You may have heard rumblings of a magical box capable of flawlessly running games from old-school arcade titles up through the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis. That box is called the MiSTer, and over the past couple of years, it’s completely transformed the retro emulation scene. I’ve been playing with one several months now and can confirm that yes, it rules.

What’s the difference between software- and hardware-based emulation?

“Traditional” emulation is software-based. Developers of popular emulation software create a program that tricks game ROMs — that is, copies made from cartridge- and disc-based games, that you can store on your computer — into thinking they are running on original hardware. These are the emulators you download to your computer or which come preinstalled in retro TV consoles like the NES Classic. Software emulation can be great. It can also be flawed. Some games run poorly, graphics get distorted, sound gets garbled. The games can exhibit slowdown and input lag not present on original hardware. Software emulation can be kind of a crapshoot.

Enter the field-programmable gate array, or FPGA for short. An FPGA is an integrated circuit that contains an array of programmable logic blocks that the end-user (that’s you) can configure as they see fit. These logic blocks can be rearranged on the fly to simulate video game consoles (and other circuit-based devices) at a hardware level. Reimplementing them, basically.

Instead of tricking a game ROM with software, you can program an FPGA to more or less be the original console hardware. Configure an FPGA just right, and for all intents and purposes, the game ROM will be running on a highly accurate reproduction of the original hardware. This can make some of the problems inherent in software emulation, like hard-to-avoid input lag, just go away.

We’ve seen FPGA emulation in action before. Analogue’s line of pricy prestige NES, SNES, Genesis, and soon Game Boy consoles each utilise FPGAs configured to simulate the hardware of individual systems. They work wonderfully, are incredibly well-engineered, and come highly recommended if you’re looking to emulate one or two specific gaming platforms (and don’t mind navigating Analogue’s notorious availability issues).

What is the MiSTer, aside from a bestselling novel by E.L. James?

The MiSTer project, often referred to as MiSTer FPGA, is an open-source project that harnesses the configurability of the FPGA to emulate everything from old school arcade hardware to early computer platforms to the first several generations of handhelds and consoles. The FP in FPGA stands for field-programmable, so why lock into a single console when you can reconfigure logic blocks into any gaming hardware your heart desires? The name MiSTer, as far as I can tell, comes from the MiST project, originally meant to emulate the Atari ST and Amiga 500.

From those humble beginnings, the MiSTer project has evolved into a massive community endeavour capable of simulating nearly 30 consoles and computers, with cores for more retro platforms being worked on every day. We’re talking old computers like the Commodore 64, arcade classics like my beloved Mr. Do! and Robotron 2084, to mainstream consoles like Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo. As of this writing, project contributors are trying to get a PlayStation core up and running. Sega Saturn is making headway too. MiSTer is an ever-evolving box of retrogaming wonders.

What’s a MiSTer made of?

