David Walker is busy. He’s co-writing with co-writer Chuck Brown and artist Sanford Greene. But, despite the fact that the veteran writer has worked with one of the Big Two and the biggest outlet for creator-owned comics, Walker’s announced his gutsiest move yet: launching a self-publishing company.

A few weeks back, I spoke with Walker and Bendis about Naomi, the splashy new title that’s part of Bendis’ youth-centric Wonder Comics initiative. Shortly after that, Walker announced the debut of Solid Comix, a venture where he’s going to be self-publishing two new series close to his heart. I called Walker again to talk about this newest path, and the interview that follows is drawn from both conversations.

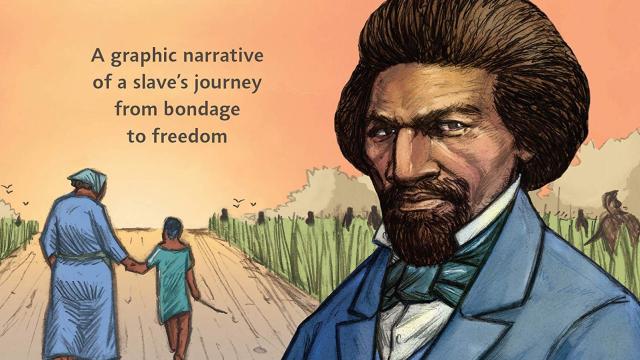

io9: Your new graphic-novel biography of Frederick Douglass has been years in the making. I wanted to start by asking if you learned anything about him that you didn’t already know, because when we’re growing up, we get an easily digestible version of black historical figures.

Walker: Oh, man. You hit the nail on the head. A lot of it is that American history, in general, just tends to be presented as easily digestible, especially when it comes to black folks. And so, in terms of Frederick Douglass, honestly, just about everything I learned during research felt fresh. I knew the most basic stuff: OK, he was a slave…and he escaped from slavery…and he was a speaker and a writer. That’s it.

When I was younger, I’d read his first autobiography, but I’d forgotten a lot of it because it had been 20, 30 years ago. So, everything was very eye-opening to me. Especially, you know, when I started getting to some of the deeper stuff, like his relationship with Abraham Lincoln, John Brown, and other key historical figures. That all really took me by surprise. I always tell people my favourite form of procrastination is research, and so, when I was researching his relationship with John Brown, I kind of went down the John Brown rabbit hole and really started understanding John Brown’s role in both abolitionism, but also the preludes to Civil War and the Missouri Compromise—all these sorts of things. And it was just endlessly fascinating to me, to the point that I’m still reading all this sort of stuff. There’s still a stack of books I’m going through to teach myself and try to learn more.

io9: What’s interesting about Bitter Root, Frederick Douglass, and the other work that you’re putting out now is that you’re dealing with the black experience in America in histories that are both real and fictional. Is there a push-and-pull, give-and-take? Does one feed the other?

Walker: Well, there’s so many stories that haven’t been told, especially when it comes to black folks and the black experience in America. Going back to Frederick Douglass, as I was doing all this research, I learned about all these other abolitionists whose names started coming up I had never heard of before. A more contemporary equivalent would be when we talk about the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘50s and ‘60s, and mostly talk about Martin Luther King, Jr. Maybe we’ll mention Rosa Parks…

io9: But nobody talks about Bayard Rustin.

Walker: Nobody talks about Bayard Rustin, at all. Or A. Phillip Randolph or even Ralph Abernathy. The names are…it’s endless. Fannie Lou Hamer. It’s that sort of thing. All these stories need to be told. And I think that if we don’t know them, if we don’t understand in our history, then we’re really doing a disservice, not only to the past, but we’re not helping ourselves into the future.

We really need to understand our history because the less you know, the more incomplete you are. Frederick Douglass talked about this. He didn’t know who his father was. He didn’t know where in Africa he came from. He was always talking about this emptiness within him, this incompleteness, and I think we all have that even if we don’t necessarily realise we have that. And it comes back to what I talk about in terms of representation and feeling a sense of belonging. Growing up as a kid, all my favourite superheroes, all my favourite comic books, the vast majority of them were white guys.

