Confiscated emails. Sinking ships. The looming feeling that layoffs are coming, and there’s nothing you can do to save yourself. Two weeks ago, we took an extensive look at why there are so many layoffs in the world of video game development. Since then, hundreds of developers have reached out to sympathise, and to share their own anecdotes and stories.

We offered many of those developers — who spoke anonymously in order to protect their careers — the opportunity to share their own stories of game development layoffs, and perhaps help push for some change.

(Got a story you’d like to share about working in the video game industry? Reach out. All correspondence will be kept anonymous.)

There are thousands of these stories. Here are a few.

Birthday present

I worked in the level design field at [REDACTED].

Last year on a Friday, a phone call woke me up. It was my girlfriend congratulating me on my birthday. Happily I went to work looking forward to continue working on our new project and later go out for birthday drinks.

When I arrived, the suits gathered us all in a conference room and told us our project, along with more or less the entire studio was going to shut down.

Most of the long time employees got moved over to [REDACTED]. Me and the rest of the contractors though, were on our own. What made matters even worse is that the publisher archived all the work we had put into the project which resulted in nothing to show in our portfolios during the inevitable job search.

This has left me with a foul taste in my mouth regarding the entire AAA industry. After I’ve finished studying programming, I’ll probably pursue a position at a much smaller, more humane studio or another field entirely.

The merger

A major layoff occurred at Radical after Vivendi Universal merged with Activision, in 2008, and it is public knowledge that about 100 people were laid off. It was a strange merger in that I heard Vivendi acquired Activision but put most of Activision’s management in charge.

At the time, Radical had almost an entire floor dedicated as a huge recreation hall. The hall included arcade machines, a ping pong table, a kitchen, a living room with couches, a fireplace and a full size log cabin inside the room! Back then, when Radical had a company meeting and all four teams met in the hall, it was a huge crowd. And it was fun…most of the time.

We had one of those meetings to discuss the merger, but we were told nothing of substance, and no information trickled down to us. I was not able to determine whether Radical management did in fact have any information of value. The corporate message was that the merge had to be a positive thing.

Some time passed, Activision sent some of their management to assess our company and a new meeting was organised. This time around it was not the CEO of Radical who did most of the speaking but a representative of Activision. This is where the news of the layoffs struck us straight out of the blue.

Management in every games company really likes to do the “sandwich” whenever they have to say something bad: they start with something positive, they give you the bad news, and then mention something good again. The “sandwich” is the most absurd communication technique ever invented by mankind and should be banned from every management book on Earth. The result is that, after a few years in the industry, every experienced game developer has a Pavlovian terror response whenever he hears good news!

In that specific meeting however, neither I nor anyone else saw it coming. The Activision representative started talking in a relaxing tone about the merger and only after a while, almost with nonchalance, the part about the cuts were mentioned vaguely. She did not say outright the words “cut” or “layoff”; what I recall is that she said that they were only going to manage two projects at Radical, and since Radical had four projects some readjustments had to be made. It seemed odd since Radical had traditionally managed four projects successfully for years. I don’t know if her explanation was the real reason or if they simply did not like two of our projects. The ones that went forward were Prototype and Crash Bandicoot.

Following that announcement, the people working on the two cut projects were sent home for what was basically a 2-3 week long paid holiday. During that time Radical had to decide who to keep and who to lay off. Radical had chosen not to lay off all the people in those two teams but instead to pick and choose from their entire staff. It was common opinion, however, that most of the people on the two projects that were kept would be safe. The layoff news must have reached Radical’s management rather suddenly if they had to take their time to organise the layoff. Also, Radical had just recently gone on a hiring spree, hiring people from all over the world and relocating them to Vancouver — which is a rather expensive undertaking.

The merger was probably an extraordinary case, since usually a layoff is not announced until all decisions are made. I can only guess that with many layoffs happening in several of their studios, the rumours would have spread. To their credit, I think being upfront was a good decision.

People with mortgages and children started to worry, realising that when the layoff came, over 100 people would be unemployed all at the same time, and the job market in Vancouver would suddenly be over-saturated. It helped that Vancouver was a big gaming city so those laid off might not have to relocate. When the layoffs occurred, with the involvement of Radical, the other companies in town hosted recruitment parties for the suddenly unemployed.

Looking back, there is a certain amount of involuntary black comedy in the layoff event. Usually everybody gathers in the meeting room just to be told to go back to their computers and wait for an email telling them what room to go to. At that point you can look at people frantically clicking on the “get mail” button on their email client. And there is always someone that does not receive his email and does not know who to ask since HR is scattered all over the building.