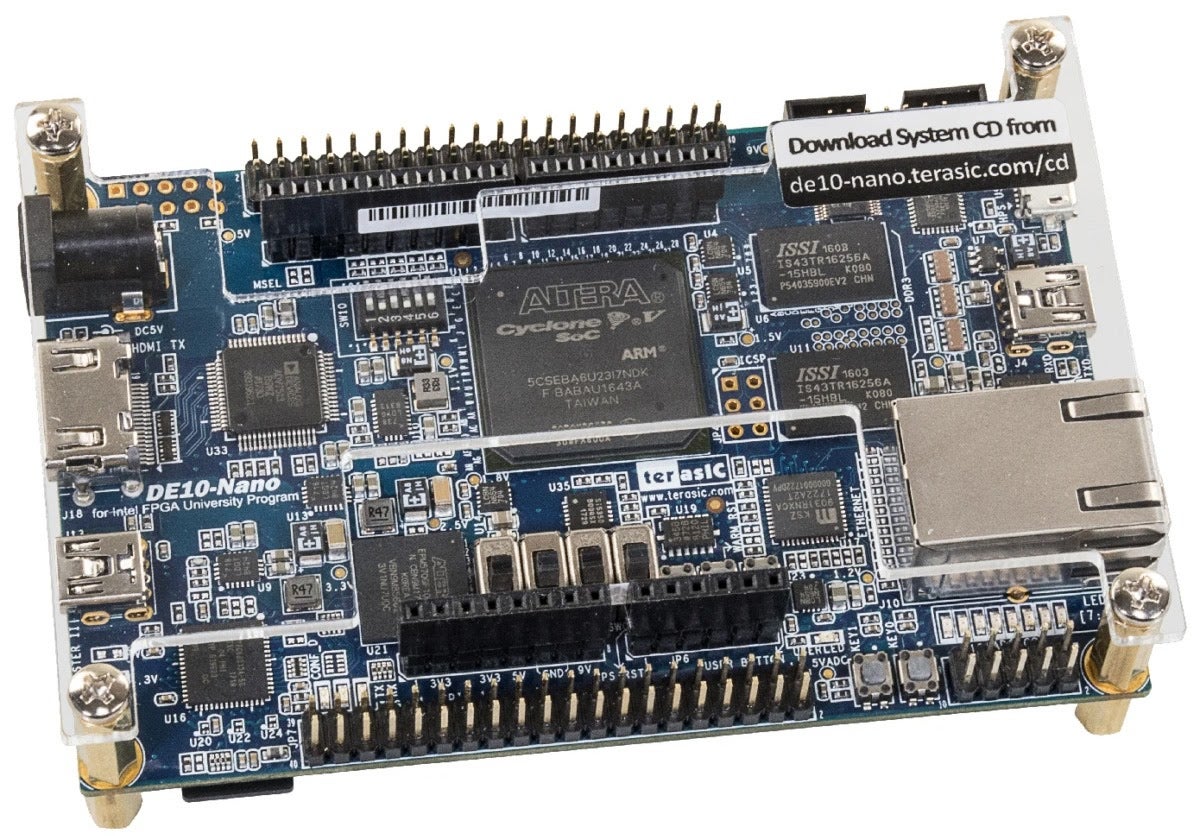

The MiSTer, being an open-source project, comes in many shapes and sizes, but there is a basic configuration that’s really popular with newcomers to the scene. It all starts with a DE10-Nano board. The most expensive aspect of building a MiSTer, the DE10-Nano runs around $US180 ($243). It houses the FPGA that makes the whole thing work, along with an ARM processor and several I/O ports, including an HDMI-out that upscales up to 1080p.

If you purchase the DE10-Nano from MiSTer Addons, the go-to site for MiSTer supplies, it comes with an 8GB micro SD card loaded with existing MiSTer cores and required files. You’ll have to find ROMs on your own. In order to run some of the more demanding cores, like the one for Neo Geo, your MiSTer will also need a 128MB SDRAM card, which runs around $US60 ($81).

