Eastward is a phenomenally constructed video game. All of its music hits. The ceastharacters are relentlessly charming. Its art and level design are nothing short of extraordinary. Disregarding a few pacing missteps, the game fires on all cylinders for its entire duration. Hell, they even put a second video game in the damn thing. But I cannot help but leave it feeling strange. I think Eastward’s heart is very big, but deeply misguided. I don’t really know what to do with that.

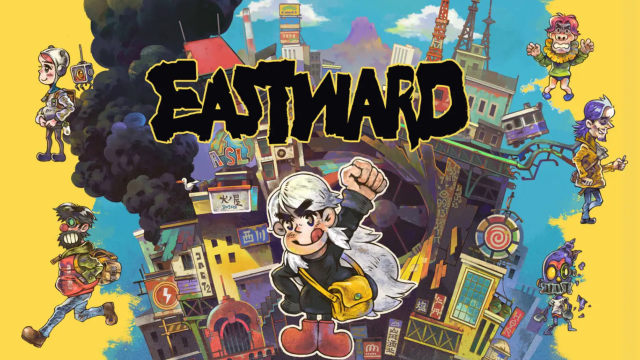

Developed by Pixpil and published by Chucklefish, Eastward is a love letter to EarthBound and classic Legend of Zelda games. It does not just wear these influences on its sleeve, but makes an entire shirt out of them. This is a top-down 2D action-adventure game with a playable, turn-based, item-heavy RPG called EarthBorn that you can optionally choose to play. There are keys of Courage, Wisdom, and Power, which you use to unlock a big door. There is a prophecy, the art of which so clearly resembles the Breath of the Wild 2 wall painting that it could feel almost plagiaristic if it wasn’t done so damn well.

I have no strong feelings about EarthBound, which I’ve never played, or early Legend of Zelda games, which I have. A Link to the Past is great! But it did not mark my heart like it did for many people, which is why I wanted to play Eastward. I wanted to experience the game as an effort of translation — a thing that turns the developer’s love for these games into something touchable and raw. By this metric, it’s a brilliant translation.

The game opens in a small, subterranean town called Potrock Isle, a town populated by a handful of miners and farmers, and ruled by a villainous and power-hungry mayor. It’s a place of poverty, but also small joys: cheap meals cooked well, standing outside your house and talking to someone for longer than you probably should, the intimacy of enduring shared shittiness. The whole place packs so much life and character into its six or so screens. Everyone is strange, and most are loving. It feels good to be there, even if it isn’t a great place to live.

You leave Potrock Isle relatively quickly, after unknowingly starting a quest to save the world, which makes all of this even more impressive. Each of the game’s four — maybe five depending on how you count the monkey train — major areas are similarly well realised. There are fun, hopeful weirdos in all of them, which makes Eastward feel like such a warm game.

This warmth extends to the game’s central relationship between co-protagonists Sam and John, whose relationship drives the game forward. Sam is a charming, excitable, magical young girl with white hair. John is her silent, strong friend and father figure. Sam is curious and wants to do things, and John facilitates that curiosity by being a great cook with a knack for violence. When Sam’s curiosity sends her off into danger, John chases after, inevitably ending up in some kind of dungeon. The two reconnect, and their two complementary skill sets get them out of whatever the situation may be.

John has access to an arsenal of weapons and bombs, most notably his signature frying pan. He wacks, blasts, and blows up basically everything in front of him. He’s a machine made for hitting, which is why he was a good miner, and potcrab farmer, and blimpig rancher, and action movie star (John takes on a lot of jobs). He’s great at killing things, but without a really reliable AOE or stun ability, extremely mobile enemies are a challenge, which is where Sam comes in.

Sam has more supportive abilities. Her primary attack is a ranged stun, which sets enemies up for a brutal John beatdown. She also has an AOE stun, and two additional support abilities which you can find by exploring. She can’t defeat enemies on her own, but she can evade them, which makes her ok without John, but easily overwhelmed.

The two of them make a great pair, which the game takes full advantage of by constantly asking you to switch between them during puzzles and combat encounters. Even more impressive is the fact that each of their unique abilities leave them with interesting things to do when separated as well. John-only puzzles still feel engaging, and the same goes for Sam’s. Instead of over-relying on switching characters for its complexity, the game thankfully distributes its depth evenly throughout.