And it’s not to say there’s anything wrong with that, but, then you have to look at what the other side of the equation is. What it is that you’re getting? And if you’re a black person, or a person of colour, or a woman, what are the representations that you’re seeing? And are they all problematic if they exist at all? And I just feel like, I don’t want other young people to go through what I went through when I was young. Now I’m an old man, and I’d just like to see things change, a little bit.

io9: How do you and Chuck Brown write something fictional like Bitter Root and still have that truth be at the core of it, without having it feel like a cliche?

Walker: Sometimes I think everything is a cliché. How to not make it feel like a cliché—a lot of that is determined by your audience, you know? Because, it’s just the matter of, “Is it a first-degree cliché? Or a third-degree cliché?” You know?

But for me, a lot of it comes down to the characters and trying to get your characters to have a ring of truth and authenticity to them. With Bitter Root, it was Chuck and I sitting down and talking about this and saying, “OK, we’ve got this character, but there needs to be more to this character than what’s on the surface.” We have the character Blink, and, you know, she’s a fighter but there needs to be more than the fact that she’s just a cool fighter. And I said, “Well, it’s 1924. This wouldn’t be acceptable for her to be a fighter.” This is how society was, so, let’s have her be really good at it, but have nobody wants her to do it, you know? She’s the only one who wants to do it. And right there, that begins your mining of a little bit of truth.

Black folks too often—when we’re represented in pop culture—we’re not represented as human beings. We’re sort of ambassadors of the race. And somewhat clichéd, in that regard. So, to me, it was just important to try and give all these characters some semblance of humanity.

io9: What have you been enjoying in terms of work that you feel adds dimensionality to representations of black characters?

Walker: One of the last things that really got me excited was Ezra Clayton Daniel’s book Upgrade Soul. it’s been out for a little while now and I was really fortunate in that I read that book a couple years back, when he first finished it. And I look at that and think there’s some great black characters in there, and they’re flawed and some of them are kind of evil and some of them are kind of good, but I love that book so much. And it’s about trading in your humanity, both physically and I guess on a spiritual level—and I absolutely loved that book.

io9: The most surprising thing about your career right now is the announcement of Solid Comix, a new imprint where you’re going to be self-publishing your own work. You’re a man whose published many a comic at this point and you certainly could have set these projects up elsewhere, including Image where creators have full editorial control. You self-published Bad-Azz Mofo Magazine for many years but why do these new comics projects by yourself from soup to nuts?

Walker: Well, that’s a really good question. I think the Image model is great and obviously, I’m doing Bitter Root with Image and I hope to do more projects through Image. But not every single project makes sense to do with them. And if it doesn’t make sense to do it with Image, it almost doesn’t make sense to do with any other publisher.

When I say it doesn’t make much sense to do it with Image, it’s because it’s almost like there’s two comic book markets. Right? The direct market, the retailers, where the fans go, they order their stuff through Diamond…we all know that market. But then there’s that other market where you’re going to conventions where you have a fan base and are able to sell stuff online. You can make some money doing that sort of stuff but the thresholds aren’t as high if you’re going to a publisher like Image. You don’t have to worry about the pre-orders from Diamond.

Fighting for shelf space at the retailers is really crucial. Because there’s just not a lot of it. Even if you eliminate Marvel and DC from the equation, you’re still competing with a ton of publishers and a ton of titles. Image or Boom or Dynamite or Dark Horse, Action Lab, Vault, Lion Forge, so many of them! They’re all fighting for that same real estate. If you don’t have good sales for whatever reason—more than a thousand units—most publishers are going to look at that book as a bomb. The reality is there’s publishers who can’t even move a thousand units a title.