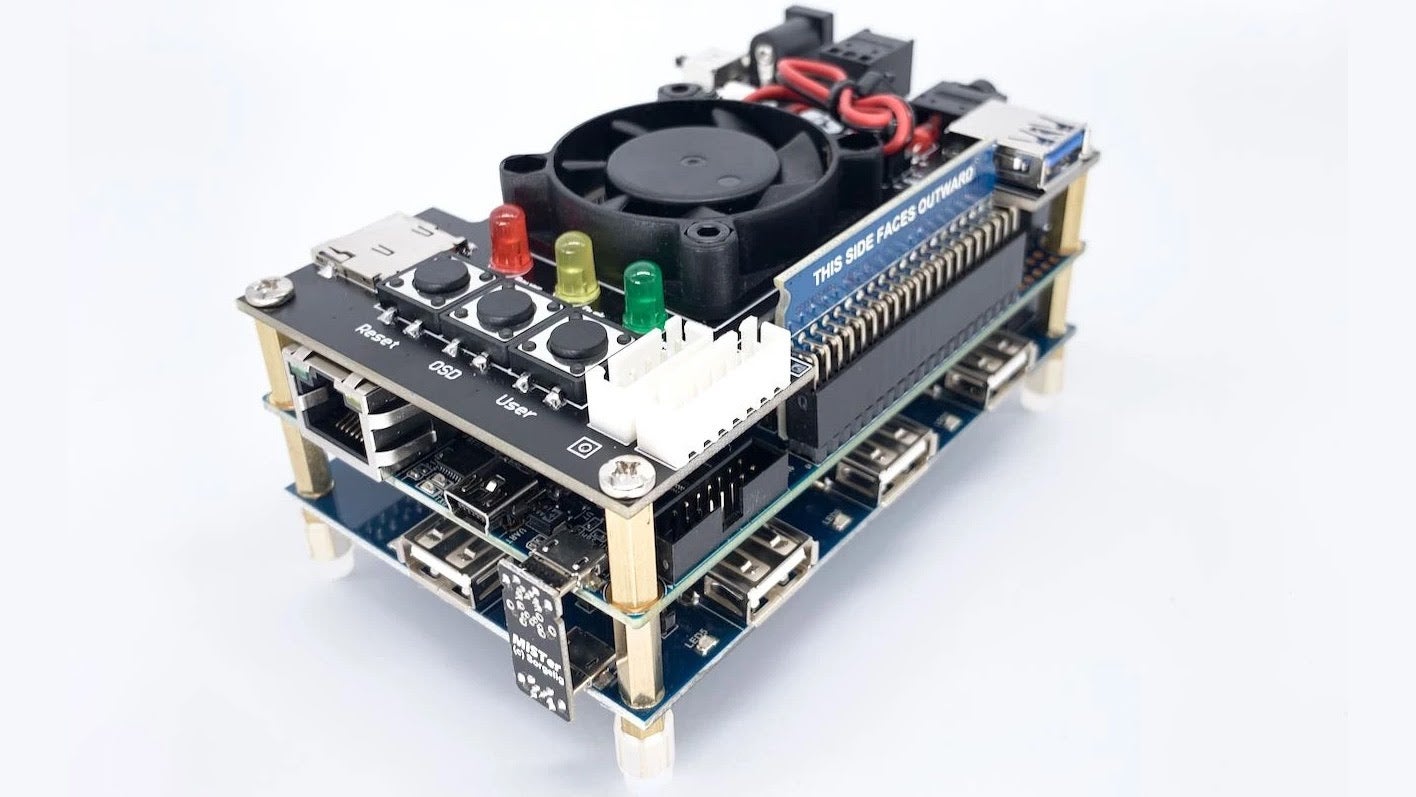

On top of the DE10-Nano goes a $US50 ($68) I/O board, which comes standard with a heatsink and cooling fan. This board features reset, on-screen display, and one assignable button, an additional SD card slot, a 3.5mm audio jack, and an analogue VGA output for when you want to hook up your old computer monitor or, with a little more tweaking, a classic CRT TV.

Completing a typical MiSTer sandwich on the bottom of the stack is a $US50 ($68) USB hub board, useful if you want to more easily plug in controllers, keyboards, Wi-Fi dongles and the like (note the main board also has a wired network port). Put them all together, and they look something like this.

If this all sounds too complicated, it’s really not. But just in case, MiSTer Addons sells preconfigured sets for $US370 ($500). Being a brave, tool-handy guy, I went for the prebuilt one, because I know my limits.

As much fun as it is to have expensive naked circuit boards sitting on your desk, there are several options for cases that make the MiSTer feel a little safer. For a while I ran mine with a simple acrylic top and bottom I found on Etsy.

Since then I’ve upgraded to one of MiSTer Addons’ $US70 ($95) passively cooled aluminium cases. The colour I picked was gold, and not “light dirt” as my editor suggested. Ironically, cramming my stack of I/O cards into the new case required a whole lot of tinkering. I had to remove the fan and heat sink from the main I/O board, unstack everything, and then put it back together. The little lights on the case? Those are small bits of transparent plastic that need to be pressed into the holes by hand. Assembling it all was the most fun I’ve ever had dropping tiny pieces of plastic all over the floor.

These aluminium cases are wonderful and secure. They can also be hard to find. If you’re interested, follow @MisterAddons on Twitter to see when they’ll be restocked next. You can get by perfectly fine using the MiSTer caseless, but it doesn’t look nearly as cool and impressive when it’s naked, and it’s more at risk of electrostatic shock or Mountain Dew.