Up to that point Radical was ranked as one of the best workplaces in Canada and for good reasons. It wasn’t just the salaries and huge recreation areas. People in HR and management positions really cared for the employees and you could tell they meant it. So, while the experience was indeed traumatic for many, Radical did a great job at handling it given the circumstances. And the frustration wasn’t just on the faces of the people leaving but also of those staying and of those making the decisions. Unless a layoff is made to cull unproductive people, it is perceived by management as a personal failure, and they won’t be happy about that either. In fact, Radical went the extra step to try and get everybody employed elsewhere. In all those things, they did a great job.

The things that were not managed well in my opinion were transparency on the selection process — as well as the selection process itself. In a large company, some mistakes regarding who to keep and who to layoff are unavoidable, but some of these mistakes may also be a symptom of too many layers of management and politics. This is not restricted to the Radical layoff. I’ve seen really talented people laid off while the good talkers are kept — in my experience, at big companies it’s rare for the right people to be asked who should stay.

At Radical, I never found out who made those decisions. If I fail a job interview, I can pick up the phone and, by being gentle and pushy at the same time, I can get them to tell me what I was missing, why I was not the right candidate. This critique process is extremely useful to improve yourself when the next job starts. In a layoff, you’ll never get that feedback. The risk of a law suit is too great, so you’ll never know why you were laid off or who made the decision. Years later, at a completely different company and completely different layoff I enquired why certain very talented people were let go and hit the same brick wall.

The three-day wait

The studio at one point was a 1.5 team, one main console team, and a secondary, smaller team focused on smaller (and interestingly, all profitable projects). As the larger console game was ramping up, the smaller team was merged in, claiming that it was a temporary resource commitment. A few of the more senior guys saw what’s up, and pretty quickly decided it was a sinking ship soon and bailed (and for us on that smaller team, having seen where the other project was heading, wasn’t too happy about join gin either). Those were the lucky ones.

Project chugged along, occasionally crammed with all sorts of dev issues, like complete change of scope, reworking of entire systems (mandated by people we’ve never seen before), rushes for demos, and extended crunch for months. At one point, one exec had casually mentioned that if this game isn’t successful, “maybe the studio won’t make it”.

A month before hitting the gold master, people were starting to get worried; there was absolutely no talk of new projects. And suddenly, a new manager was brought in from HQ. He was tasked with “helping the team finish”, but it was very clear soon that he was essentially the closer, brought in to do the firing.

When the announcement came, it wasn’t a “you’re all fired”, but rather they said they will be downsizing and rescoping the team to focus on different platforms (Facebook and mobile). So we sat around, waiting.

It was a three day process, and perhaps the most surreal thing I’ve ever seen in a firing process: employees were called in one by one, but it wasn’t clear what the order was. It’s not by rank, or by alphabetical. And then we find that the first batch were given a pass to stay in the office. Then suddenly, another batch was called up, which were to be let go. Eventually, we realised that they were doing a draft like setup: talk to the people who would like to keep, and once they have certain employees locked down, they began cutting people out who they need to trim the headcount on.

Unfortunately, for the majority of us in the middle of the pack, it was a nerve-racking 3 day wait to find out if we still had a job. (One guy was so fed up that in the 3rd day, when they finally talked to him to offer him the job, he straight up told them no, even if he had nothing lined up).

While that was a crazy experience, what’s crazier was that we were kept around the office for another month and a half (because of how the pay had worked out), and that we were still needed to test the gold master disk. While we were still on payroll, we were essentially un-firable at the point, and some people clearly didn’t give a shit anymore so they just came in to the office, played games all day and left. Meanwhile, others who were given an extension to their job was sitting next desk and still working hard.

Two weeks a month

I have a little story from a small game company called [REDACTED] in Beijing.

This is not your normal game studio, oh no. It’s been around for about 4 years now, but it has not released any games! Not a thing, no revenue coming in at all from their business practices (but a fair amount coming in via corruption within the Chinese government…)

So we were working away on a game for a couple of years, but the release date kept getting pushed back… March 2013…May 2013…September 2013…March 2014…but no progress was made on the game at all since February 2013

The reason for this? Simple really, people weren’t getting paid. We were due to get paid on the 10th of every month, but every month the 10th would roll past with no sign of the cash. At best, we’d get it by the 24th (which always confused me, why not just change the payment date? -.-). This seems to have been going on for a while before I joined, so as soon as the 11th came by, and people still hadn’t been paid, the entire development team would just stop working. They would sit at their desks playing WoW or LoL, refusing to contribute to the game until they were paid. This meant that every month there was at most 2 weeks of development time going into the game, which funnily enough meant that the developers were actually getting paid a full months salary for 2 weeks work (although the management never caught onto this, as they were incredibly inept). It really was quite the show of disobedience from a Chinese workforce that isn’t normally associated with strikes etc.

