Minutes after I walked through a metal detector — and some time before she was flocked by well-wishers at the best-attended gaming lecture I’ve ever been to at New York University — I recently listened to the media critic Anita Sarkeesian describe eight things she’d like to see changed in video games.

To be specific, she was describing “eight things developers can do to make games less shitty for women.”

The list was a surprise — not really for its content but for its explicit charge for change.

For the last three years, Anita Sarkeesian has been talking about how women are treated in games and has slammed the widespread sexism she sees in the portrayal of female game characters. She’s done this through a series of online videos for her non-profit, Feminist Frequency, and in lectures at conferences and even at some game studios. Her supporters cheer the idea that her influence may transform the medium; her critics fear that. They both infer a lot from her analysis of games, but at her NYU talk she left no ambiguity. She spelled out what she wants to see done, what she thinks game developers should think about doing differently.

Her list was brand new. “You get to be my guinea pigs,” she said as she took to the podium in front of a couple hundred developers, game design students and gamers, “to see how this all works.”

Near the start of her talk, she apologised for being sick and said it was the first time she’d been ill in two years. She fought back a bad cough throughout an hour-long presentation but frequently elicited applause or laughter as she spoke. This was a friendly and game-savvy crowd.

I had attended Sarkeesian’s NYU talk because I wanted to hear her outside of the pre-recorded Tropes Vs. Women In Video Games that she’s been making for the last couple of years.

I’d met her in person briefly last spring, before she won an Ambassador Award at the Game Developers Conference for her work critiquing video games. We’d e-mailed several times when I was reporting stories.

I’d seen most of her Tropes gaming videos, of course, and, frankly, not had much issue with them. Much of what she showed in them — the propensity for games to depict a disappointingly narrow range of female characters, of often using women in games as props to motivate players, of regularly sexualizing female characters to a comical degree — had rung true to me. Her material had rung true to me even as I’d recognised the complications of calling for diversity in creative work and even as I’d noticed that, sure, if you look closely enough, you can find an admirable female character even in a game that is frequently described as being insulting to women.

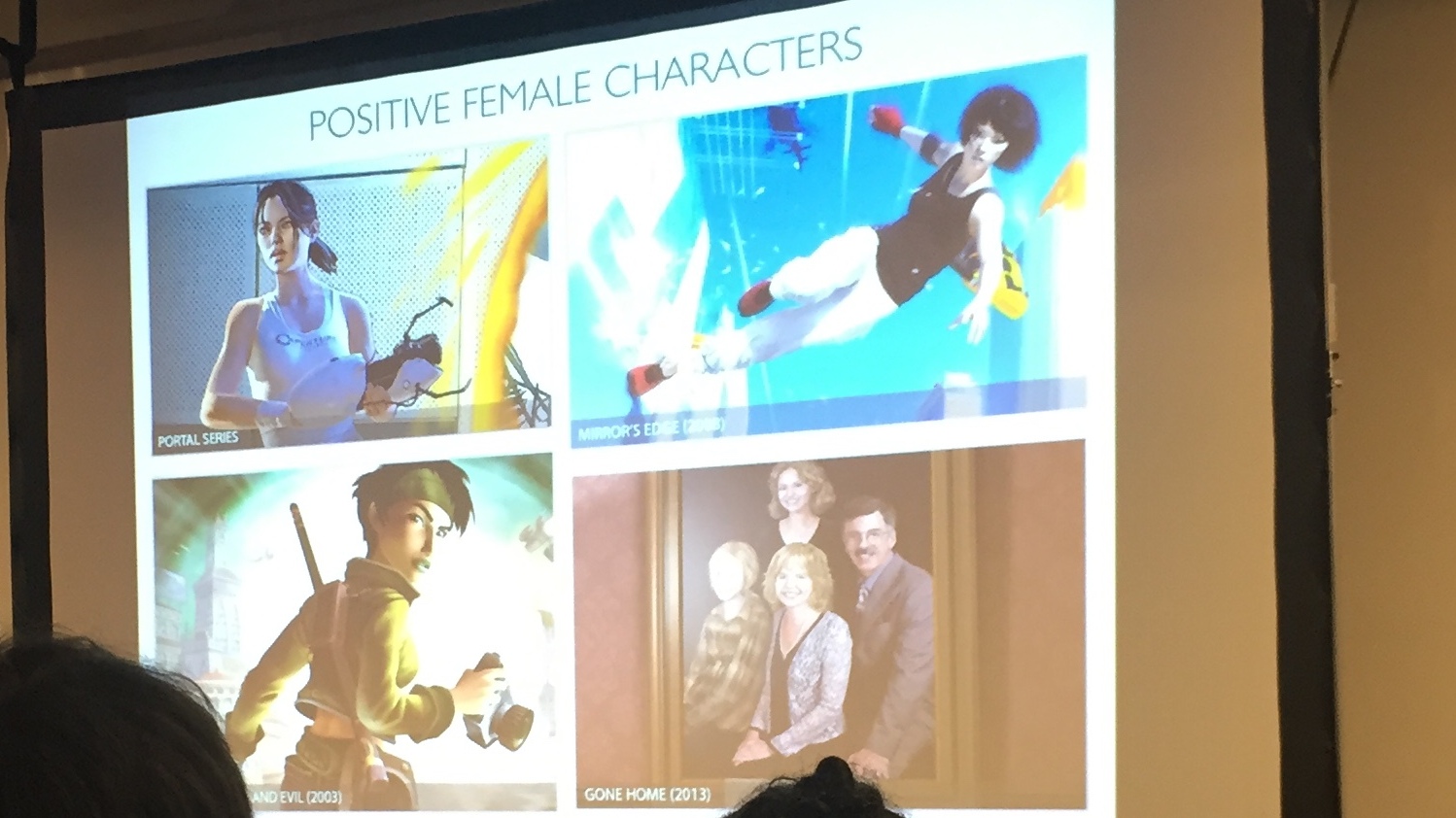

Sarkeesian is an advocate. She talks about issues that she feels have been entrenched in games but go under-discussed. Throughout her NYU talk I was struck by both her negativity and her positivity. During an unscripted Q&A, she said that modern gaming’s depiction of women was really bad. “It’s very much like one step forward, two steps back,” she said. “There are small things that come up that, you’re like, ‘That’s awesome.’ And then five other things that come up that’s like, ‘Are we still doing this?’” Throughout her description of the eight changes she’d like to see, she repeatedly mentioned games that she thought were handling things badly, but she also routinely highlighted games that she thought were doing things well.

She also kept talking, surprisingly, about how easy change in gaming could be.

- “Fixing this is, of course, incredibly easy,” she said when talking about games that may have several playable protagonists but offer few, if any, who are women.

- “Happily, this is another easy one to solve,” she said, when lamenting the sexualised grunting that she often hears from female game characters who are supposedly engaged in combat.

- A variation, when talking about how male and female characters animate very differently in some of the big-budget games she’s been playing: “The solution is obvious: just animate your women moving and sitting the way real women might move.”

The metal detectors, and the overall heightened security presence at Sarkeesian’s talk, were impossible not to notice. I heard a few attendees mutter about this being necessary or finding it absurd that a talk about women in gaming, of all things, required this kind of presence. An NYU rep told me they hadn’t set up metal detectors for any Game Center talks before. The people who make Dragon Age didn’t get this kind of security.

The added protection, I was told, was “the result of NYU Public Safety’s extensive security audit of the situation,” though NYU did not specify, despite my asking, if they were there in response to any specific threats. I’d previously reported about a bomb threat against Sarkeesian’s GDC acceptance speech nearly a year prior. An NYU security guard stood in front of the audience, watchful, as she spoke.

Sarkeesian never acknowledged the security, and she only briefly mentioned the online harassment she’s received for her work. She fielded one audience question from a guy who said a female Gamergate supporter had been at the talk, had shaken her head at much of what Sarkeesian had said, had left early and, this questioner wanted to know, what Sarkeesian would say to this woman.