Nice box, your editor’s an arse. So now that it’s assembled, what does the MiSTer…do?

Why, it simulates video game and computer hardware, in case that wasn’t perfectly clear. Using the default configuration, either included with your kit or found as SD disk image files on the interwebs, the MiSTer comes with a wide array of computer and console cores built right in.

To be completely honest, I was initially terrified that I was going to screw all of this up. It took me a good week after receiving the MiSTer kit before I plugged it in and started messing around. Once I hooked it up to HDMI, plugged in a USB controller, and connected it to my network, it was actually quite simple to get running. I felt like an idiot, but a very happy retro-gaming idiot.

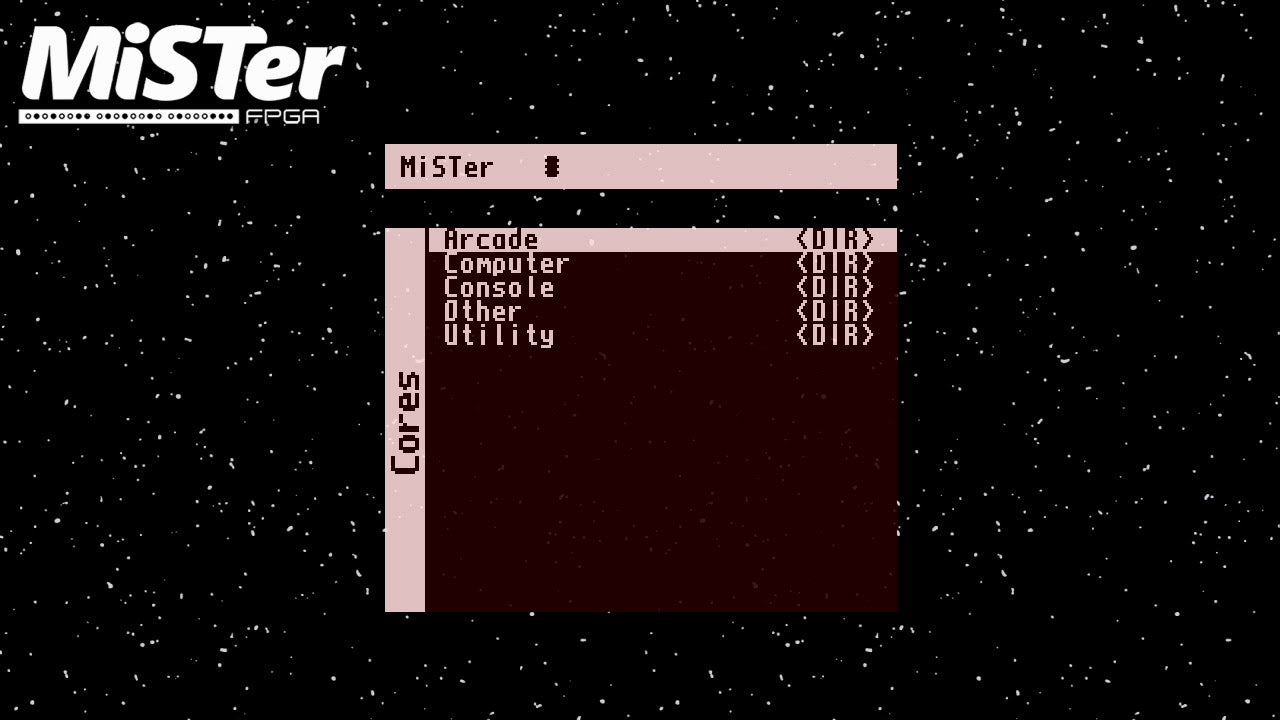

A few easy-to-use scripts make getting the MiSTer up and running simple. If you buy a kit with a preloaded SD card, all you need to do is turn it on and run the update script to retrieve the latest cores and updates. It’s best to do this with a wired network connection, as my MiSTer has been a little finicky when it comes to USB Wi-Fi adapters. Once the updates finish, you get a screen that looks like this.