Anyway regarding the layoffs. So the CEO decided we no longer needed artists…any artists at all, so he took all 17 of them into his office. There he told them they are all fired, and that they must sign the form on his desk to say that they accept the mutual termination of their contract and are due no severance pay. Now this may have worked if he did it 1 on 1, with a bit of intimidation from his powerful parents, however when there are 17 people in the room? The artists burst out in hysterical laughter and told him there is no fucking way any of them are signing that shit. They then all went to a nearby law firm, got themselves an employment lawyer and sued the company. I’m no longer there, but I hear they got quite a nice payout, 3-4x what they would have been owed in severance.

And the icing on the cake? Well the CEO and his mistress decided its about time they actually looked at the game that their company was making. What they saw was pretty much an interactive novel, with CGI clips and very little interaction. Sure enough, the game was scrapped and people began leaving in droves.

Paid too much

In Sep 2011, I was working for a games company in the UK in their London office. I’d transferred there as it was closer to my home rather than their other studios. I got the same letter as the game team developing XXX – I was being made redundant. Even though I didn’t work for the XXX team, the whole studio was being shutdown.

I’d guess something was going to change, but this was a complete surprise. Other industries I’ve worked in handle this better – by reducing the number of people but not by closing a site.

We then found all our equipment was removed, and access to their other studio restricted. Suddenly I couldn’t do my job as I was locked out. Eventually, grudgingly it seemed they gave me access.

I remember going to a meeting with my boss in the other studio to find my card key wouldn’t let me in. Eventually he had to come out to let me in, I felt I should be wearing an “NOT WANTED HERE” sign or something.

It was bad enough the doors were locked before 9am and after 5.30pm – luckily a security guard hadn’t been told what was going on and let us in (or out!) anyway.

We had several agencies allowed in to help us find other jobs. Also the guys at the London studio tried to create a new studio but sadly the doors closed in late 2011.

Worse was to come. We got paid redundancy but they’d made a mistake. They paid us too much. Instead of writing and politely asking us for a return, we all got threatening letters with deadlines quoted that were impractical. I paid back what I owed as I’m already sitting on a pot of money from other redundancies, however others were not so lucky (as has been written elsewhere).

Reject the promotion

Just read your article about developer layoffs and thought I’d add my 2 cents.

There are worse practices than what you’ve described. One such practice is the play between hourly wages and salary wages. Often companies will go into crunch-time, and right before they would move their hourly employees to salary. This means they don’t have to pay OT for those people, which by law is x1.5 their hourly wage, since they now make a flat wage. When crunch ends, those folks are “let go,” often to be rehired again a couple of months later, on an hourly wage of course. I have personally recommended new people at my old company to flat-out reject the “promotion,” knowing full well that it will cost my superiors more money by doing so.

This leads to another issue. That some people are valuable enough to demand a higher non-hourly salary, which legally would include benefits, from the get-go. I have managed to get that at my last job. These people are more protected from the layoffs cycle, though not entirely of course. This creates two classes of developers. The permanent one and what I call the disposable one.

This skews the numbers a bit. For instance, you gave a roughly ~80k average salary. I’m absolutely certain that’s not true, at least not for the disposable developers. That number must include the more permanent ones, but those aren’t in as much risk of getting let go. So that number that you calculated at ~800k savings is in reality much lower.

And me personally, after 4 years in the industry, a lead position, and having worked on some major titles, I have left the industry for another career precisely because of these reasons. And many more actually. There are quite a bit of shady practices out there that I haven’t seen mentioned.

Like cows to the slaughterhouse

On a hot summer morning in August, 2010, an email was sent out a little after 10am (our flex-hours required us to be in by then at the latest,) saying a company-wide meeting would occur at 11:30. Myself any my team members didn’t think too much about it at the time, but in hindsight I could feel tension among some of the upper-ranking developers.