“I’m happy if she cared at all and wanted to come,” Sarkeesian said, “but I seriously doubt people from Gamergate’s intentions of coming to an event where I am speaking…I think if anyone in this audience is here for Gamergate they are not here because they genuinely care and want to learn. They are coming here to be, like, ‘oh my god, that woman, that horrible evil woman that’s ruining video games.’”

She said she’d written Gamergate off, that there was no convincing them. She wanted to reach “fence-sitters,” people “who are like, ‘I’m interested, and I don’t know if I agree with you, and I’m curious.’”

As little as Sarkeesian mentioned her critics, I sensed that a lot of the start of her talk was designed to address their criticisms. First, she seemed to be challenging claims that she thinks games make people do things. “When I say that media matters and has an influence on our lives, I’m not saying it’s a 1:1 correlation or a monkey-see, monkey-do situation,” she said, “but rather that media’s influence is subtle and helps to shape our attitudes, beliefs and values for better and for worse. Media can inspire greatness and challenge the status quo or sadly, more often, it can demoralise and reinforce systems of power and privilege and oppression.”

And, second, it seemed to me she was being careful to clarify whether she loves games. In a vacuum, this might seem strange, but the idea that Sarkeesian doesn’t care much about games has been part of the narrative against her. There’s a pre-Tropes vs. Women in Video Games clip, after all, of her introducing a video about gaming by telling a college class in 2011 that “I’m not a fan of video games. I actually had to learn a lot about video games in the process of making this.”

At her talk, she showed a photo of herself as a kid, playing the Super Nintendo with a childhood friend. She recounted her efforts to get her parents to buy her a Game Boy. She talked about getting nostalgic while in college and buying a Super Nintendo to play Super Mario World.

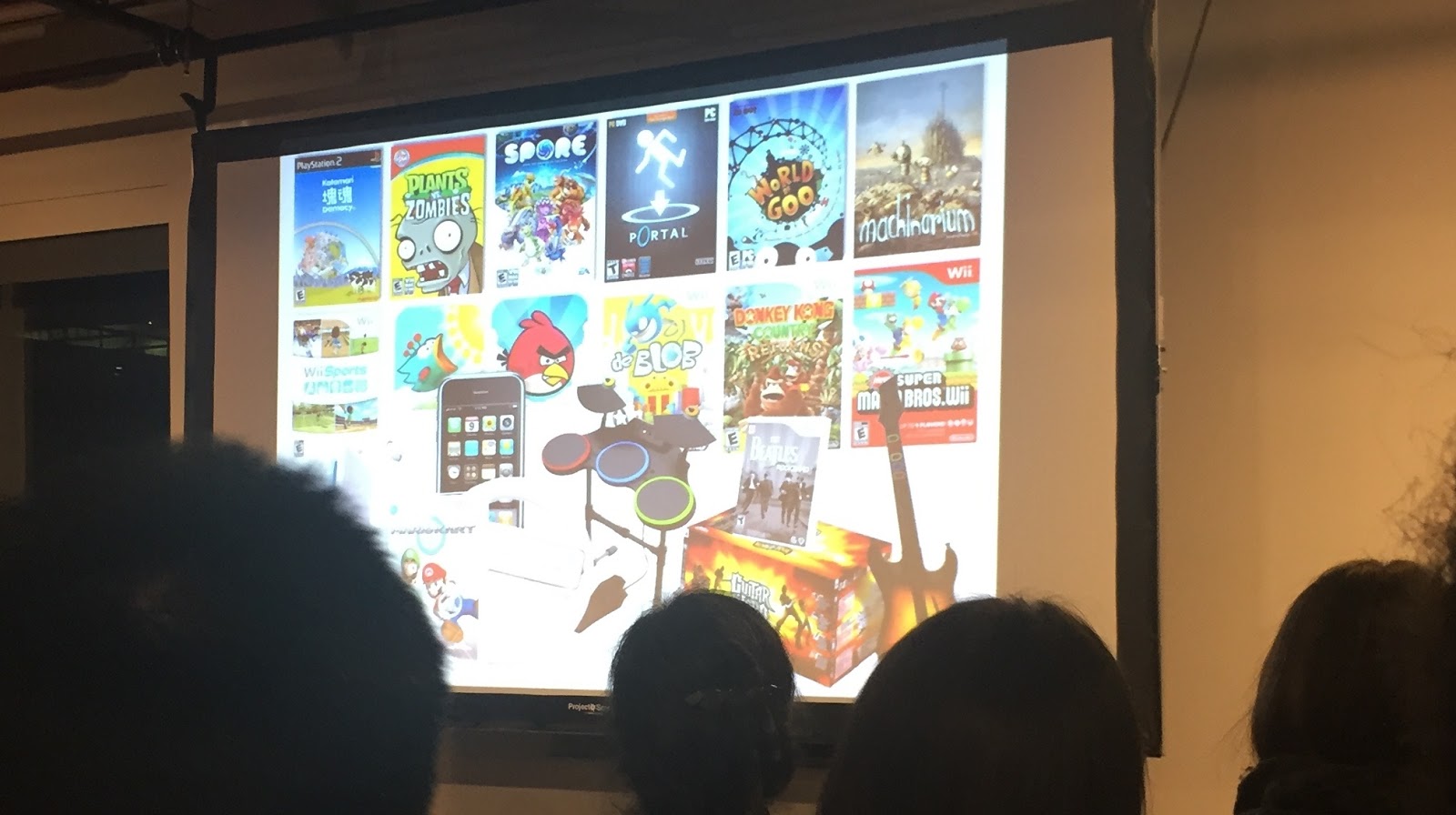

She described her relationship with gaming as “complicated,” credited the Wii for getting her back into gaming and showed a slide of Mario Kart Wii, World of Goo, Guitar Hero and Angry Birds. She said that she knew that some people didn’t consider those “real” games but that she counted them as some of her favourites.

Sarkeesian mentioned her time in grad school, which I believe was the same time she was saying in that clip that she wasn’t a fan of games. “If you asked me at the time, I would probably have said I wasn’t a gamer,” she said. Under her breath she added: “I don’t even know if I want to say that now, but whatever.”

She said she’d “bought into the bogus myth that, in order to be a real gamer, you had to be playing GTA or Call of Duty or God of War or other testosterone-infused macho posturing games which often had a sexist, toxic culture that surrounded them. So even though I was playing a lot of games — these kinds of games — I still refused to call myself a gamer, which I don’t think is uncommon.”

She would later emphasise the idea that “you can love something and be critical of it.” That, she said, “is so important to what I do and is really important to engaging with any kind of pop culture.”

“So, you’ve heard of The Wonderful 101?” Sarkeesian asked her audience, as she finally got into the Eight Things Developers Can Do To Make Games Less Shitty For Women.

“It was released in 2013 for the Wii U. There are seven main heroes. They are all colour-coded. Can you guess what colour the woman is?”

Several people in the audience shouted the predictable answer: “Pink!”

“Yeah,” she replied, and rolled the character intro for Wonder-Pink.

That’s how she set up her first request to game developers: “Avoid the Smurfette principle,” a reference to both having just one female character in an ensemble cast and the character limitations that can spring from that. There are actually some other female characters among the 101 heroes of the Wonderful 101, but of the playable ones, only one is a woman. Wonder-Pink wears pink. In her intro video she’s worried about her makeup. “Because she’s the Smurfette, her personality is: girl,” Sarkeesian said.