I’ve been doing conventions for years and selling my own books at them. Why not just sell the books where they’re selling anyway? It’s not so much about eliminating the middleman; it’s recognising that you’re in the financial hold of whatever publisher you’re working with. When a book doesn’t sell, it isn’t necessarily through any fault of yours or their’s. It just makes more sense with certain key projects to just put them out myself.

io9: I watched the videos that you did around the announcement and one of the things that was interesting to me is you’re seeing your Solid Comix work as an intimate, hand-sold product. Not quite a collector’s item, but something that is the most personal way you can deliver stories to readers. Do I have that right?

Walker: Yes, you do. actually. It’s kind of interesting because it’s like…“Wow, I guess I did say it that way.”

You put your heart and soul into a comic. It doesn’t matter if it something you own or if it’s work-for-hire, but you put all this energy into it. To see it not sell well—for a whole host of reasons that don’t necessarily have anything to do with quality—is hard.

It has to do, again, with that valuable real estate space on the shelves at every retailer in the country. And it has to deal with, you know, how much it costs to advertise in Diamond. It has to do with how much people would just rather go into the stores on Wednesday and buy X-Men, or Batman, versus your little indie title. And it’s kind of heartbreaking. You put all this time and energy into a book, and it doesn’t necessarily sell. And it’s not a reflection of you or a total reflection of the industry; it’s just a reflection of all these weird factors that coalesce.

But you can take that same book and go to a convention, whether it’s a bigger convention like Emerald City or Wonder Con, or a small event like Black Comics Fest. You can meet people, talk to them, engage with them, and you can sell your wares, you know? And there’s part of me that really likes that. I miss doing that from the old days. Maybe I’ll get back into it and be like, “I’m too old for this”…

These projects that I’m doing through Solid, it’s not like they were rejected by any publishers. In fact, without saying which project or character or publisher, two of the four books in development right now were offered publishing deals. But I looked at some of the specifics of the publishing deals and what was going on with the IP rights and the threshold of units that would have to be sold before revenue was being generated by me and my team, and I was just like… “Yeah, this doesn’t make sense.” I’m not seeing that certain publishers are able to move those sort of units.

That’s another reality of the industry: Even if it’s creator-owned, right, you have to move a certain number of units just to break even on the cost of production. Then you have to move a certain amount of units before you go into any sort of profit royalty of anything like that. And then on top of that, if you want to sell your product at a convention, or even through your website, you’ve got to buy that from the publisher. And sometimes that’s just not the most cost effective way to do things.

There comes a time where it’s like, “OK, well, wait a sec. Does it make sense to do this book through one of them when I can do it on my own?” Go to Kickstarter, borrow some money from a couple of key friends and do a print run that’s going to meet the needs as I project them…and again, I may discover this isn’t nearly as fun as it was 25 years ago. But I had to give it a shot.

io9: I have friends who own independent bookstores and they’ve always talked about the importance of hand-selling certain books. You have to have the person who knows the books and the same person who knows the customer. There’s a tragedy when a book can’t find its reader. There could be somebody out there for whom One Fall is just perfect for, but, you know, if you went to the direct market and didn’t find anybody, it’d be a damn shame.

Walker: There’s part of me that’s like, “Man, you done lost your mind.” I was thinking that today because we’re prepping the first Kickstarter and I got two friends helping me with it. But it’s like, “This is all on you, man.” And there was a moment this afternoon where I was like, “What am I doing?” And I got over it. Let’s just move forward and do this thing.

io9: You mentioned Kickstarter. How are you approaching crowdfunding? You have people like Spike Troutman who runs Iron Circus, and she’s done amazing work with crowdfunding. Are you learning from what she’s done? What happens if you don’t meet the funding goals?

