soma Bringer was designed with a focus on simplicity, cooperative action, and loot — all packed in with a classic Monolith Soft-style story, complete with all the requisite twists and turns. Soma Bringer hit Japanese stores in 2008, meeting with largely positive reviews and praise for its simple controls, excellent music (Takahashi’s friend and collaborator Yasunori Mitsuda composed its soundtrack), and interesting story. Simply put, it was a win — something Monolith Soft desperately needed at the time.

Unfortunately, Soma Bringer was never localised and released outside Japan in an official capacity, greatly diminishing any impact it had on the company’s reputation internationally. (A fan group released a competent and mostly complete translation patch in 2009.) In the West it remains an underappreciated piece of Monolith Soft history, which is unfortunate because it marked the start of a new approach to game design for the studio — one that would shape its next game and the studio’s brand for years to come.

Episode 7: Crafting a JRPG Masterpiece

During the development of Soma Bringer and Disaster: Day of Crisis, Hitoshi Yamagami, Monolith Soft’s handler at Nintendo, decided that the company’s third Nintendo-funded project should be an RPG, since that was the genre the studio had historically specialised in. It would transpire that this was a wise decision — while Disaster was an interesting experiment, it went through a difficult development cycle and was at one point “indefinitely delayed” as the development team struggled to hammer it into an acceptable state. When finally released in 2008, it was considered an utterly mediocre effort, lacking both polish and vision.

Early in the development of Disaster, Nintendo and Monolith’s courtship was in full swing, allowing for closer collaboration between the two entities on the studio’s next project. Shinji Hatano, who was in charge of Nintendo’s licensing department, gave the studio a single piece of advice: Develop games with a “romanticist” approach. What Hatano meant was that Nintendo wanted Monolith Soft to develop games in which the story and world would resonate with and inspire people — the kind of games that Monolith Soft loved to make. And so, with Xenosaga Episode III having wrapped and Soma Bringer properly underway, Takahashi began brainstorming a second RPG under Nintendo, around Hatano’s suggestion of romanticism as a theme.

His concept? To explore the idea of human beings living on the bodies of gods.

A few months after Takahashi and his concept team settled on the vision for their new project, they presented Nintendo with a physical model of two enormous god-like beings engaged in combat. They described, in immense detail, how they wanted players to start out at the bottom of one of the god-like figures and explore along the bodies of the two giants, working their way up from the legs to the head. Each area would exhibit different weather patterns and terrains based on what part of the giants’ bodies it was situated on. Areas exposed to the light would be sunny, while those in shadow would be frigid. It was a solid pitch — and one that Yamagami liked very much. There was just one problem: that model of the two gods was all Takahashi had. There was nothing else.

“I assumed that, as they had gone to the trouble of making this model, they must surely have also settled on the finer details. But it turns out that this model was all there was,” Yamagami, the game’s producer at Nintendo, would recall in an Iwata Asks interview. “I wasn’t aware that [Takahashi] had this approach to making games, so I was initially rather taken aback when I found out that nothing was really fixed aside from the model.”

By 2007, all the pieces were firmly in place for the familiar Monolith Soft cycle to begin anew. The studio had found itself a new publisher with deep pockets. Said publisher had agreed to fund the studio’s outlandish and ambitious concepts. Finally, a pitch for the studio’s first major new game had been prepared, with the usual involvement of gods and monolithic beings and possibly questions about mankind’s place in the world — all larger-than-life ideas that are typically difficult to convey through the medium of video games. Naturally, there was also no real understanding of just how all of these elements were meant to come together, or what the challenges involved with developing this new game were going to be.

There was, however, one major difference this time around: Nintendo was not Namco Bandai. Nintendo was certainly not Squaresoft. It was Nintendo, a company run almost entirely by game designers and known for being incredibly hands-on with the games it published — even those developed by external studios. And so, once Monolith Soft had officially become part of Nintendo, Yamagami got to work on giving the team the support and guidance he felt it needed for its new project to succeed.

Recognising that the studio’s primary strength was its vision and not an aptitude for logistical planning, Yamagami assigned a team at Nintendo to collaborate with Monolith. Nintendo tasked two members of this team with looking over a script Takahashi had drafted to provide feedback. In parallel, it ask the studio to develop a prototype for its proposed game, consisting of one complete area that would be created and polished to the quality of a final, shippable product. This, Yamagami felt, would give everyone involved a decent idea of how long the full game would take to develop, and what challenges developing a semi-open-world game set on the bodies of gods would involve. It was how Nintendo was used to designing its own games — through extensive prototyping and iteration — and it was how Monolith Soft would be required to design this one if it wanted it to go into full production. The new development style that the studio experimented with for Soma Bringer was now in full effect.