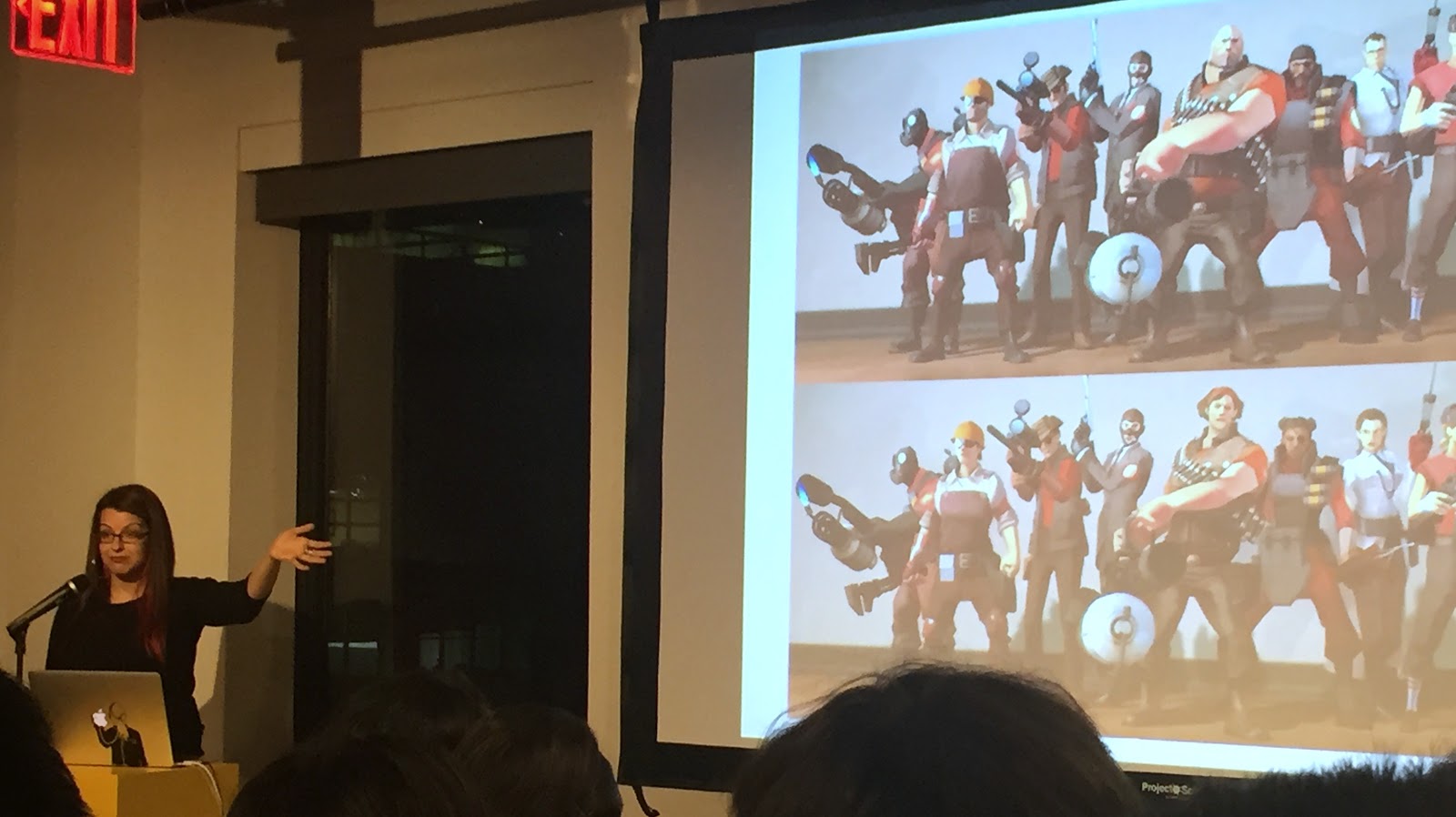

She showed a slide of Left 4 Dead 2. Four playable protagonists, one of them female. She complimented the latest Borderlands for upping the number of playable women heroes in each of the original base games from one to two (more if you count the DLC). She showed Team Fortress 2. Nine playable classes, none of them women.

“Fixing this is of course incredibly easy,” Sarkeesian said. “Just give players more diverse options. Giving players more playable female characters is the first step toward female characters, like their male counterparts, being defined more by who they are rather than simply by their gender.”

What Sarkeesian was talking about sounded like a quota, because, well, it is. “At least half of the options should be women and, really, it would be great if it was more than half the options were women, and I know some people think I’m completely loony when I say that.”

I noted her words, about what “should be” and what “would be great” and it got me thinking again about the enthusiasm and anxiety people have about her influence. It’s a tricky argument, right? Would it be bad to have more playable female characters? Would it be bad for a given game not to?

Gamers are obviously debating this. And in my experience, confident creators could deal with this kind of critique, could take from it what they found productive and stand up for their authorial independence about what didn’t mesh.

I don’t think there’s an easy answer, and it doesn’t seem to me like there’s a rule that would work across the board.

As Sarkeesian pointed to fan-art that imagined Team Fortress 2‘s cast as being all women I thought about her position as an advocate. She’d push. Developers, publishers and gamers could hear and decide for themselves what’s best to do.

Sarkeesian’s list of eight things included several straightforward requests. She called for more body diversity in female characters, lamenting the “Victoria’s Secret catalogue” physiques of so many playable women and yearning for the kind of bodies that the male characters in the upcoming Blizzard game Overwatch have.

“The blue one looks cool,” she said of the women. “The other four are similar, long legged, slender, mostly sexualised armour, high heels, lack of pants.” She contrasted that to the men. “The male characters get to be short and stocky or heft gorillas or equipped with a massive power suit. You just don’t see anything approaching this variety of body types in weights and sizes with female characters.”

She pushed for more representation of women of colour in games, and more that are neither reducing such women to ethnic stereotypes nor so divorced from their cultural history that it “is eased or invisible.” She praised Never Alone, a game featuring a female character from an Alaskan tribe. “It should not be too much to ask for for representations of people of colour whose cultural backgrounds are acknowledged and woven into their character in ways that are honest and validating.”

After playing what she said was an audio clip of a female League of Legends champion in combat (above) she called for less sexualised female-character voice-acting/grunting — “start with trying to make pain actually sound painful instead of orgasmic”. And she rejected clothing female characters in cleavage-emphasising armour whose “only functionality is to titillate young straight male player base.” For the latter, she said the amount of skin shown wasn’t the issue and recommended that game designers look to the outfits of real female soldiers and athletes for inspiration. Sarkeesian recommended that designers of fantasy and sci-fi games put female characters in similar armour and uniforms as their male counterparts and praised Dark Souls, Natural Selection 2 and XCOM for having more practical outfits.

Occasionally, as she went through these suggestions, Sarkeesian would mention counter-arguments. For example, she said that impractically-sexualised costumes communicate that a female character’s “value and worth is tied to ability to arouse straight young men.” But she added that some of her critics say that male characters are sexualised, too. She doesn’t buy it, pointing out that it’s common to, say, see female characters’ breasts jiggle and rare to see male characters’ penises do the same.

Moreover, it’s worth bearing in mind the obvious, that she’s a feminist and that her view is that men and women are perceived very differently in society. “Equal opportunity sexual objectification is not the answer here,” she said. “It actually isn’t equal.” Her view of how women are seen in much of society and culture is fundamental to her arguments: “Women are thought of and represented as sexual objects to be used by and for the sexual pleasure of others in society, and men are not viewed that way. There’s no long-standing oppressive construct of men being seen as sexual objects and reduced to that in real life.”

If you agree with her worldview, you’re likely with her on many or all of these eight things. If not, well, you’re unlikely to see much here you can back.

Going through her list, she called for game developers of third-person games to “de-emphasise the rear end of female characters,” which she said after contrasting how Catwoman’s butt sways in the third-person Batman game Arkham City with how male characters like God of War‘s Kratos have their butts covered by loincloths or trenchcoats. By contrast, she praised the presentation of the female character in the new third-person game Life Is Strange. It seemed like a subset to another argument about female character animation.

“Motion capture and animations for female characters often have them looking like they’re walking down a runway at a fashion show,” she said. “It’s as if the person directing the mo-cap session told the model to walk in the most seductive or sexy way possible rather than just asking her to walk the way a soldier or intergalactic bounty hunter or any ordinary woman going about her business might walk.”