[review heading=”Eastward” image=”https://www.gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2021/09/28/7e40d637015888fe6f39eaef6b98d4b3.jpg” label1=”Back of the box quote” description1=”For people who want to season their cast iron with monster blood.” label2=”Type of game” description2=”Top-down action-rpg” label3=”Liked:” description3=”Great puzzle design, gorgeous art, likeable characters, big heart, sense of place, and they put another video game inside the video game.” label4=”Disliked:” description4=”Predictable A-plot, slight pacing issues, its treatment of fat people, burying of The Homosexuals, and a couple of fights that just went on way too long.” label5=”Developer” description5=”Pixpil” label6=”Platforms” description6=”Switch, PC” label7=”Release Date” description7=”September 16, 2021″ label8=”Played” description8=”Completed the story in around 22 hours, but most playthroughs I’ve seen came in at 30-40.” ]

Like I said, this is a beautifully constructed game. But something has been bothering me. A couple of things, actually.

Eastward seems to have some pretty uncomfortable feelings around bodies. Fat people are one of two things: villains or punchlines. The game’s first mayor does not walk, but trundles. He is slow and hulking and greedy. In a town of starving people, he is the one who eats. His fatness is how you know he’s evil. The game’s second mayor is similarly fat, old, and frequently caught sleeping. He is kind, sure, but everything about him is played for laughs.

These depictions extend throughout the game. If a character’s body looks weird, they will be a different kind of strange from the characters around them. Everyone in Eastward is odd, which is what makes the game charming, but so frequently fatness is treated as the odd thing in and of itself, and not just part of the person.

The game has similar feelings around queer-coded men. To give an example from the late-game, there are a few maids with beards trying to advertise a bakery by yelling at people on the street, and instead of Eastward treating this as the setup for its jokes, it uses them as punchlines in and of themselves, which is disappointing. Playing with gendered performance and expectations can be, and often is, incredibly funny, but Eastward’s deployment of queerness feels punitive and frequently disgusted.

And wow is it horny sometimes. When I first saw Eastward I did not expect to get pixel jiggle physics multiple times.

But to explain why Eastward, and all of its depictions of non-normative bodies and queerness, is sitting so strangely within me, I actually have to talk about parts of the plot in detail. Consider this your spoiler warning.

The 1984 film Paris, Texas, has, through its first half, a nearly silent protagonist named Travis. He has been drifting for the last four years in a dissociative haze. The film opens on him stumbling through the desert, ultimately collapsing. He awakes in a bar, and refuses to speak. His brother finds him, and takes him home. There he meets his son, whom his brother adopted, and who loves him very much. It’s a movie about love, violence, and masculinity, and I couldn’t stop thinking about it while I played Eastward.

John is never shown speaking on screen. He is implied to speak at a handful of points, but there is never a textbox that starts “JOHN.” He is a quiet man, and built for violence. He never tells Sam he loves her. I don’t know if he can.

John’s love is, instead, all about service: protection, violence, and cooking. He keeps a roof over her head, carries her when she’s tired, and tears apart anything that comes anywhere near her. His love is framed as pure, fatherly, and correctly masculine.

At the end of the game’s final chapter, Sam sacrifices herself to save the world. John is left emotionally broken on the ground. He continues doing what he has done throughout the game’s entire duration, and does not speak.

There are two other central relationships in Eastward, between a man named William and his robotic son Daniel, and of a lesbian couple named Isabel and Alva. Each of these relationships also end with a heroic sacrifice.

William is framed as a scamming arsehole throughout. You meet his biological son, also named Daniel, in Potrock Isle. He was abandoned by his father a long time ago. William uses his robot son to scam people, including John and Sam. The dude sucks. But in the game’s seventh chapter he reveals that he’s done all of this to get the money and resources to acquire an emotion chip for his robotic son, because the boy wants to feel. Daniel, after acquiring the chip in a successful operation, heroically sacrifices himself for William and the game’s protagonists. William collapses on the floor, and tells John to do what he could not, and protect his child Sam. John then goes off to do violence while William sits in shock.