Walker: These are all good questions. So, I like to tell people that I was the one who discovered Spike. I’ve known Spike for pushing up on 20 years. Amazing talent. I met her either at APE or San Diego, probably in the late ‘90s, early 2000s, and I tried to hire her. Didn’t have a very big budget. And I was like, “I want to hire you,” and she’s like, “OK, here’s my rate.” And I was like, “Oh! I can’t afford you.” And she’s like, “Well, I’m not lowering my rate.” I knew in that moment that, someday, I’ll probably go to her for a job. She’s got an incredible business sense. So yeah, it’s funny because I haven’t talked to her in about a year, but, every time I see her at a convention, I picked her brain about Kickstarter. Cal McDonald was another person I talked to. Tameeka Stotts. Greg Rucka. Greg Pak. So, I had been looking at what other people do. And none of that prepares you, you know? I realise there’s a certain amount of flying by the seat of my pants.

And I also realise, if it fails, if we don’t reach our goal, we just do it again. And I rethink the strategy. I budget for a lower print run. And here’s the thing, too—this is really crucial—I have money and I am putting money into this. I’m obviously not putting money into the Kickstarter because you can’t do that. I just sent [artist] Sean [Damien Hill] money today to cover the art he’s doing on The Hated. There is sort of a backup plan, but I’m not going to do the all-or-nothing. I’m not going to put my money into this just because it’s not feasible. And if it doesn’t work out, the reality is I’ll do something. Because that’s sort of how I am. This didn’t work? OK. I’m going to sit here in the corner and cry for a couple days. And then I’m going to move on. But again, it’s not that I couldn’t find a publisher to handle any of these projects that I’m doing—because I could. I’m questioning the mainstream market as it exists, and the place it leaves for indie folks. I’m working for DC and I’ve worked for Marvel and the mainstream—but that’s not my only goal.

io9: It just struck me how it is very reminiscent of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Melvin Van Peebles went outside of studios and he bootstrapped something that no studio would greenlight or finance back in the day. And that started a whole new niche of cinema. That probably speaks to your proclivities in more ways than one.

Walker: Yeah. And even with comics, you look at Brother Man. I’ve known Dawud and Guy since Brother Man was originally coming out and they were doing comic strips in Rap Pages Magazine. I’m a huge fan of their work and truly inspired by them. And they’re still doing that.

I went into the comic shop yesterday. It was Wednesday. And there’s some great stuff that I bought, but also a lot of stuff I knew wasn’t on the shelves. Again, not the fault of a publisher, per se—or a retailer, or the distribution person. Just, this isn’t working out. And if a title doesn’t sell well by the first or second issue, retailers are ordering less. It amazes me how many fans still don’t understand the concept of the pre-order. But I can’t say that in a disparaging way, because there are times I’m guilty of that, too. I’ll walk into a store and be like, “Oh. This is out? I meant to pre-order this.” But I didn’t. Thankfully, it’s here.

io9: Same thing happens in video games. The push to preorder puts the onus on the consumer. If comics were different, we wouldn’t all have to be flogging people to pre-order a book. We could allow them to make their own decision in the release window, but things don’t work like that anymore. What’s interesting about what you’re doing with Solid is that it’s an experiment in narrow-casting and right-sizing. You’re trying to find “what’s the exact amount of these I can print to reach out to people who want to read it, be profitable, and make it self-sustaining?” And what does a David Walker fan want to read? Are these concepts where you thought, “I can sell a cowboy comic with a black female lead to this specific audience because they don’t have that and I can give it to them.”

Walker: I’d like to say I thought that clearly! [laughs] There is a certain amount of that. I was at the Keystone Comic-Con in Philly last year and there was a strong pro wrestling presence. And I realised there’s some wrestling podcasts I listen to and people I follow on social media and I was like, “There’s a lot of pro-wrestling fans who are comic book fans.” Boom is doing their WWE comic and that’s a solid book. There’s an indie book out there called Headlock.

And I’m like, “These are all great books, but not what Brett and I are doing on One Fall…” We’ve got something in mind we want to do. With The Hated, that’s the ultimate labour of love, more than any of the other projects I’m doing. Sean was the right artist at the right time; it took me a long time to find somebody I thought would do justice to this book. And with that, I was like, “Well, if this is going to fail? Let it fail because I did it all wrong,” as opposed to finding someone who wants to publish it but doesn’t find its groove there and all the books are sitting in a warehouse.

io9: Can you talk in broad strokes about what you’re trying to do with Solid and what you did with BAMF? What’s changed in terms of the business of self-publishing that’s made it easier or harder for you?