Despite some initial resistance to these demands, the staff at Monolith Soft eventually had no choice but to abide by Yamagami’s instructions, and got to work on their prototype. To their surprise, they found this a much more motivating approach to development.

“When we actually did it, it was brought home to the staff very clearly and concretely that this was the kind of target we could work towards,” director Koh Kojima recalled in Iwata Asks. “It also made us aware of how much time we’d need to spend to produce one section, which was really great.”

Meanwhile, Takahashi’s script for the game — tentatively titled “Monado: Beginning of the World” — had been scrutinised by Yamagami’s team, which was starting to ask some tough questions about whether or not players would understand some of the elements outlined in the story. While Takahashi was the writer and visionary behind this new game, Yamagami’s team at Nintendo was acting as his editor, pointing out flaws and gaps wherever it felt aspects needed to be made clearer to the player. It was the sort of symbiotic relationship that Monolith Soft had lacked in its past experiences with publishers, and it was doing the studio a whole lot of good. Even great writers, as they say, need an editor.

Most importantly, Nintendo wasn’t just providing feedback and edits, but also financial and moral support. As always, Takahashi wanted to collaborate with his longtime friend, Yasunori Mitsuda, to compose the music for Monado, and not only did Nintendo approve of the collaboration with Mitsuda, it also approved a plan for an all-star team of excellent composers to work on the game’s music — each with their own distinctive style and approach. (To put this in perspective, the game’s soundtrack received an entire Iwata Asks interview of its own, featuring a lineup of extremely talented composers.) And when the time inevitably came for Monolith Soft to realise that it had, once again, bitten off more than it could chew in terms of scope, Yamagami appealed for an extension to the development schedule, encouraging the team to see its vision through all the way to the end.

In Nintendo, Monolith Soft had finally found itself a collaborator that truly understood its strengths and weaknesses, and knew how to help. And hopefully, this time, things would work out between studio and publisher. After all, everybody was keen to avoid another Xenosaga incident — most of all the team at Monolith Soft, which felt it needed to redeem itself in the eyes of the industry and its fans.

Following a brief tease at E3 2009, Monado surfaced under its final title six months later: “Xenoblade”.

The name sought to honour Monolith Soft’s previous body of work, and to indicate that, like the studio’s previous games, this too would be something alien and different. The goal was to give the world a JRPG masterpiece, and to prove that Monolith still had the chops to create great games.

“We released three games in the Xenosaga series, but they weren’t very well received,” Takahashi would say in another Iwata Asks interview. “It was really mortifying. All of the young team members felt that way, not just the leaders. So we all decided, ‘Next time we need to make a game that players will enjoy.’ So that made the atmosphere during the Xenoblade Chronicles development very different compared to other games.”

Episode 8: The Evolution of the JRPG

The collaboration between Monolith and Nintendo had worked. By 2011, it had been widely established that Xenoblade — titled Xenoblade Chronicles for its Western release — was the best role-playing game Japan had produced in years. It was the masterpiece Monolith had hoped to create.

Xenoblade Chronicles won praise for its unique premise, incredibly well-crafted world map, excellent English dub, and most of all the sense of openness and freedom it offered the player — something Square Enix’s Final Fantasy XIII, which was meant to be the defining JRPG of the generation, had utterly botched. Where Final Fantasy XIII had failed, Xenoblade helped spark the JRPG comeback that would carry over into the next console generation, pulling Japanese games off of the sidelines and back into the limelight. To gamers, it was a reason to care about Japan again. To JRPG fans, it was a sign of hope — vindication of their favourite genre, following years of apathy from the industry at large. To video game critics, it was a change in the ongoing narrative about how Japan was becoming irrelevant. And finally, to fans that had once mocked the idea of Nintendo acquiring Monolith Soft, it was an eye-opener.

All eyes were now on Takahashi’s studio. What could Monolith Soft possibly pull out of its hat to outdo a game as well-crafted and ambitious as Xenoblade?

Two years later, on January 23rd, 2013, the studio answered that question with the announcement of a Wii U game codenamed “X”.