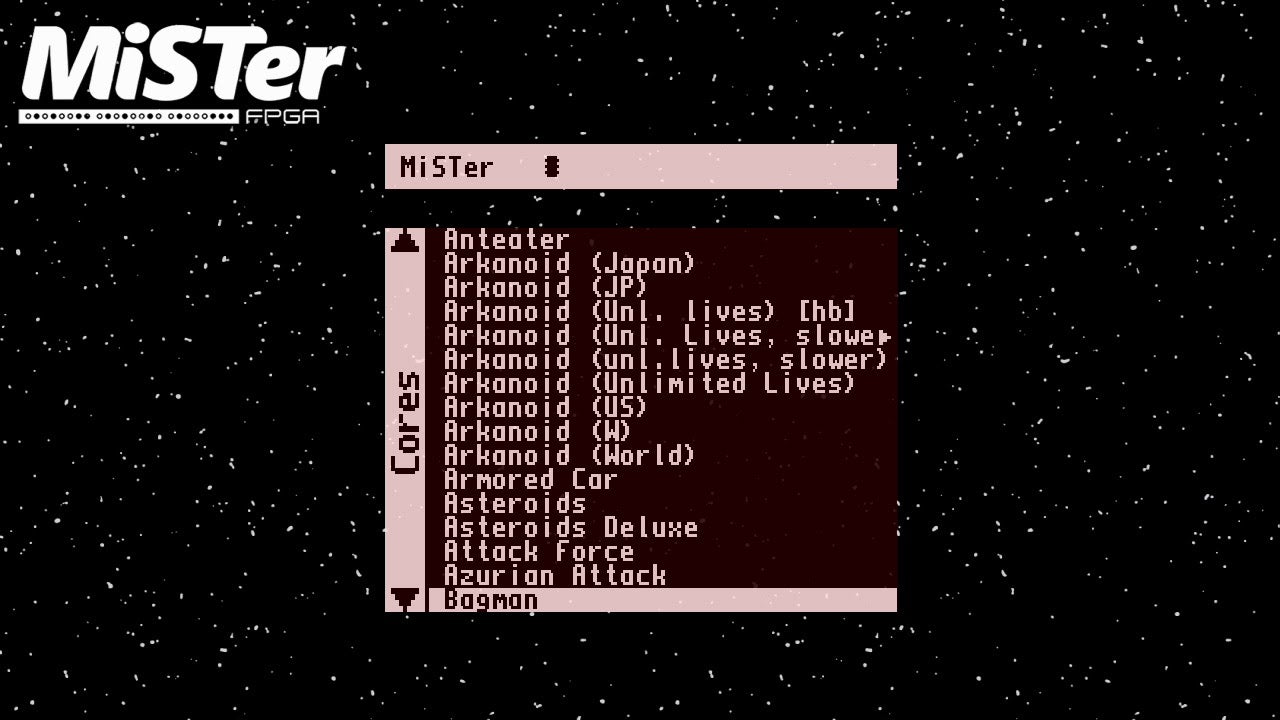

Under “Console” and “Computer” you’ll find a list of different console and computer formats. Finding games for these systems is up to you, due to the legal issues surrounding game ROMs. The “Arcade” menu, however, gets fully loaded once you run the “update_all” script, which you can download from GitHub.

