In May of 1963, thousands of black protesters — many of them school children — marched on Birmingham, Alabama to draw attention to the city’s entrenched segregation. Later that year in September, Marvel would publish the very first issue of The X-Men, a series clearly influenced by the Civil Rights Movement.

All images: Marvel Comics

Though the Civil Right Movement had been well under way before the Birmingham protests, images plucked from media coverage at the time would come to symbolise the fight for black rights. With a series of coordinated marches and sit-ins that were scheduled throughout the entire year, protesters were able to put serious economic pressure on local businesses who supported Birmingham’s segregationist policies. The Birmingham Police Department responded by throwing hundreds of the protesters into city gaols until there was no more space. When the protesters kept coming, the police met them with attack dogs and fire hoses.

Although it’s often brought up in discussions about how comic books have always been important sites of social and political discourse, The X-Men‘s Professor Xavier and Magneto are not the perfect parallels to MLK and Malcolm X that many comics fans make them out to be.

To liken Magneto to Malcolm X, for example, is to reduce the entirety of the latter’s life and politics down to a set of destructive, dramatic ideas with villainous implications. Whereas black people were (and still are) historically disenfranchised people agitating for their rights, mutants were formerly “normal” people who suddenly found themselves discriminated against because of their newfound changes. Minorities though they may have been, the original X-Men and Brotherhood of Evil Mutants were still a group of white folks who were largely able to move through the world unburdened by their technical otherness if they chose to do so.

But 1963 was a different time and there’s something to be said for the idea that Stan Lee and X-Men co-creator Jack Kirby were strongly influenced by the social movements of the time. The X-Men didn’t always provide the sharpest critiques of bigotry by modern standards, but that wasn’t exactly that Lee and Kirby were chiefly concerned with. But by the time Chris Claremont began defining the X-Men’s tone in the ’80s, Marvel had begun using them as their go-to characters for stories about oppression.