When the time came, all of the Senior Producers went room-to-room, ushering developer after developer into our motion-capture area, stating that this was a required meeting. Being the cheeky bunch we were, many of us made jokes about how it’s a surprise party with beer, while others (like myself,) joked about layoffs and using a paintball gun as a deciding mechanism. That was a stupid comment to make.

After the studio was quickly herded into the large room, the large doors were slid shut behind us, reminding me of cows being herded to the entrance of the slaughterhouse. Within seconds, the Studio Director appeared with a piece of paper. His nervousness was palpable while reading from a scripted piece of paper, which he seldom did. “With a history of 8 years of no layoffs, and a consistent track record of delivering quality products on time; I’m announcing that today we will be making employment concessions in order to deal with changing expectations.” I had no idea what that meant, other than we were on the chopping block.

Of course, being in QA, I knew my fate was sealed. Along with all of the smokers, and ex-smokers, many of us headed outside for a quick stress-relieving burner. After a group of 20 or so people finished their quick cigarette, we headed back upstairs only to find that many of our badges didn’t work. They had deactivated many of our badges before even having our exit-interview. Frantically, one by one, many of us swiped our badge on the reader, the first 6 or 7 finding theirs did not work. The next person’s worked, and we were able to walk to meet our managers, head in hands.

The escort

I worked at [REDACTED] for about 6 months and decided it just wasn’t for me. I met with my lead and spoke to her about how I was ready to move on from [REDACTED] and ready to give them my two weeks. She understood and said she would just need to talk to HR/Recruiting about it. I said that was fine. I went down stairs to grab some lunch. Maybe 20 minutes later she comes down and finds me and tells me that I have to come back up stairs and place all my files on the server because they want me out now and they will be escorting me out the building.

I was pretty shocked. This was my second job in the industry out of college and it just felt very cold hearted. I went up to my desk and transferred everything over. All my co-workers were trying to figure out what was going on. I was Skyping them and telling them to meet me after for drinks haha. I was told I needed to sign some exit papers from recruiting. I went down to recruiting and had a completely opposite reaction. The person I spoke to was all happy, sorry to see me go, asked if I had enough time to get everything together. I said uhh yes? I was told I need to be out in like an hour. She’s like oh don’t worry take your time! I was so confused. But how it was initially handled made me want to leave as soon as possible.

‘I’m open to leaving the industry altogether’

Nearly a year ago, I was laid off with around 200 other devs at SOE. It surely came to a shock to me because the people I was sharing the room with were highly skilled developers like myself; not temps or part time testers. Many of us kept thinking, “They must be moving us over to a new title or something. I mean they can’t be letting go of these people, right?”

Wrong.

People who had been at the company for over a decade were being handed their pink slips. I’d managed to dodge the last few big layoffs at the company for the nine years I worked there but eventually the law of averages caught up with me. Like you mentioned in your article, many of us who were laid off suddenly had zero access to our computers. We couldn’t log into them without an IT person standing behind us and we sure as shit couldn’t take anything unless there was (in my case) an Art Director standing behind me telling which art I could and couldn’t take for my portfolio (This royally sucked by the way).

A lot of us felt numb at first and then later felt betrayed. We put all our sweat into the products this company produced and then they just cut us loose like faceless cogs in a machine- we didn’t do anything wrong; we just ended up with shitty luck that morning.

There was some news going around that the lay offs of so many long term employees was because of a financial issue. That the people who got sacked ended up on that unfortunate list because of how much they made. Who knows.

They did go above and beyond what was necessary for a company who just laid off a bunch of people. They let us go two months before the actual lay off date so that we could look for work while still being paid a salary and have benefits. They cashed out our PTO and also gave us pretty nice severance checks. They also sent out mass emails to help some of us find work.

But really, in this economy, and the challenges of facing off in a hyper-competitive industry; it was difficult for many of us veteran developers to find work.

I’m looking for work in the industry, but I’m also very open to leaving the industry altogether if I can. I can’t even start a family and plant roots because of the fear that I’m going to be jobless in the next fiscal quarter.

Big Huge Games

When people talk about the 38 Studios closure, they tend to forget that it also killed Big Huge Games as well. They had bought BHG a few years earlier, saving us from collapse after THQ dropped us, and under them we had had just released Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning. We were proud of the sleeper hit we had made against all odds, and we were very focused on what we had to improve for the next game. We were in pre-production for the next game, addressing those issues and working on a balancing patch for the base game when we found out that EA had done some restructuring, resulting in dropping our plans for a sequel. This was an amenable break, with them letting us keep all the rights, and we had other publishers who were interested in picking us up for Reckoning 2, so while it was a bit of a shift, we weren’t too worried.