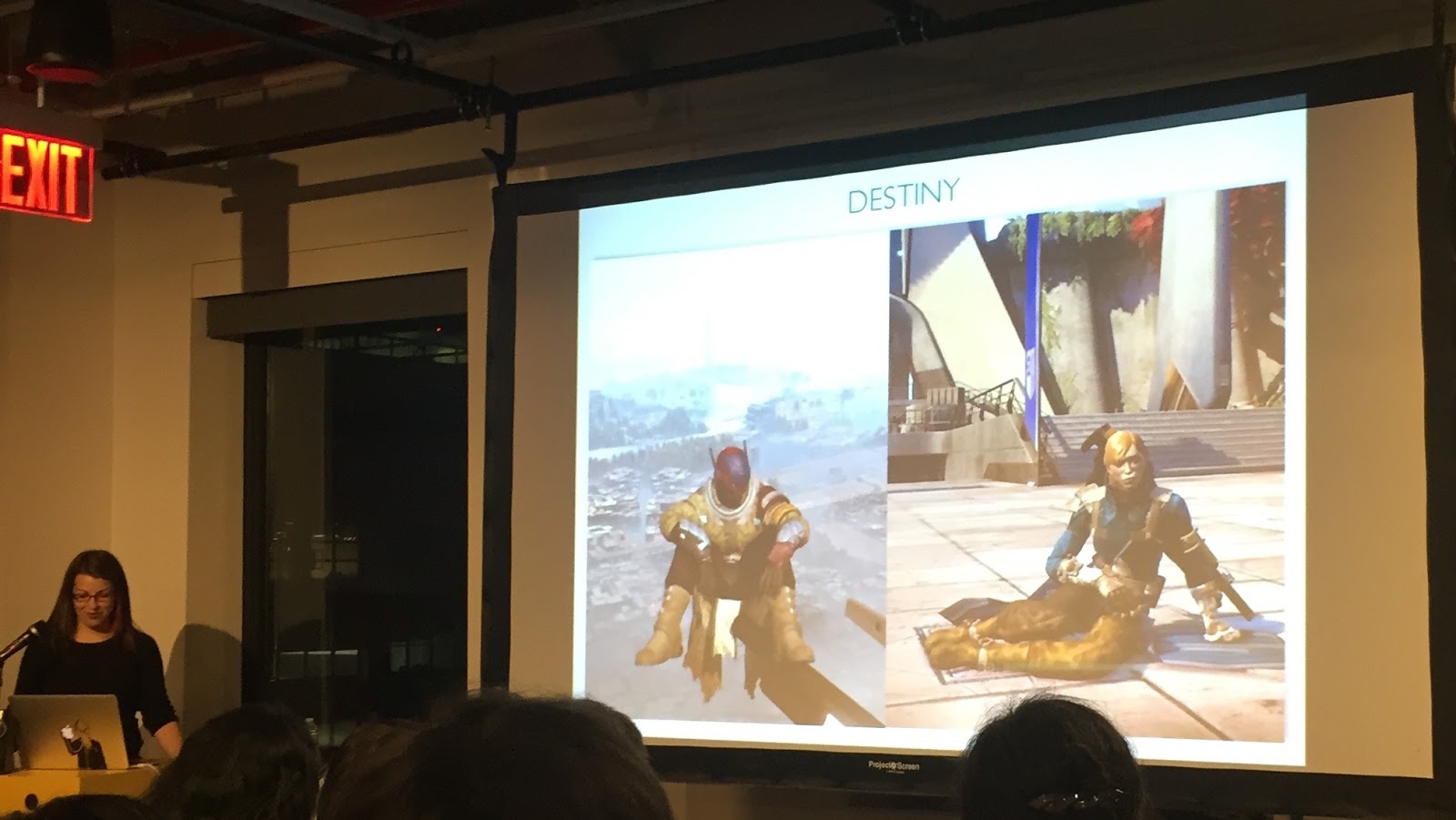

Even sitting could be a gender issue, she showed. She ran clips of how male and female characters sit in Destiny, a game that imbues its heroes of either gender with the same capabilities. When the guy sits, he just sits, feet and butt on the ground, knees up. When the female character sits, she lays on the side of her legs. “This is supposed to be a hardened space warrior and yet she is still sitting around like she’s Ariel from The Little Mermaid,” Sarkeesian said. “I mean, what the hell?”

The animation arguments were interesting but also demonstrated Sarkeesian’s emphasis on the critique of what players see, more than what they do. She has certainly been critical of the interactivity that leads players to rescuing damsels in distress, but if, say, developers changed many of the Eight Things she requested in her talk, it wouldn’t make games play differently, if at all. That might explain why her criticisms of gaming occupy a different spot than other people’s criticisms about, say, free-to-play game design, game length, or downloadable content. Those latter arguments clearly and directly pertain to whether a game would be more or less fun or engaging for any player, which for many gamers is the paramount gaming concern.

Arguments about the depiction of women, however, will find a sympathetic ear among those who, like Sarkeesian, believe that less sexualized and more diverse presentations of women will make games more approachable — more fun — for more people. They won’t move people who might linger on the likely fact that changing how characters sit in Destiny or walk in Arkham City probably won’t make those games play any better.

Sarkeesian talked about how a more expansive range of female characters can open games up to new stories and experiences, but she doesn’t flat-out say that it’d make an ok game more fun. That’s not really her point. So it’s easy to see how two people might sit through the same Sarkeesian presentation and think “This completely matters” and “This doesn’t matter at all.”

Talk of gameplay brought Sarkeesian to her final point. She said she’d spoken with “well-meaning” game developers about how to handle female enemies. Many games use violence as their main means of interaction, she noted, and some developers were uneasy about if or how to put female enemies in harm’s way.

“Simply putting women in the line of fire is not in and of itself a problem,” she said. “Everything depends on framing, right? So, with that in mind here are two things to keep in mind when designing female characters. One: avoid violence in which women are framed as weak or helpless. When we critique violence against women, we’re often talking about violence in which women are being attacked or victimised specifically because they are women, which then reinforces or perpetuates a perception that women as victims and men as noble, brooding heroes…

“Two, avoid violence against female characters in which there is a sexualised element.”

She praised BioShock Infinite‘s presentation of a Columbia police force whose male and female cops wear similar uniforms. “The ideal here,” she said, “is to design combatants who just happen to be women.”

Of all of Sarkeesian’s requests, I could see this being viewed as the most well-intentioned but creatively stifling one — Why not sometimes have a sexy female enemy? Why not sometimes let a character of any type be helpless or play up their gender? — and yet it also seemed to be the one where she was trying hardest to find ways through it and where she felt like there were the worst potential negative impacts.

“Don’t make the enemies or villains sexualised,” she said, “because again it creates a scenario in which violence against women is gendered and infused with elements of titillation. Violence against female characters should never be sexy.”

I saw her trying to draw clear lines all throughout her NYU talk, and I could sense what a fraught endeavour that was. As easy as she had suggested some of the changes in gaming could be, so much of this is likely to be controversial — and not just because someone might be sexist. How do you balance creators’ freedom with the need or desire to open a game up to a broader audience? How do you assess which portrayals of women in games attract or repel male or female gamers? How do we truly determine the impact of the characters we see or control on how we relate to those characters or view the world?

Sarkeesian didn’t lay out those questions, but those are the ones implicit in her critique. Those are the ones that supporters and critics of her views on women in games are likely to debate for a long time to come. Little of this is bound to be easy, and each of her eight requests are likely to stir debate about what gamers want, what developers can or should do, and what makes for better video games that more people will enjoy playing.

Comments

296 responses to “How Anita Sarkeesian Wants Video Games To Change”

“If you agree with her worldview, you’re likely with her on many or all of these eight things. If not, well, you’re unlikely to see much here you can back.”

Agreed.

Exactly, if you like watching women’s sports, you’ll find a way to watch them, regardless of whether or not they get equal screen time with men’s sports (there’s a commercial reason for that). Anita finds it hard to deviate from her ‘one size fits all’ approach to feminism and also finds it hard to articulate reasonable goals for developers. I overheard some girls on the bus this morning expounding over how hot and beautiful one of their teachers was. Goes to show that there is no gender barrier to objectification. And who decided that objectification is morally wrong? As @bluxy says below – it’s fantasy!

I think the point is not that objectification should be done away with altogether, but that the portrayal of woman needs to be more balanced rather than *just* objectification. This is a reasonable viewpoint.