Alva, meanwhile, is a kind scientist, and the constitutional monarch of New Dam City, a role which she does not often embody outside of its title. She’s trying to find a way to save the world. Her partner Isabel is referred to as a muzzled dog. The two met when they were children, after Alva’s grandfather found Isabel in a machine deep within an abandoned complex. Upon meeting Alva, Isabel became violently protective of the other girl. When Alva’s brother’s dog excitedly ran to meet Alva, Isabel cut it cleanly in half in a misguided attempt to protect Alva. She then wept at its funeral.

During a climactic scene, Alva walks into a monster-filled reactor, unarmed, to perform a manual override of the power system. She succeeds, but is left comatose. This breaks Isabel, who then tries to save her life and also to get revenge. She almost murders the sleeping Sam — blaming her for Alva’s condition — but stops at the last moment.

You find her in the game’s final dungeon, attempting to clone Alva to bring her back to life and risking the world in the process. Her obsessive love is framed as disgusting and wrong, and John’s as pure and good. The game then makes this mechanically explicit, by forcing you to fight her. You can’t attack Isabel, only parry her blows, and then knock her away. This slowly exhausts her and eventually she admits defeat. The ghost of Alva begs her to give up and move on.

Isabel walks off screen and is never seen again. Eastward and its world have no place for her.

The game’s epilogue sees William rebuild his relationship with his biological son, just as robo-Daniel’s eyes light back up for the first time following some successful repairs. The three of them live happily ever after.

John, while drifting, sits alone at a train station. Behind him, a city lies drowned in the water. Buildings poking above the surface, as heat waves distort the concrete around him. A white-haired girl who resembles Sam passes by, alone. She’s implied to be some kind of reincarnation. He stands, and resumes his service. The game imagines him happy, too.

Eastward has a bit of a double standard around Isabel. Her love is violent, obsessive, and singular like John’s. She would do anything — including putting others at risk — for Alva, like William does for Daniel. And yet, it is so clearly uncomfortable with her. She is never able to really express her feelings for Alva in language, despite speaking. She is literally referred to as a muzzled dog. She is a machine built for violence, and everyone who comes into contact with her excluding Sam, John, and Alva, is terrified. There is a tragic wrongness to her love.

In the second-to-last scene of Paris, Texas, the film’s protagonist Travis sits across from his ex-wife in a phone sex booth, and asks if he can tell her a story. Unaware of who she is speaking to, she says yes. Travis has remained quiet through most of the film. Here, however, the flood gates open.

He tells a long and brutal story about an older man who loves a younger woman very much. The man’s love turns to a violent, controlling possession. As he tells the story and incorporates more specific details, the woman realises who she is talking to. Travis reveals that he chained his wife to the stove, while their infant son wept, and left to drink. He nearly killed her several times, so she fled. It broke him, and set him adrift for four years. It’s an ugly story.

At its conclusion, he tells her that her son is waiting for her in a hotel room, and leaves. He knows that he can’t be in her life, but still wants to rebuild his family. The only way to do that is without him.

The film is a quiet meditation on family, masculinity, and power. I think about its ending almost every day: the idea that love can be both real and destructive, and that navigating that reality sometimes means walking away so you stop hurting people. The film both interrogates masculinity, and wholeheartedly believes it can be something else that is redemptive and worthwhile, even if its protagonist cannot embody that on account of his prior mistakes.

John and William are offered a reconstruction without real sacrifice, and without having to compromise the ways they interact with the world. John remains a silent man who’s good at violence, and William is still a charming con artist, albeit a stationary one. Their families are happy.

Eastward never offers this to Isabel, never even offers the compromised kind of love that Paris, Texas allows Travis to embody. There is no reconstruction or redemption for her like there is for John and William. There is no interrogation of the relationship between Sam and John, nor of that between William and his sons. They are left unquestioned, while Isabel is put under a microscope constantly.

Eastward is playing with the imagery of silence, love, and power, but rarely does anything real with them. The relationship between John and Sam is sweet, but feels predetermined; it’s an uncomplicated love, and utterly frictionless. John’s love for Sam is good and masculine, and ultimately saves the world. Isabel’s is othered and strange, and nearly ends it.

She just fails, and then fades away like the ghost of her lover. And she deserved better.

Every othered character in Eastward does, really. For a game that loves strangeness, it only extends that love to a certain kind of strange person who is harmless and normative, who looks and acts the right kind of weird. Sure, it has a big heart. I just wish it was bigger, and that its teeth were sharper.

Leave a Reply