So we continued working on pre-production and the re-balancing patch while management found a new publisher to work with us. A couple studios were drawing up offers. Things were going so well that as the release date for Diablo III approached, the studio declared that we’d have a “research day” — on the day Diablo III released, all employees would be encouraged to come into the office and “research other work in the industry.” After all, it was a better solution than having everyone call in sick to play at home.

It was a Tuesday, so we met for our regular Tuesday morning meeting, with breakfast catered by the deli in our building. As we were all chatting over eggs and muffins, one of my coworkers mentioned that something must be wrong with his bank, because his paycheck hadn’t gone through to his account. Another coworker said she was having the same problem, but with a different bank. Instantly, everyone was on their phones and checking their bank balance. None of us had been paid.

We immediately knew there was a problem, but we didn’t realise how big it was. When our meeting turned into an impromptu phone call to payroll at 38 Studios, they assured us that it was just a minor error and that we’d all be getting our checks immediately, once they straightened things out with their bank. Go ahead and play, we’ll have it solved and let you know at the end of the day. Curt Schilling apologized for the mistake and promised to make it up to us all.

“Start looking for a new job.” my friend said, “Right now.” But I was sure it was just a temporary mistake.

We played games, then came back for the end of day meeting. 38 Studios was having an all-company meeting to explain what had gone wrong, so we all piled in to join via webcam. There had been a clerical error, they said, and it was being fixed. Our paychecks were all printed and ready, but the bank had to fix one more thing before they could be delivered and cashed, they said. It’d be ready first thing tomorrow morning. People asked polite questions about how to avoid this in the future, or made jokes about getting time off until this was fixed.

We met again the next morning, a little less enthusiastic. There were still inconsistencies, they said. They’d have it all worked out by the evening meeting, they said. At the end of the day, they had more excuses, but promised the paychecks would be coming the next morning. The questions got a little less polite and the jokes got a little more barbed.

This happened every day that week. Curt started tearing up when he apologized to us. Then he started getting defensive and angry when he was asked questions. Eventually, he stopped talking to us at all.

We kept coming in because our team was very close, and many of us didn’t have anything else to do during the day. Few of us were getting work done, although even fewer of us had started looking for new jobs. The balancing patch had to be put on hold; it costs money to release an update to a game, and we didn’t have that. We were all sure it’d be worked out eventually.

Most of all, we were looking at what we could do to make Reckoning 2 more attractive to potential publishers. We knew that as long as we had a publisher for the sequel, we could survive, even if 38 Studios collapsed.

On Friday, BHG officially let our in-house QA department go. It was the first time we had admitted that this wasn’t going to get better, and it hit us hard because these were our friends who had worked alongside us for years. Once we had a publisher, we’d hire them all back, we promised. It’d be ok, we said. We drank with them at our desks through the day. At the end of the day, 38 Studios told us that everyone was officially on furlough until they worked things out.

That weekend was rough. None of us had been paid, and those of us who lived paycheck to paycheck were getting pretty lean, but we were hearing horror stories from up in 38 Studios that put our troubles in perspective. You’ve seen the reports, I’m sure: mortgages in foreclosure, pregnant women learning they had lost their health insurance at the doctor’s office because 38 had stopped paying it, all that sort of thing. We even learned that management had stopped paying the deli for our Tuesday breakfast meetings, running up a tab of thousands because the deli owner had known and trusted us for years. We didn’t know how to break it to him.

The next week, most of us came into work anyway. No one had shut the office and we’d spent so long together crunching for Reckoning that it was our second home — plus, most of us didn’t want to be on our own. The news out of 38 was getting more and more dire, and we were realising that they wouldn’t be coming back, so we turned all of our efforts towards getting another publisher to pick up Reckoning 2. Our official layoff emails came from 38 Studios and we barely noticed them as we prepared for visits from interested publishers. It may have been too late for 38, but Big Huge Games could survive.

Then the governor of Rhode Island started making 38’s collapse into a political issue and it became mainstream news. Politicians and bank officials quoted scary-sounding numbers about our finances out of context, and they were repeated around the world by news sources who knew nothing about the process of making games. “Amalur” became synonymous with mismanagement. The publishers who had been talking with us decided the whole situation was toxic and pulled out of talks with us.

We couldn’t blame them. We knew it was all over.