Unlike its predecessor, which had gradually gained popularity through word of mouth, “X” was a hit with fans from the moment of its reveal. The game’s expertly edited debut trailer promised a vast, outlandish alien world even larger than Xenoblade’s, with the player facing off against enormous extra-terrestrial lifeforms using a mix of ranged and melee weapons to a dramatic score. At one point in the trailer, the player character casually ran up to a giant mech perched atop a cliff, climbed in, and took off, soaring over a vast landscape, all without the faintest hint of a transition or loading screen. Another shot revealed that the mech could transform into a vehicle on-the-fly. Yet another suggested online multiplayer, and that you could even use the mechs in the game’s multiplayer mode. And to top it off, the trailer ended with a giant, red “X” at the end.

Just what was this game? How did the mechs work? How could it possibly look so good running on a Wii U? And what was that red “X” all about? Was this some sort of remake or sequel to Xenogears?

As it would turn out, no, it wasn’t a Xenogears remake — but it was, in some ways, the spiritual successor to that game. X, like Xenogears, was attempting to do something games had never done before in terms of scope. In the case of X, Monolith Soft sought to create a vast, freely explorable open world — perhaps the largest of any game ever — in which you could go literally anywhere, any time. And you could do it in a transforming mech. One that could walk, or drive, or fly, which was fully under your control, deeply customisable, and capable of both combat and peaceful exploration. X was, as Monolith Soft would later reveal, the studio’s ideal mech game. Something it had been wanting to create for years.

It was also what Monolith Soft said it considered to be the next step in the evolution of JRPGs.

“X,” whose full title was revealed to be Xenoblade Chronicles X, was Monolith Soft trying to prove a point — that JRPGs didn’t have to conform to a linear structure, or that they couldn’t be social experiences, or even that they couldn’t compete with major games developed in the West.

The more Monolith Soft revealed about the game, the more there seemed to be no end to the depth it offered. You could create and customise your player character from scratch. You could switch between a number of different character builds and jobs. You could purchase and craft a wide array of different equipment and weapons, freely swapping between ranged and melee tactics in combat. You could recruit NPCs you met out in the game’s world into your party. You could play certain missions with a friend online, following which you could find their avatar in your game, and even recruit them into your party. You could purchase a variety of different mechs, each with their own strengths and weaknesses, and freely swap between them, outfitting each one with your desired equipment and assigning it to members of your party. You could even open up an almost Photoshop-like interface and customise, right down to the tiniest detail, every aspect of the look and colour of your mech.

Most importantly, as promised, you could go just about anywhere in the game’s world, at any time, and had the freedom to get yourself in whatever trouble you felt like. The game wouldn’t stop you.

Xenoblade Chronicles X used an ingenious three-layered approach to exploration. First, you would explore its enormous world on foot. Then, once you had a mech, you would explore it on wheels, making the scale of the world a little bit more manageable. Finally, once you acquired the ability to fly, traversal became much quicker, and you could focus on uncovering even more of the planet, discovering areas you couldn’t previously reach. Xenoblade Chronicles X was, for all intents and purposes, the closest thing to Breath of the Wild before Breath of the Wild. And, in one of those extremely rare instances, when it came out, the game was just about everything it promised to be. It was a game with a vision — a sometimes-controversial vision in the eyes of more conservative JRPG fans, but one that stuck to its guns and executed well on everything it promised to do.

Xenoblade Chronicles X was a game that proudly shunned design choices often made by more traditional Japanese RPGs, basked in its almost singular obsession with player freedom and customisation, and even managed to include an incredibly intelligent multiplayer element, designed to appeal to players who were wary of going online. Its multiplayer involved an ingenious mix of asynchronous and co-op missions that made the whole game feel like you were playing in the company of others even if you weren’t necessarily sharing the same screen. X subscribed to the “gameplay-first” school of design through and through, and like the best games do, managed to contextualise every one of its features within its story: You were among the last living men and women of Earth, stranded on an alien planet. It was your job to explore and chart this world, protect your people against the looming alien threat, and help human civilisation re-establish itself. Go.

Diehard Monolith Soft fans even got to savour a bit of the classic, bittersweet frustration that accompanied the studio’s previous games. Case in point: Once you completed its main story, Xenoblade Chronicles X ended on a cliffhanger, with no further explanation as to what was going to happen next. A development insights artbook would later reveal a wealth of planned content that never made it into the final product, cut in order to finish the game on time. Vintage Monolith Soft.