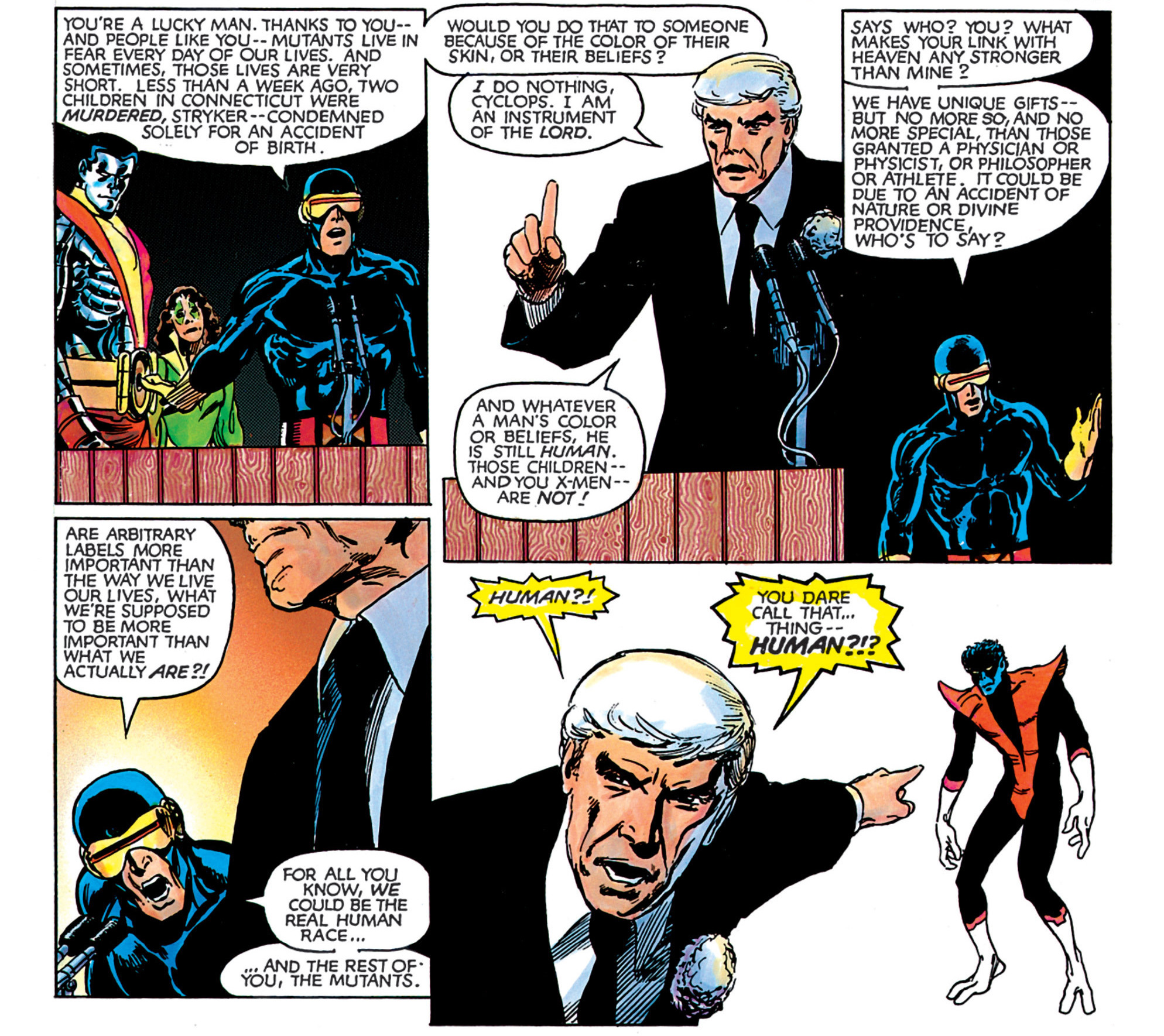

In 1981, Uncanny X-Men writer Chris Claremont acknowledged that the X-Men brand had become Marvel’s signature book about “racism, bigotry and prejudice“, concepts it explored beautifully in X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills, written by Claremont with art from Brent Anderson.

The 1982 graphic novel revolves around crazed, evangelical reverend William Stryker as he attempts to use Xavier’s telepathy to exterminate the world’s mutants. Stryker’s fear and hatred of mutants is a potent blend of religious fanaticism and shame that his own infant son was a mutant. Stryker’s story was one about mutant discrimination, yes, but it ultimately focused on the ways in which internalised hatred can corrupt and destroy a person.

Today when conversations about civil rights and the importance of speaking up against tyranny are more important than ever, the X-Men’s stories about anti-mutant hatred don’t have quite the same impact they once did.

A significant part of that has to do with how our cultural conversations about race, discrimination and inclusion have changed since the ’60s. But, if we’re really getting down to brass tacks, it’s because Marvel’s world has expanded so much that mutants aren’t really “special” any more. Why would people hate mutants in a world chock full of superfolk?

Things have been… weird with the X-Men for a while now for reasons that Marvel won’t explicitly acknowledge, but everyone assumes is because Fox owning the rights to the X-Men cinematic franchise (understandably) pisses Marvel Studios off. At a time when comic book television shows and movies are prospering, the mutants of Marvel’s books have been dealing with multiple extinction-level threats that have left some of its most iconic characters very, very dead for more than a little while. First, the Scarlet Witch depowered 90 per cent of the world’s mutant population in 2005’s House of M event and, more recently, the Terrigen Mists that gave Inhumans their powers were discovered to be toxic to mutants, threatening to wipe them all out.

Though they have been marginally involved in some of Marvel’s other larger events such as Secret Empire, persecution and being hated by baseline humans is still the mutants’ main thing. Both X-Men: Blue and X-Men: Gold‘s respective teams have had to deal with anti-mutant hatred from crowds of people that they have just saved, while joking about the sheer number of times mutants have saved humanity. You’re meant to laugh at the joke, but when you think about it, it really doesn’t make much sense that people would still have an irrational fear of mutants in a world where super heroics performed by people with strange abilities are a daily occurrence.

Marvel’s books are populated by dozens of magic users, mutates, aliens, hybrids and other genetic anomalies who naturally, spontaneously present with super abilities. People with powers may still be a minority, but they aren’t so uncommon that the public would still find the idea of mutants as fantastical and terrifying as they once did.