You mean that there can be female characters who are objectified as long as there are also female characters who aren’t objectified? I don’t disagree, but I thought we already had that. We’ve got a full spectrum of portrayal from fantasy stuff like Rapelay, Monster Monpiece and other eroge, through Bayonetta and Dead or Alive (powerful AND objectified), to stuff like Mirror’s Edge and Beyond Good and Evil (Anita’s pinup games for female representation). I don’t think Anita has really thought through where she hopes all her efforts will lead to if successful. Do we only want games where women have agency, are realistically proportioned and modestly dressed? I have a feeling that Anita might, in theory. My point is it doesn’t have to be one or the other. Sorry for the rant – it wasn’t necessarily all in response to your post.

When you are trying to say nothing needs to change and that there is already good female representation and you need to head back to 2003 and 2008 for good examples, I think that is a problem.

well that’s unfair, ok how bout these: New Lara croft, Cassandra, ellie, and I’m not sure when you think the last Bayonetta came out. These are also just off the top of my head. Now name me 4 male leads who aren’t tough guys motivated by more than revenge/justice. The point is not that they don’t exist, they’re just less of them.

I think that what needs to change is the attitude of some people who, as soon as they hear that Anita or Zoe or Brianna are doing their thing to promote women making and being positively represented in video games, respond with a cacophony of ‘Anita is ruining video games’. That’s obviously not true. I think that promoting an environment where women are free to work in video games, where video games portraying women as positive and pro-active role models, is an important goal. What I disagree with is the idea that promoting the aforementioned goals necessarily implies that portraying women IN ANY OTHER WAY should be frowned upon. To do so suggests that men are incapable of distinguishing the fantasy of objectification in video games from the way women should be treated in real life. Imagine if we suggested that showing a film like 50 Shades of Gray should be banned because it might cause women to be more submissive to abuse in real life? Women would, quite rightly, scoff at the idea that they didn’t have enough intelligence to separate fantasy and reality.

I agree that the attitude needs to change. I don’t think most feminists want no sexuality in games and having seductive, alluring female isn’t a bad thing. But it shouldn’t be the only thing, and ‘girl’ shouldn’t be a character type.

If the only male character in games was the bumbling I tried but couldn’t get things quite right Dad character that is prevalent in lots of advertising I would be arguing for better male representation is games. Hell I have argued for that better representation of males (well specifically fathers) in advertising and that is something I don’t care about.

The portrayal of demographics does flow through culture and shape peoples perceptions, which is why a wide range of real characters rather than stereo types is something to aspire to. At the moment to me is seems like games have the same type of stereo typing of women as the 1960s had of the Chinese. There was only one type of Chinese character and that was how many people perceived them.

On the topic of “good female characters” by Anita’s definition, how in the hell is Chell from Portal a “good” female character. She has no lines, she has one appearance at the very start of the game that is easy to miss, and she does nothing remotely to identify herself as a woman (some may claim that is a good thing but equality and mature depiction surely isn’t “make women like men, or make everyone genderless figures”, right?). She’s nothing more than a floating gadget moving through space.

Yeah, I don’t know. Maybe it’s the simple fact that she is female and is not the object in the eyes of the player? She, for what it’s worth, has agency over her own destiny. I do agree with you that the impact she (as a female) has on the player is minimal.

I firstly disagree that women in video games are exclusively portrayed in an objectified manner. For example, Lara Croft, Anya (Gears of War) and Ellie (The Last of Us) are all the complete opposite. There’s three games off the top of my head, and they aren’t from the last few years, that is an 18 year period between the oldest and most recent.

Secondly, I don’t think that everybody’s quarrel with Anita is that her opinions will particularly affect them, it’s just that gamers* don’t particularly like hearing such seemingly narrow minded opinions from someone who openly admits she herself isn’t much of a gamer*.

It’s one thing to notice flaws within something, but if you can’t admit there is an equal amount of positives – whilst also completely ignoring the equal amount of flaws in relevant counterparts (i.e male protagonists being equally objectified with masculine personalities and muscular modelling etc) then you’ll have a hard time with anyone in your target audience actually listening to what you have to say.

Gamers*: Not the broad terminology – i.e ranging from the occasional candy crush player to the hardcore “Pro” gamer – but a person who has both sufficient knowledge and experience in video games on a range of platforms.

Good article. All common sense suggestions.

I can agree with some of this but some of it is just oh stop sexualising female characters and well while it’s done to much i believe it still should be done a little heck sexualize men in some videogames while your at it.

Games should be made for a specific group of people.

If you want a game where girls have big boobs and are in bikini’s then it should exist

If you want a game with buff men who look good then that should exist also.

get over it… its called fantasy

To make these changes would require an immense amount of effort on the developers part for such a small minority, it would be irresponsible as a company to

A. Stop using the age old “Sex sells” approach

B. Fund all these changes detailing as small things as how a character sits

I agree they do portray women in games as useless characters only there for the male lead role but to be completely realistic.. its just not business to do so and that’s all these company’s are.. businesses.

For the record (and this is the only thing I’m going to say about this): women are not a ‘small minority’. They actually make up 51% of the population.

Thanks for the hot tip Shane but it was in relevance to women gamers who are upset by how they’re portrayed in games.. I thought that was kinda obvious but next time I’ll add little drawings so you can follow 😉

that sort of logic just broke my brain, just because some people arent as politically minded or vocal that doesnt mean they dont want change or will appreciate it, some times we dont know how much something is broken until we see a change.

Im not a female and I am not one who is political invested to how woman are portrayed, as much as others. That doesnt me I dont want change, nor am I uninterested. That doesnt mean I dont care about the ‘politics’ of it all, it just means my focus is elesewhere.

It all comes down to one simple fact… I want the woman in my life to be treated with mutual respect and not have to put up with stupid narrowminded idiots who dont want change simply because it doesnt affect them.

Here’s a few thoughts for you @caterpillarmitch:

Do you think the percentage of women gamers would change if the content of the games was changed to be more accommodating to women and less directed at men/boys?

(I think it would)Would the percentage of women gamers increase if there were more female characters (both playable and combatant) in games?

(I think it would)Hypothetically, if the content of games were changed so that women gamers grew to become 50% of all gamers (to roughly match the makeup of the global population), do you think the proportion of male gamers that stop gaming because of the change in content would be more, or less than the proportion of women gamers that have taken up gaming because of the change in content?

(I think it would be significantly less – meaning we would have a crap load more gamers)Lastly – If the content of games changed to better represent females, and the gaming population of the world increased as a result of the additional females picking up a controller or keyboard/mouse – who is this adversely impacting, is it bad for business, and is it bad for equality?

(I’d say the only people who wouldn’t come off better are the bone heads that can’t handle more appropriate content regarding women).So I’m just not sure the “immense amount of effort” it would require of a developer would actually be irresponsible for any gaming company, if it would result in greater sales to a greater population of gamers.

Dude, gamers were already 48% women in 2013 http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/08/22/adult-women-gamers-outnumber-teenage-boys/

Not to trash your other points, because I basically agree with the sentiment, but I think the variety in games is already at a point where anyone, man, woman, boy or girl, can find something cool to play. I encourage any devs who want to make games like Anita wants, but it shouldn’t be the only option.

That figure is not accurate for the “hardcore” market unfortunately. That’s why you see games on PC and mobile embracing that diversity while triple A releases remain fixated on the young male demographic.

Yeah that’s probably right. So young males are prepared to pay more to get titillated by objectified women in video games. I firmly believe that if women wanted to pay more to have empowered female protagonists, you’d see a shift in the market. Anita is arguing that if you create the supply then you’d get the demand. I think that there is room for a middle ground – such as kickstarter projects with Anita’s seal of approval, for example. If games such as Star Citizen, or even to a lesser degree Shadowrun Returns can get crowd-funded, why can’t Anita and a developer work together to campaign for the type of game that Anita wants? If the market is there, then the project will be funded. Otherwise, Anita would have us suffer the equivalent of positive discrimination, where changes are made for changes’ sake, without having the popular support or the market to support them.

To what degree is that true *because* the “hardcore” games are fixated on the young male demographic?

There have been AAA games that were popular with women – for example, The Sims. Perhaps if somebody was willing to risk the budget there would be more.