Usually, when a studio closes, a handful of people are kept employed for a while to ensure that shutdown goes smoothly: offices are closed, assets are cataloged, legal issues are settled, etc. But this closure was entirely unplanned, and we had none of that. For a week, it was chaos.

We still hadn’t been paid, and the government and the bank had first priority of getting repaid from the money that 38 no longer had, so we knew we’d never be seeing our last paychecks. People started packing up their things, saving copies of work for their portfolios, grabbing mementos from around the office. Everyone was sharing news of job offers and advice about how to sign up for unemployment. Other studios were sending people for an impromptu jobs fair at the restaurant nearby.

Some of us found jobs. Some of us quietly turned our backs on the industry forever. The drinks we had kept for special occasions were drained in countless teary-eyed toasts.

We knew that the studio’s official assets would be put up for auction (not that we’d see any of the money), but we also knew that the only assets that could be officially tracked were the things IT had tagged. Some might have called it looting, but since we were all owed thousands of dollars apiece, it seemed perfectly reasonable. Computers and monitors stayed, but everything else was fair game. The high-quality marketing toys like replica weapons and standees were divided up between our coworkers as consolation prizes for how hard they had worked. Ex-coworkers came into the office for a proper farewell. We had a mini-reunion at work. Then at the bar. Then wherever we could gather. We still do, whenever we run into each other at GDC or the like.

Eventually, we knew we had to leave the office. An outside company would be coming to catalogue its assets and move everything into storage. So we packed up the last of what we could salvage and turned out the lights as we all went our different ways.

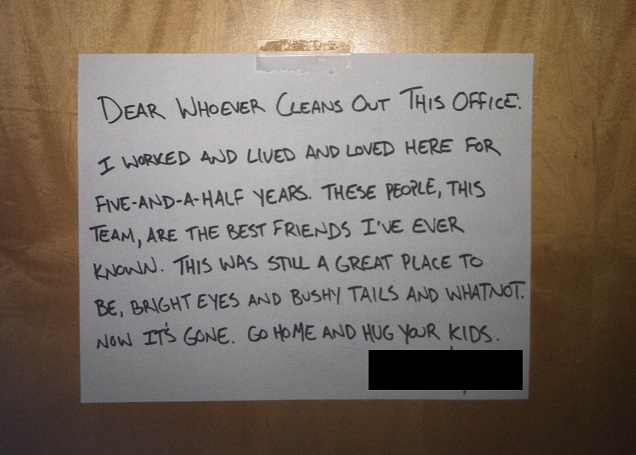

One coworker — the nicest, sweetest human I’ve ever worked with — left a note on his office door for the movers:

A month later, Game Developer magazine would name us one of their top 30 upcoming developers… with a last-minute editor’s note.

And that’s how our studio closed.

Go home and hug your kids.

Comments

9 responses to “Video Game Layoff Stories”

In all fairness this is not isolated to game development.

As someone who is halfway through a Game Design degree…

I should not have read this.

As someone who has finished one…

I agree.

As someone who finished a Games arts degree in 2008, I already knew this.

This is actually the exact kind of thing that people need to read when going through a game design course. It’s sad but it’s an incredibly unstable industry, and lay-offs and project cancellations are something that developers need to be prepared for.

Boohoo, poor devs. You want REAL game-dev layoff horror stories, read the letters sent in by game TESTERS over on The Trenches. Devs are treated like fucking royalty compared to QA.

(http://trenchescomic.com/tales)

(Edit: No really. You read the stories in the article above, your heart goes out to them, you think as a knee-jerk that calling this tame is a douche move? Go read The Trenches.)

I always felt terrible when anyone got let go where I worked, QA included. Most of these coworkers were also friends who I had worked with daily for years. On top of that, good QA is really undervalued. Just finding people with the determination and professionalism to play the same game 8+ hours a day/night a week (calendar week, not business hours week) for months/years of time is a mission in and off itself. To lose them to budget cuts (but retain “useless” devs) is just so wrong!

Working with outsourced QA where bug reports consists of no screenshots, no log outputs, no crashdumps and a one line message that says “game crashed after startup” is just so damn frustrating when you know what could have been.

It’s not really fair to talk down the problems these devs have had to deal with, but I won’t argue that Testers are the guys who get stepped on before anybody else, which is sad considering that they are the only safety net the devs have between them and the public. I’ve got a huge amount of respect for those guys and gals.

I make a point to avoid reading them, can’t handle it.