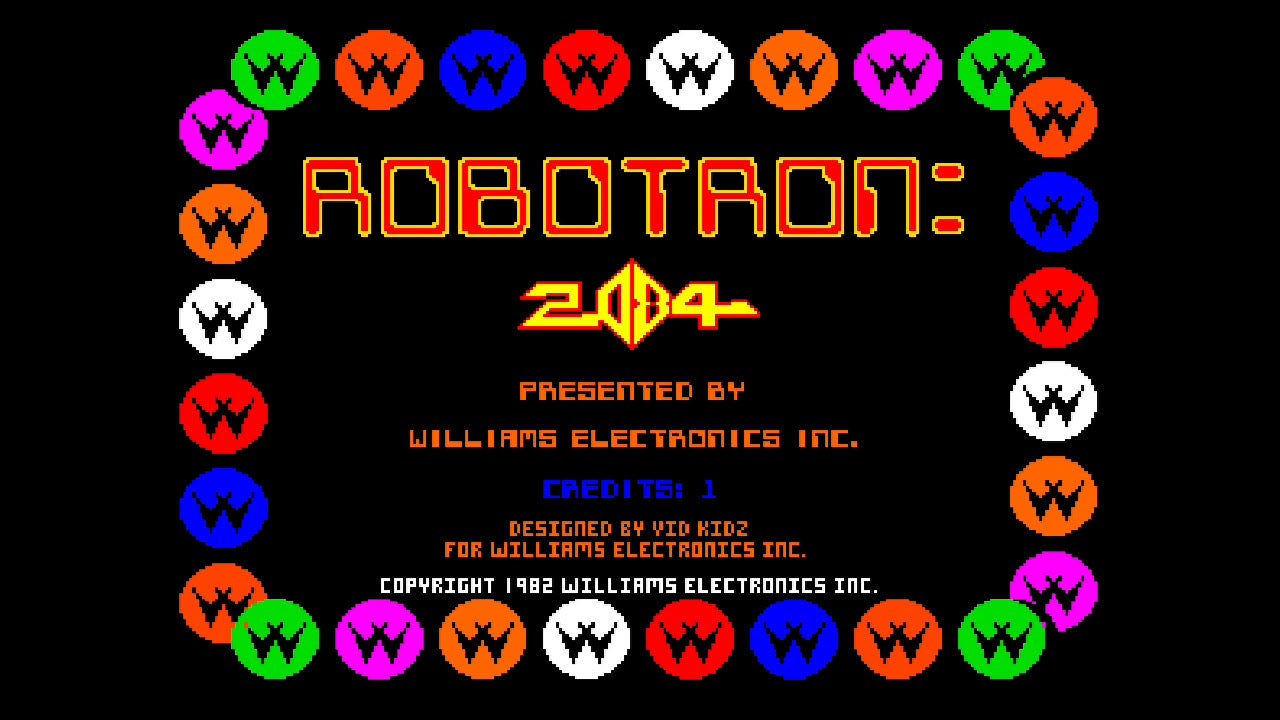

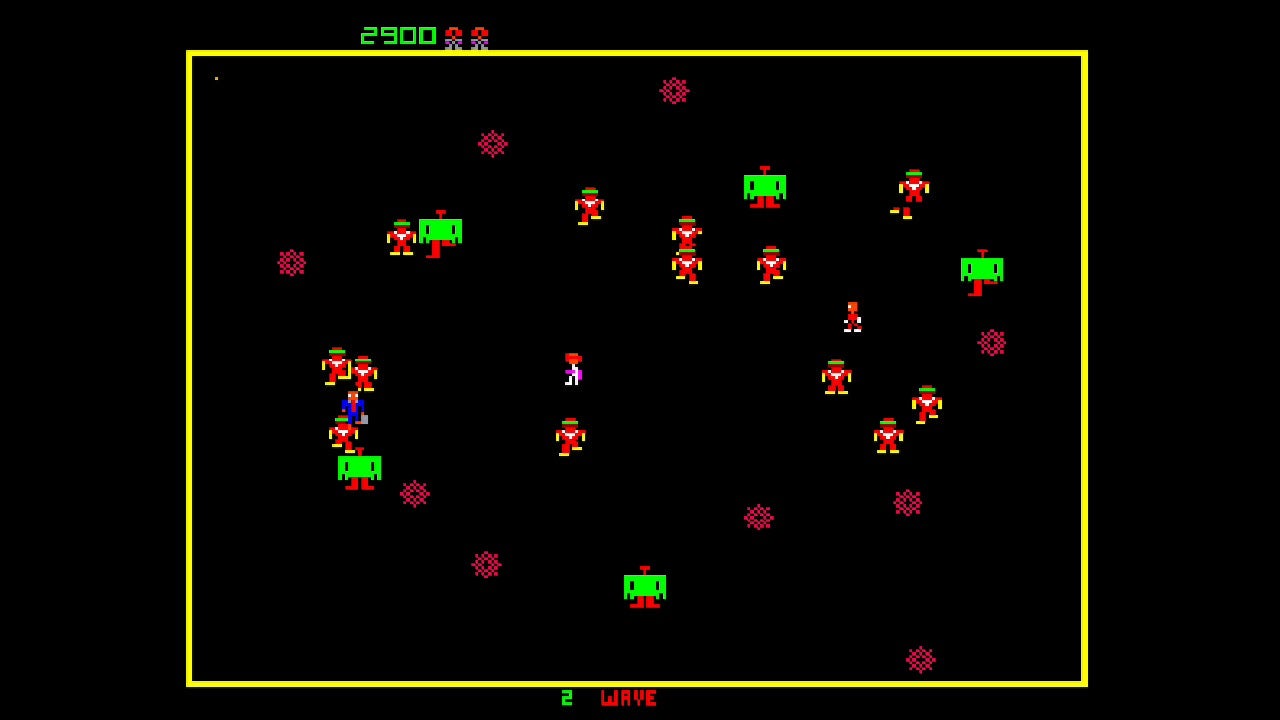

The Arcade menu populates itself with hundreds of arcade classics, from 1942 to Zaxxon. The first game I tested with the MiSTer when I acquired mine earlier this year was Williams’ classic shooter Robotron 2084. The game loads the same way the old arcade cabinet starts up, because as far as the game knows that’s exactly what it is running on.

This screenshot is upscaled, but the MiSTer has the ability to capture onboard screenshots that are the exact same resolution as the original hardware. The game looks and sounds just as I remember it. Better, even, given that the sound is being piped through high-fidelity speakers rather than beat-up junkers in smoke-choked arcades.

The visuals are bright, vibrant, and accurate. I can play at the original aspect ratio, or I can stretch out the display and apply filters. I can even remap the buttons on the Xbox One controller I’m using. There are a ton of audio and screen filters to play with, should I so choose, or I can play as close to the original arcade experience as possible. For arcade games that originally ran on vertical screens, there’s of course an option to rotate your display.