Unfortunately that’s probably a large part of the problem – the money men for AAA games want to stick with what they know works, and what they know works is not particularly feminist in approach.

Not only that, it results in overly safe games, period. All we get are endless sequels and copies instead of new IPs, that could champion new, diverse protagonists and gameplay ideas. But yeah, can’t do anything with old scared white dudes holding the purse strings.

My position this entire time has not been “there’s not a problem”, more “there is a problem, how do you propose we solve it, within the current rules of the games industry”

How do you propose getting the funding to create this big budget game while also making back enough money to justify this game?

“‘Push the envelope’? You know who uses that phrase? People who don’t have the guts or the brains to work inside the system: letter writers! radicals! Howard Dean!” – Jack Donaghy, 30 Rock

@geometrics Increasing awareness of the problem is an important step. When everyone agrees that powerful female role models are important in games, it will be a lot easier for developers to create them. The problem is not that boys are cooler in video games, and we’re trying to get the developers to make uncool characters. The problem isn’t even that boys sell better. The problem is that people really believe that boys belong in the hot seat and that girl characters aren’t as cool. Why don’t female characters sell as well? Because our culture has pushed the idea that male characters are cool/powerful, while female characters are sexy.

Why do some men have a problem with being a female character? I don’t intend to be offensive… but isn’t it kind of weird? Do men fear that they’ll become more girly if they play games with a female character? Do they really believe boys are cooler? Even men who are really extremely sexist should prefer to look at the back end of a woman… right? Would it be offensive to suggest that there may be some underlying, subconscious homosexuality? Society doesn’t let them express it without changing their views on life, or without denying their heterosexual side. But it’s imaginable that deep down, they enjoy engaging as a male character (and only a male character) because it provides them the homosexual satisfaction that they are denied by being 100% heterosexual.

Perhaps the most likely/common reason is that boys want to play male characters because they themselves are male, and they relate better to, and feel empowered by, a character that they can relate to. I say, good for them! That’s great. But girls deserve the same, without having to be told that what makes a women great is the color pink and a lot of cleavage, etc, etc.

Anyhow, people like Anita Sarkeesian are solving this problem by peeing in the pool so to speak. She is sometimes hated for what she’s pointing out, but there’s truth behind it. Pretty soon, people are gonna see that there’s something wrong. All this internet hate is gonna subside, and the truth of the matter will be what sticks around, and culture will adjust.

My comment was purely about the business side and how it would be unprofitable therefore unlikely to happen.

The small minority I was talking about is people who would not buy a game because of the sexism – Again business orientated.

Good business doesn’t justify creating a lousy culture.

The fact that boys sell well causes boys to sell. The fact that boys sell causes boys to sell well. It has to be stopped, and it has to be stopped by responsible businesses.

Create the culture, and the business will follow.

Women are making up a larger portion of “gamers” each year though.

And changing the stereotyping of women in games isn’t just for the females anyway.

I’d like to see more realistic, or at least more prominent female characters, and I’m a gay man. I’m sure there’s plenty of other men who feel the same. The amount of people who would like to see a change isn’t such a minority…

Saying that it’d require an immense amount of effort also is also, simply, not true.

Games such as Tomb Raider, Mirrors Edge, Final Fantasy XIII, and Beyond Good and Evil prove how easy it is to make a more prominent female lead while still remaining both profitable and enjoyable (your experience with enjoyable may vary).

cringe

Games are a product, not a utility. In the same way Men make up a fraction of Harper’s Bazaar readers, female gamers make up a small number of hardcore game consumers.

According to NPD’s Core gaming 2013 report:

The HD shooter audience is 78 percent male.

The HD action game audience is 80 percent male.

The HD sports game audience is 85 percent male.

If I called up Cosmopolitan and told them to stop misrepresenting males as two-dimensional, steak shovelling, cheating, emotionally stunted morons, and make more articles about male interests, they would laugh and hang up. I am not their target demographic, I do not pay their bills, and as such, I am not a major consideration for their creative and marketing decisions.

If female consumers want more decisions based on their wants and needs in gaming, they need to stop being loud and start being numerous. That or buy 2 to 3 copies of every game that comes out each, although, with this current climate of re-releases and remasters, that might not be such a lofty goal after all.

—

That is not to say there ISN’T a problem with the way women are generally portrayed in video games, but this is much needed information for those who say “half the population is female” or “50% of gamers are female”. Those are misleading figures at best, completely incorrect at worst.

The only relevant discussion is WHY so few women play these kinds of games and while the current dialogue is ‘I dunno, GIRL BITS’ the true answer is probably a combination of internal presentation of female-friendly content and external enculturation away from them.

Taken to the extreme, it would be like petitioning Playboy magazine to start showing more nude male models alongside the female models. You’d say, what the hell? Why don’t those who want nude males just go and buy Playgirl or something similar. The ‘market’ for videogames is more diverse and fragmented than Anita would have us believe. Some people want objectified females; some people want powerful female player characters – it doesn’t have to be a zero sum game.

I agree.

I am a little over seeing people point out population is 50% female or gamer’s are 48% female but overlook the target demographic for the game in question.

Specific Games are targeted at a specific demographic. If that target demographic is males between 16-35 in the US you can be sure the avatar or character makeup is going to try and be as close to that demographic as possible. Ever wonder why shooter/action games with 4 characters have 2 white males, one black male and a girl. If you have a set of characters your going to have half them represent the largest portion of your target demographic (white males between 18-35) then you will have the other 2 match the next highest but mix them so you the non target have something to connect with.

Is it right from an equality POV… I dont know. Personally dont think it really matters to the people making the decisions. Its business. If you want to change it, you need to show a fiscal reason for the change and unfortunately its going to have to be more than “it wont make a difference”. Right now they have the dude bro games that make shit tonnes of money and they aren’t going to risk the tried and true formula for making shit tonnes of money without the potential for making even more money.

Not saying this is right or how it should be, but this is the real world where business are there to make money. You want a person to change, reason with them and explain why. You want a company or business to change, show how it improves the bottom line.

Studies have actually shown that men are far more adverse to trying products perceived to be for women than women are in trying products for men. A game with less than a majority of males could be perceived this way by young, insecure, teenage boys, definitely.

Even psychology and consumer behaviour is on the side of these companies playing it safe.

But the difference here is that you have cosmo and you have playboy. Different magazines targeting a different market at each end of the spectrum. Currently AAA games are all at the playboy end with nothing at the cosmo end.

http://www.forbes.com/sites/insertcoin/2014/07/17/kim-kardashian-may-make-85-million-from-her-video-game/

You missed the point mate. They are saying that the AAA games are the playboy. AAA games in general are purchased and played more by men than by women.

I understood the point but disagree that AAA games need to be playboy. That is the case now but there is no reason that AAA games can’t be the magazines as a whole with different types appealing to different demographics

FPS might always be the playboy of AAA games and maybe a style adventure games become the cosmo and are more female focused, or at least with a much large female player base.

I would love to see an end to the “sex sells” approach. I don’t buy video games for my penis.

And if there already IS a sitting animation (hell, they even put in a dancing animation), then surely it shouldn’t be that hard to get it right.

It would need to be all movement, actual work in female character development, more talented voice actors, vast changes to character models / design and clothes.

All these things would be amazing but at the same time I am realistic that these company’s do not care.. like one bit about who they make people feel unless its affecting their profit.

I think the point made here is that all that work is already being done. They are already getting different models, different animations, VA, clothes, etc…

But rather than have the same brief given to the male mocap actor (tough and confident soldier, angry and aggressive thug, relaxed business man) they are getting the “Walk sexy, sit seductively, etc)

Teh actual cost to the business is minimal, and if they can get a larger female player base that greatly improves the profitability. Not turning off the number of women who see these sort of things and think gaming isn’t for them is a much greater potential revenue stream than the number of guys who would refuse to buy a game because the female characters aren’t sexualised enough for them.

You say that, but why then are shitty games like Game of War Fire Age or Evony marketed like they are? Because if they didn’t market themselves that way then the number of players would drop off dramatically. They don’t market themselves like that without reason.

Using sex to sell a shitty product is a different thing, they are using sex because that is all that they have.