Walker: I want to try to print domestically and if I can, I want to do it as close to home as humanly possible. Because part of being a small business person is trying to support other businesses around you, if you can. Doesn’t always make sense to do that but sometimes it does.

In the old days—the ‘90s into the early 2000s—if you wanted to print something, you had to go to an offset printer and you had to do a minimum print run of a thousand. Minimum. And then you had to pay for the shipping. You might not know for sure if you were going to move a thousand. But you had to have a thousand. Now the good thing was, back in those days, when I was doing Bad-Azz Mofo, that was a magazine with a little bit of comics and comic related stuff in it. You had Tower Records, Tower Books, and Borders. Virgin Megastores was still around and there was a ton of magazine shops and newspaper stands. So there was a whole market that’s sadly gone away. But at the same time, you don’t have to do that minimum print run of a thousand now.

A lot of places have really good laser printers and the print-on-demand thing has made it possible to do shorter print runs. In some cases, you can get a full-colour magazine or comic now for maybe two dollars a unit—maybe more—which is far less than what a full-colour offset would have cost you 15, 20 years ago. So all that has changed.

I’ve been following Kickstarter for years now, and part of me was like, “Oh, do I really want to do this? I don’t know, it seems like such hard work.” But the more time I spent in comics—because I never thought too seriously about self-publishing—I thought about maybe bringing Bad-Azz Mofo back in some capacity. But the more time I spent in comics, the more time I was doing in conventions and looking at certain titles I had written not perform well…and just go, “OK, well—I love this medium and I want to do some stuff but I’m going to have to play by that secondary set of rules.” If you want to be a musician or play basketball, you can play basketball. Go down to the local park or playground or gym and get a game of pick up any time. You want to be a musician, you can get an instrument and play and go to an open mic. You don’t have to be in a big band that’s touring all over the world or make it on a pro ball team to do the things that you love. And that’s…at the end of the day, that’s kind of what I realised. I love comics, but, what part of comics do I love? And you know, it’s great to work for Marvel, DC—it’s not the be-all, end-all for me.

io9: Let’s talk about the books themselves, One Fall and The Hated.

Walker: One Fall is a book I’m doing with Brett Weldele, who’s an old friend of mine. We’ve been saying this we should do a book together over 15 years. This last time, Brett said, “I want to do a wrestling comic, but I don’t want it to be like other wrestling comics. I want to lean into the true, over-the-top nature of the backstory of wrestling.”

I was like, “Ooh!” Suddenly that becomes fascinating to me, right? And then I said, “Well, when you talk about the backstory, are you talking—how ridiculous or over the top or absurd do you want to get?” So, as an example, I said the Undertaker supposedly has come back from the dead before but we all know that he really hasn’t. “No, that’s what I want to lean into.” OK, so, right there I said, ‘How about if our lead character is a guy who, in some capacity we haven’t figured out yet, keeps coming back from the dead?” And Brett was like, “OK, let’s do it.”

We’re both really big fans of kung fu movies and samurai movies and grindhouse films so we started talking about movies like Master of the Flying Guillotine. And then we started talking about Italian exploitation movies like 1990: The Bronx Warriors, and Warlords of the Wasteland. Enzo Castellari and directors like that. And we’re like,“Yeah, let’s just throw all those elements into a pot and see what happens.” And the key was we didn’t throw it into a very big pot, so, if it didn’t taste good we didn’t waste all our ingredients. And so we started to put together a story, and the story of One Fall is basically set in a world where professional wrestling is the world’s favourite pastime. It is the most popular sport in the world and it’s not the pre-scripted thing we think of as professional wrestling. The way wrestling treats itself as being real is how real it is in this world.

io9: It’s 100 per cent kayfabe 24/7.