One could play devil’s advocate and make the argument that the actual relative “normalness” of the X-Men is the point — that people’s hatred of them (but not other superheroes) is purposefully absurd in order to illustrate how illogical racism is. But that articulation of “racism is bad” is built upon the idea that despite appearing different, everyone is actually the exact same inside “where it counts”. It looks past the self and doesn’t really take into account the notion that all people deserve mutual respect and understanding regardless of whatever differences may exist between them. People are different and we’re living in an age where more and more marginalised people are learning to see their differences as things about themselves to celebrate.

In order for the X-Men‘s message about acceptance and inclusion to ring true in 2017, the stories that Marvel uses them to tell need to become something more. As pieces of cultural commentary, the X-Men’s narratives has always been at their strongest when it zeroes in on a specific issue that different characters frame in unique ways. The Legacy Virus plotline from the early ’90s wasn’t designed to scare people about HIV/AIDS, it illustrated how a virus can move through, attack, and fundamentally change the way that a select community of minorities (such as mutants or gay men) experience the world. It was a story about how the “mutant experience” is far from universal and that one event central to mutants such as the Legacy outbreak would naturally lead to a variety of reactions.

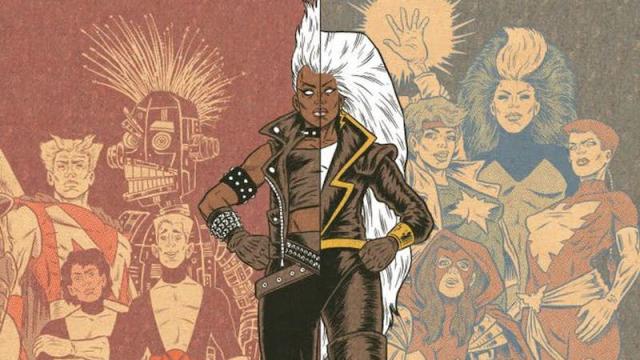

Those are the kinds of textured, nuanced stories that capitalise on the X-Men‘s core strengths as a property, and Marvel’s more than capable of telling them today. The key, though, is to put less emphasis on the “mutant as [insert minority here]” metaphor. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality is deeply rooted in the black, feminist academic from which it sprung in the late ’80s, and it’s a powerful framework for understanding how the multiple identities that we all embody influence our personal experiences with power and oppression. Storm, for example, is not just a mutant. She is a black, female, immigrant mutant whose various identities affect the kinds of power she’s able to exercise in different settings.

Storm’s depictions over the years as a thief, a punk rocker, witch and queen have afforded the character the room to grow into and inhabit many different parts of herself (sometimes simultaneously) that aren’t expressly related to her being a mutant. That is why she’s one of the most iconic comic book characters of all time, to say nothing of her status as an X-Man. That same kind of breadth of identity is what the X-Men brand needs as a whole, and the best way to go about achieving it is to ease up on the whole “nobody likes mutants” thing. We’ve spent decades seeing mutants join teams with other mutants seemingly for no other reason than the fact that they’re all mutants. The X-Men should throw its characters into wilder situations than that and force them to unpack more complicated questions.

How does a deeply religious mutant such as Nightcrawler relate to the modern papacy that’s so wildly different than the one that existed when we were first introduced to the character? What happens when a mutant with a perfectly useful but rather common superpower that’s already over-represented on superteams decides to try and become a superhero?

Rather than relying on a toothless sort of umbrella anti-mutant racism, the X-Men should be tackling those stories head on in no uncertain terms. Digging into those kinds of narratives wouldn’t detract from the fact that the X-Men are mutants, but rather would emphasise that mutants, like all people, are multidimensional beings.

Right now, the only thing that really seems to be holding Marvel’s mutants together is the fact that they’re all mutants, and while that makes a sort of historical sense, it’s holding the X-Men back from its full potential. We’ve spent years listening to mutants talk about how humanity hates them for being different. But what does it mean to be a mutant in a world full of other beings who are basically mutants in every other way except their name?

Merely existing and championing its message of social change was the first step of the X-Men‘s evolution, and the second was the broadening of its cast to include characters from all walks of life. Now, as the X-Men face a future fraught with flagging comics sales and an uneasy tension between film studios, it’s time for them to evolve once again.

Comments