If tomb raider launched with evony style ads I would never have bought it. If the divsion starts a massive campaign of sex sells type marketing campaign it will drop from my most anticipated game to one I don’t want.

I’m not denying that sex sells, that is basically a marketing truth. What I am saying is that is your game isn’t using that sexualised content to sell, why do you have sexualised content in there. Having actual female characters (aka dragon age) is much more likely to increase the sales of your game, than having a bunch of sexualised placeholder characters. Of course this only hold true if you are selling a game based on the story/gameplay/mechanics not on the amount of boob jiggle you have

I used Evony et al as extreme examples, but you only have to look at the poses of female characters on the covers of games (or film posters) to see that there is an element, more or less subtle, of sexual marketing present in a lot of games and films. For example – Nilin in Remember Me. Check out her pose http://static4.gamespot.com/uploads/scale_medium/mig/7/2/3/9/2227239-rememberme.jpg

Not many dudes have this kind of pose (some do). They are all facing the camera and looking grim and holding weapons. Look at Lightning’s pose http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/47/Final_Fantasy_XIII_EU_box_art.jpg She’s got a bare leg at an awkward angle, torso tilted to show off her breasts, etc.

I’d be interested to see a survey of female gamers to see how purchasing decisions are made and whether the possibility of playing as a female has any bearing on them. The closest I’ve seen is an interview with the developer of Puppeteer http://kotaku.com/a-game-creators-argument-for-only-letting-you-play-as-756362517 where he said that when testing the game on kids (boys and girls) not one of the girls said anything about the fact that the protagonist was male. You might say that’s just because of the ingrained social expectations that men are expected to take the lead, but that is less and less likely these days, especially in first world countries.

Plenty of talented female voice actors out there. Jennifer Hale, for example, blew away Mark Meer’s performance as Captain Shephard. And if companies can find the time and resources to properly animate and characterise alien races of all shapes and sizes, then doing the same for the female half of the population shouldn’t be all that hard! To further prove my point, some developers already are doing it; inFamous: First Light is a good example. Beyond Good and Evil came out two console generations ago, but was still able to do it. It can be done. No excuses for lazy developers.

Jennifer Hale wasn’t ideal for 80% of the female Shepard creations. The game gives you many options to make young Shepards, yet only a clearly 30+ voice for her.

I found her voice acting to be incredibly grating for my Shepard, and personally only really saw it working for a minority of Shepards. And the forums tend to show players choosing younger looking female shepards overall. That is, the 18% of all Mass Effect players who chose her http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2011-07-20-bioware-18-percent-play-mass-effect-as-femshep

Good voice acting? Sure. Right casting? Maaaaybe not.

Shephard is the commander of the Normandy, and first human Spectre. To get that kind of responsibility, where the lives of a war spaceship crew are in your hands, would indicate years of military experience and slowly gained trust from your superiors over time. So for me, personally, Shephard being 30 makes good sense.

I agree with that reasoning. But when they put character creation in the hands of the player, they need to accommodate for both Attractiveness Bias and Baby-Face Bias. They are two design and psychological principles that state people want to see younger looking, more attractive people in their games. Our warped psyches see them as more intelligent, competent, moral and sociable than less attractive people.

People will, by virtue of human nature and first world culture, aim for the younger, prettier model. Not to mention the issue with giving people the options to change their face but not their voice being pretty restrictive and contradictory game design.

If she was much older than 30 she would not have been chosen to be a spectre!

Here’s the problem I see with the sitting animation. The male one sits with his legs apart so his crotch is in view. Can you imagine the outrage if a female character was depicted that way? This is unfortunately one of those lose-lose situations. If you have the female sitting the same way it’s sexist because it emphasizes her crotch, if you make her sit “demurely” you’re criticized because she apparently doesn’t sit like a hardened space marine.

Such a small minority? Srsly? More than 50% of the population dude.

Look I love games too. But I can’t be the only one who gets the shits when a chick going into combat is wearing high heels. It’s stupid and unnecessary.

What about when a guy is wearing a super tight singlet or carrying, like, 50 guns on his back?

It’s okay to reinforce negative stereotypes about male violence, though…

Nowhere in the article did it say Sarkeesian thought negative male stereotypes were awesome.

In fact, I’d think a large number of people who would like to see less negative female stereotypes in games would also like less negative male stereotypes.

Male power fantasy, not women’s sexual fantasy.

And seriously? “Negative stereotypes about male violence”? Jesus. Pull your head in.

I can guarantee you both my mother and my girlfriend, part of that “more than 50% of the population” don’t care at all about this. They will never be aware of any perceived issue, will never put money into the industry, never observe any changes, neither support or object to either side of the debate.

So why should developers put money into making them happy?

Can’t see how it’s ‘irresponsible’ to resist using sex to sell your game. If anything it’s the opposite.

I think their point is that it is irresponsible to the shareholders to do so if that will reduce profits

In all honesty, would you buy a game that used sex appeal to shift copies? Would you want to see Zelda start showing off cleavage? Would X-Com be better if the female soldiers ran around in skimpy outfits?

Zelda’s a dude, guy. He’s the one on the box with the sword.

What, so now a guy can’t show off his moobs. What has the world come to

Not sure if serious…

Actually the guy on the front is Link. Zelda is the princess.

Hahaha! Pls Google Zelda if serious.

http://i1.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/facebook/000/282/221/115.jpg

haha. If I wasn’t already married….

Developers are already paying for two sets of mo-cap and animation for the male and female animations.

It would cost the same to tell the mocap actors to do something else, or the artists and animators to design different costumes etc. next time.

The business question is Does having sexed up characters scare off female gamers more than not having sexed up characters scares off male gamers?

“Happily, this is another easy one to solve,” she said, when lamenting the sexualised grunting that she often hears from female game characters who are supposedly engaged in combat.

I wonder if she has ever watched Womens Tennis 😛

Yes but female tennis players are portraying women in an unrealistic way

Yes, nobody should grunt that loudly even when they are really enjoying themselves.

Dunno about you, but I definitely don’t find that sort of grunt sexy.

I think she would be happy if a female character swinging a sword sounded more like Sharapova and less like Meg Ryan in When harry met sally

Which game is that?

That point about X-Com made a lot of sense. Male or female, same body armour. I never even thought about that while playing, and it seems like sensible body armour shouldn’t be too much to ask for.

Sure. I think having demure men and scantily-clad women is a little unbalanced unless the plot calls for it. Why not have buff and hunky dudes along with the voluptuous women – so everyone can get their jollies, regardless of gender or sexual orientation!? Titillation for all!

It beats me why magazines like Women’s Weekly and New Idea sometimes put bikini pics on the cover though. Seems to me like women like ogling celebrities in bikinis just as much as men do. That was just a random remark – not sure how it ties in here.

ugh.

I completely agree that there should be a stronger presence of women of more substance than the ‘girl’ or the ‘model’ in games. As well as games having more diversity in general. But I don’t agree that there should be rules put in place that state “one must never, ever do X”.

If videogames are ever to be taken seriously as an art or media form it can’t adhere to rules of such a strict framework.

If videogames are ever to be taken seriously as an artform they need to grow, change and have criticism accepted. She’s not setting rules.

Thankyou!

I agree, I don’t discount what she’s saying at all. She’s coming up with helpful suggestions after making critical judgements. But saying that, she’s only one critic, one person, and what she’s saying shouldn’t be taken as gospel.

While I understand her point it’s disingenous to completely disregard this and brush it off. Men are definitely sexualised in games, though *absolutely* not to the degree women are. But just because it’s not to the same degree does not make it acceptable still. Gears of War for instance, or even DOA games, enjoy promoting roid-bound men with giant chests, heaving muscles etc etc. But, that being said, of course DOA is packed full of giant breasted porn star women, so I’m not ignoring that at all. Just simply stating, that by her stating ‘she doesn’t buy it’ she very much glosses over the idea, removes any credibility of it, says it simply ‘doesn’t exist’ and dilutes any potential issue of bad representation of a gender…

Kind of sounds familiar.