Walker: Exactly. To the extent where the President of the United States is an ex-professional wrestler. And all of the soft drinks are wrestling-themed. It’s taking some of the more obscure things from our world— you know, like, we’ve actually had elected officials who were pro wrestlers. And then throwing the supernatural into the mix. Our lead character is Jimmy King, a guy named the Resurrector. He’s a third generation wrestler, the latest person in his family to inherit the family curse: every time he dies, he comes back to life. It was his dad’s gimmick, it was his grandfather’s gimmick. And at some point, he knows he’ll die and it will be for real. It’ll last and he won’t come back from the grave.

Then the curse is passed on to one of his children. And so a lot of it is about him grappling with—no pun intended—his family curse, but also dealing with, “Can I be more in my life? Can I do more with my life? How can I make something better for my children?” That sort of stuff. And then we introduce a ridiculous cast of characters around him.

io9: And The Hated seems like it’s on the complete opposite end of the spectrum, tonally.

Walker: Yes. The Hated is just a straight western. No supernatural element to it. It’s loosely based on a screenplay I wrote about 25 years ago, maybe 30 years ago. It takes place after the Civil War, and the main character is Araminta Free, a woman who was a runaway slave and a conductor on the underground railroad. She’s been a spy for the Union army, too, so, she’s essentially Harriet Tubman meets Foxy Brown. (That is actually Harriet Tubman’s birth name. Araminta.) The series takes places after the Civil War, when she’s become a bounty hunter. She specialises in is two things: one is bringing Confederate war criminals to justice; the other is tracking down lost family members of ex-slaves and reuniting those families. And so this story is what I’m hoping to be the first of multiple graphic novels, about her going up against some ex-Confederate war criminals as she looks for her children who were sold away when she was younger, before she escaped. And then getting caught in very traditional good guys versus bad guys Western conflict.

I’m looking at it as a reclamation of the Western. I don’t want to compare it to Django Unchained for a whole host of reasons, but the Western was this mythological folklore we’ve all been weaned on in some capacity, but it’s left a lot out. It’s left women out, it’s left black folks out, and I was like, “Alright.” And everyone will tell you, Westerns don’t sell. That’s because they’re always the same old Western.

I was 21 when I wrote it originally and I wanted to see a Western with nothing but black cowboys, gunslingers, and outlaws. Now that I’m 50 what I really want to see is a badass woman who is a bounty hunter who can throw down with any man. And again, she’s a cross between Harriet Tubman and Stagecoach Mary, who was a real person. And then Foxy Brown.

Sean and I had been developing it for a while, even doing concept art. There was one publisher in particular who really wanted it. And I was just like, “You know, this deal’s not that good.” If I sign with you, and you publish this book and it doesn’t go well, for all the reasons we’ve discussed earlier—from sales to retailers not getting it—I’m going to be really pissed. I know I can move this book, because I love this thing and I know people who will love it. And they’re going to tell their friends, and they’re going to tell their friends, and it might be a slow burn, you know? That’s the other thing, too. I wrote this book for Marvel called Nighthawk.

io9: I am well aware of it, David

Walker: I know you’re well aware. But Nighthawk was a bomb in terms of sales.

io9: You bled for that book, though.

Walker: I did. And the thing is, now it has this life of its own, this cult following. But it also has a limited lifespan because the chances of Marvel keeping that in print are slim to none. The only way that book will ever stay in print once they run through the initial however-many-they-printed-up, is if that character got a TV show or some deal. I can’t fault Marvel for doing that. These bigger publishers, they’re not set up for anything to have a slow burn and to find a life of its own. And that, as a creator, that’s heartbreaking. It’s heartbreaking for a work-for-hire job you did, it feels ten thousand times worse when it’s a creator-owned book. When you’re spending 10 bucks a unit to buy these books from this publisher to then haul them across country and sell them at conventions, you might as well just do it yourself.

Comments