In an internally conducted interview, Michihiko Inaba, a member of the Monolith Soft development team, stated: “I want to show that Japan can still keep up with the USA when it comes to next-gen technology. Our goal is to become something like the developers of the Fallout series, Bethesda Softworks.”

That quote says it all. Xenoblade Chronicles X was not only an extremely ambitious game for a Japanese developer, it was also the first real glimpse of what Monolith Soft could achieve with all that pent-up ambition it had been unable to properly channel for years. And when Zelda: Breath of the Wild famously suffered its first delay, Nintendo promoted Xenoblade Chronicles X as its marquee title that holiday season — one that fans fervently discuss even today, and hope to see ported to the Nintendo Switch.

Epilogue

The year is 2020. It’s been a decade of home runs for Monolith Soft, topped off by an immensely successful remaster of the original Xenoblade Chronicles. Since its acquisition by Nintendo in 2006, the studio has developed three role-playing games that have been incredibly well-received (four if you count the Japan-exclusive Soma Bringer). Two of these — 2017’s Xenoblade Chronicles 2 and 2019’s remaster of Xenoblade Chronicles — are on track to sell about 2 million units apiece, becoming the highest-selling titles Monolith Soft has ever released.

In light of the studio’s successes, Nintendo has allowed Monolith the luxury of expanding. The company now has three different studios — one in Tokyo, one in Kyoto, and one in Iidabashi. In addition to Monolith developing its own genre-defining games, its studios also had a hand in assisting with the development of numerous Nintendo titles, most notably The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, for which a significant portion of the Xenoblade Chronicles X team helped design environments, artwork, and other key aspects. (Meanwhile, Monolith Soft Kyoto has produced art assets for a number of Nintendo hits, including Animal Crossing: New Leaf and Splatoon 2.)

Over the years Monolith Soft has arguably grown into one of Nintendo’s most important and invaluable first-party studios. And if a recruitment drive on the studio’s website is to be believed, it’s just getting started.

A few years ago, Monolith Soft put out a recruitment notice for a new game — a project that it said was both ambitious and different from what the Monolith Soft brand was known for. Accompanying the recruitment notice was a series of pictures that suggested a medieval fantasy setting, complete with knights and dragons. For this project, Monolith Soft said, it was seeking programmers and designers that had prior experience working on action games. In addition, the company was also looking for staff familiar with medieval fantasy and Western entertainment trends.

That was May 2017. In 2019, the studio began recruiting again — and this time, it sounded like it might have been hiring for a new Legend of Zelda game all along.

On March 28th, 2019, a recruitment notice went up on the Monolith Soft website. It was on a page titled “Production 2,” implying a second production team at the studio. It featured an image of the Triforce and the Gate of Time from The Legend of Zelda, and mentioned that Monolith Soft was hiring programmers, designers, technical artists, support staff, and other roles to work on a game in the Zelda series — presumably what we now know as the sequel to Breath of the Wild.

Meanwhile, a different recruitment notice — under the title “Production 1,” the Xenoblade team — was hiring for a separate project. Accompanying it was a message from Tetsuya Takahashi, chief creative officer of Monolith Soft and father of the “Xeno” series of games.

“Why are we hiring?” Takahashi asked on the recruitment page. “It’s simple — we’re understaffed.”

Takahashi’s message went on to reveal that, thus far, Monolith Soft had been punching above its weight, developing games that were incredibly ambitious in scope with a relatively small team. This had worked so far, but posed a number of challenges. Now, however, the time had come for the studio to expand, in order to provide fans with even better experiences. And so, Takahashi stated, Monolith Soft was hiring for every position from level designers to programmers to character designers to quest planners — all for a brand-new RPG that would continue in the vein of Xenoblade Chronicles, Xenoblade Chronicles X, and Xenoblade Chronicles 2.

In 2020, Monolith Soft is among the best and most beloved of Japanese game developers. It has not only helped make Japanese RPGs relevant again, but has also made itself an invaluable asset to its parent company, helping shape some of Nintendo’s best games this past decade. Few other developers have displayed such fortitude, such enormous growth, and such a willingness to evolve — and even fewer that have maintained such a strong, focused vision through all their ups and downs over the years. A true Monolith, then.

Ishaan Sahdev specialises in game design/sales analysis. He’s the author of the book “The Legend of Zelda – A Complete Development History.”

Leave a Reply