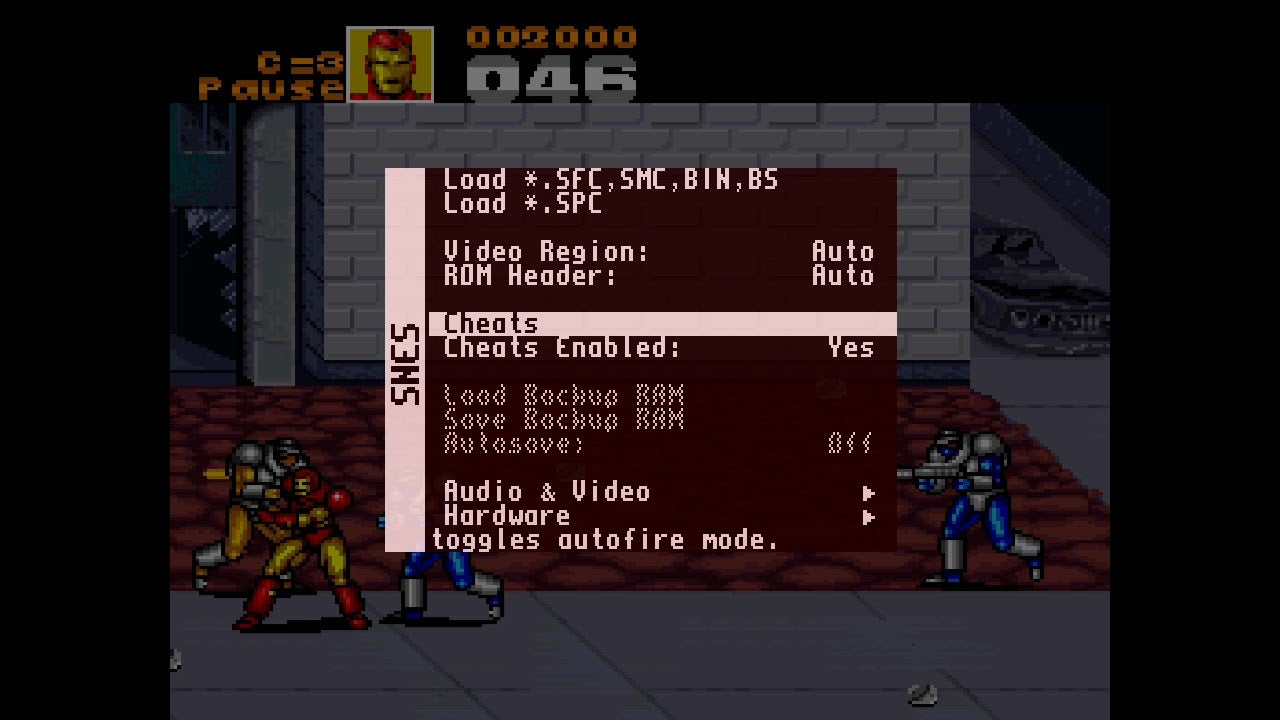

Aside from the extra step of loading the required ROMs onto the MiSTer via USB stick or (if you wanna play it old-school) an FTP program, playing console or computer games is just as easy. How about some Captain America and the Avengers for Super Nintendo?

There it is, in all of its glory. Hook it up to an old 4:3 VGA monitor or CRT to get rid of those black bars, or betray the game’s visual integrity and stretch it out wide. You want cheats? It’s got cheats.

The MiSTer features plenty of options for tweaking visuals and gameplay, but where it excels is staying faithful to the original experiences. In most cases it’s as close as you can get to playing on original hardware without forking out cash for a retro console, computer, or arcade cabinet. YouTuber Video Game Esoterica put together a wonderful video showing off the small but significant differences between simulating old hardware on the MiSTer and using traditional software emulation. While software emulation can muffle sound, drop frames, or mute colours, the MiSTer hardware — assuming a bug-free core is loaded — keeps everything running smoothly and looking and sounding great.

What games can the MiSTer play?

The MiSTer can play a hell of a lot of games. Along with hundreds of arcade games, it can also currently handle every major game console through the 16-bit era and a wide variety of older personal computers. Here’s the current list, taken from my very own MiSTer.

- Bally Astrocade

- Atari 2600

- Atari 5200

- Atari 7800

- Atari Lynx

- AY-3-8500

- ColecoVision

- Gameboy

- Gameboy Advance

- Genesis / Mega Drive

- Mega CD

- Neo-Geo

- NES / Famicom

- Odyssey²

- Sega Master System and Game Gear

- SNES / Super Famicom

- TurboGrafx-16 / PC Engine / SuperGrafx

- Vectrex

- WonderSwan

Plus a metric shitload of old computers. A few of the more popular ones include Apple II, ZX Spectrum, Atari 800, Commodore 64, Atari ST, Amiga 500, Mac Plus, and Sharp X68000. But seriously, there are dozens more.

I say “current” list, because the MiSTer is an ever-evolving project with a growing fanbase keen to get as much hardware running on their shiny little boxes as possible. Cores for the original PlayStation, Capcom’s CPS2 arcade hardware, and the Sega Saturn, among others, are in the works. Programmers are also using the hardware to expand emulation in new directions, like Robert Peip’s custom two-player Game Boy cores, which allow two players to play at the same time using a single MiSTer.

Is the MiSTer really the future of retro gaming?

No, the MiSTer is the right-damn-now of retro gaming. By many metrics, FPGA hardware simulation surpassed software emulation a few years back. And as much as I love Analogue’s FPGA-based retro consoles, why pay a couple of hundred bucks for one of those when a MiSTer plays games just as well from several dozen game platforms?

Thanks to limitations of the DE10-nano board, the MiSTer in its current state will probably hit its limit around the 32-bit generation; we’ll see how those PlayStation and Saturn cores shape up. (There’s even a little hope for N64.) But future mass-produced FPGA boards, with enough logic elements to simulate even more complex systems, will likely stretch the MiSTer’s power even further.

The MiSTer gives me all the retro gaming action I need, literally in the palm of my hand. Though that case can get kind of hot, maybe just set it on your desk instead.

Leave a Reply