She’s a critic. Critics cherrypick what they want and ignore other stuff in order to put their point across in a stronger light. Age old trick

Plus, since Kickstarter, which she still has not delivered on, she is also a salesperson. She’s selling her product.

Anonymous commenters cherrypick far more though :/

How many people seriously consider Marcus or Dom sexually attractive? I’m pretty sure the list consists of a handful of women, gay men and Vincent McMahon.

Garrus from Mass Effect has a much, much larger female fanbase than any of the examples people tend to throw out there as sexualised men.

More importantly, the two points are not equal even if people did accept those examples of men being sexualised. The majority of female characters in games exist to be “the chick”, the romance option or someone to be rescued and most are sexualised. On the other hand, male characters run the full gamut. There’s antagonists, protagonists, damsels and heroes. There’s the goofy guy, the serious guy, the scientist and the jock. Some are sexualised but most are not.

It’s a completely false dichotomy so Anita is completely right to dismiss it. More importantly, it’s not the point she’s making. If someone is talking about famine in Africa, that doesn’t mean it’s time to start talking about poverty in your city.

dude, no. If it’s not the point she’s making and doesn’t need to address it’s existence not how “equal” it is, then the omission of women from a panel would be cool when it ain’t. What she’s doing is diluting the potential affect of media on boys. She could have said that it isn’t what she’s here to talk about since it’s another conversation, she flat-out refused it’s existence and that’s damn wrong. If you don’t think representation in media affects boys you’re wrong. Repeating and espousing a momentously generalised argument doesn’t change that. I’m also trying to understand why anyone would believe acknowledging something outside your argument harms it.

The word “representation” is also not exclusive to sexualised representation. It can project any look, behaviour, race, gender or ideal as “true” and this affects everyone. Whether girls find them sexually attractive is besides the point, the expectation for boys to act a certain type of “tough” directly feeds into the sexism inherent in the portrayal of women. Changing the representation of women doesn’t address this, it doesn’t fix the attitude boys may have towards them because the entire argument has been dismissed. It’s not in the same way as women but it is entirely ignorant to pretend it doesn’t exist for the benefit of your argument when it is so intricately interwoven.

Generalising the issue to a laughable degree does nothing for change. Women might have some great experiences where they’re represented the way they want to be and that’s a noble goal but I see it as being short-lived or fraught with more conflict if you don’t also address the attitudes and false truths given to boys as well. I’m of the opinion that hopefully a change in women’s representation will lead to an inevitable change in the way men and boys see or react to women (as well as their own gender). It goes both ways. You can’t say the representation of men, historically in video games hasn’t directly fed their attitudes towards the reasonable arguments of women in gaming.

Games can and should address both points. Why does Anita have to?

Because its her responsibility as a champion for change in gender portrayal and diversity to understand that men and women are irrevocably linked. And that you cannot separate one gender’s identity from the other’s.

They are separate issues that can be addressed by similar means. She’s not a champion for change in gender portrayal, she’s a champion for better portrayal of women.

People are not obligated to broaden their scope, especially when they’re struggling to find success with a narrow one.

But when you are talking about depiction of women in video-games, you are talking about men. When you are talking about sexism, you are talking about the other gender. You cannot talk about one without discussing the other, because in the majority of these arguments, there is one external aggressor (men), and one victim (women). Even though it’s much more complicated than that, that’s what it is generally distilled down into.

Women suck in games because men suck at making games with women in them. That is her main overarching theme. She’s providing instruction for what she wants to see in games to the current developers of games (overwhelmingly male).

They are not separate issues. To fix sexism, you need to talk about and directly to the men (and women) who propagate it. You can just agree in a circle with like-minded people. She’s struggling to find success because her scope is too narrow. Her approach is good for generating awareness, but not for generating change.

One of the best responses I’ve ever seen, kudos for nailing it that her scope is far too narrow. Well done.

Yes, the relationships between men and women are irrevocably linked however her speech was about women. Changing overall gender portrayal doesn’t have to be her thing, she’s already got one all mapped out.

As I have said elsewhere. Guys that are huge and strong and muscle bound are not really a woman’s sexual fantasy, but instead are male power fantasies. So basically even they are made that way for dudes. Girls get nothing.

Prove that, prove that beyond a shadow of a doubt. Someone said the idea of ‘male power fantasy’, which no doubt has a basis in reality, but others have taken it and run with it like it’s an absolute and now people cling to it like it’s a holy grail. I think that’s as ridiculous as the idea that no women find muscular men attractive or that all women find muscular men attractive. So I’m sorry but putting forward an absolute like that, is ridiculously unproveable.

lol

The hypocrisy is amazing.

What hypocrisy?

You can blurt all your vitriol as much as you want. But I need hard proof to say anything.

Vitriol implies bitter criticism or malice, there is none, there’s critique, I think you need to learn the definition of it. My critique of it was fair. I asked for that because you attempted to use a blanket statement encompassing everyone. It’s not hypocrisy, it’s you not understanding that when you present a statistic or terminology implying a statistic of some sort, you should back it up with proof or it’s worthless.

Not true. My ex really had a thing for Vin Diesel, and huge, strong and muscle bound are definitely adjectives that you would use to describe him. And if they weren’t attractive stereotypes, why would they keep using The Most Beautiful Man in the Cosmos (or equivalents) on the covers of Romance novels?

Then again People find different body shapes attractive, whether they are male or female. DoA (typically used as ‘sexualised females’) contain sexualised male character. Ein/Hayate and Ryo for those that like the lean muscled pretty boys, Eliot for those that like young boys (Marie Rose could be seen as the female equivalent of him following on a game and revision later), Dennis Rodma… er… Zack for those that like his particular body, Leon for those that like the mysterious muscled Russian… Gen Fu and Bass were pretty much the odd ones out in that they was pretty much the only non-sexualised character of either gender. (Although I’m sure theres someone that has a thing for Hulk Hogan)

It is. I’ve had the privilege of working in a number of school and young boys, just as much as girls suffer from image issues. I’ve seen boys as young as 12 being harassed and assaulted for no other reason than they seemed to like sports and he had a Nintendo DS. I’ve seen boys in classes conspire to omit the “gay kid” from the creation of every working group. I’ve seen a boy consistently use sexual violence as a story element in his drama work only to find out later that there was a tragic reason for this. What is expected of masculinity is a heavy burden to carry for some boys.

Whether her comments on this issue are simply wrong or entirely misguided, it is at the very least damaging to boys like these. Yes, girls have it rough but I shouldn’t have to say that for merely discussing someone else. It doesn’t matter how widespread it is, we don’t ignore one to focus on the other. The issue of representation in media affects everyone. The portrayal of men affect women and the portrayal of women also affects men. It’s these little ignorant things and her hard and fast stance that boys like the ones I mentioned above are worthless in her argument.

She’s a woman, so she speaks from a female perspective. Unrealistic body types for men in games may be bad too, but so far no bloke has bothered to get up and do anything about like she has.

I’m a guy but I wouldn’t tell someone of a different gender, religion, sexual orientation or cultural background that their problems don’t exist just because it’s not my perspective.

She doesn’t say that their problems don’t exist. She doesn’t talk about those issues because her fight is about the depiction of women. She never claimed to be the champion for religious intolerance, so why would anyone expect her to bring it up?

i think saying “she doesnt buy it” means she doesn’t think it exist

It all revolves around the incredibly reductionist idea that “power” only means physical strength and an ability to pulverise your enemies. Which is completely incorrect. There are endless forms of power in our world.

A male power fantasy (ignoring the laughable notion of every male having the same power fantasy) would be rather different based on upbringing, interests, motivations, etc. than a female power fantasy. For some women, being able to get men to do things for them by exploiting their sexuality IS power. For some men, a power fantasy is being an amazing father to their children. Some women want financial power, some men want the power to make a mean pot roast.

Furthermore, to say a character like Joel in The Last Of Us has any real power at all is laughable.

Here’s a man, forced to do a job by a woman who overruled his misgivings, following the orders of another woman who leads an entire resistance movement and must now lay his life on the line for a young girl at every opportunity.

Joel has no choice in where he goes and what he does until the very end of the game, and while he can kill others with ease, he never has any say in whether he wants to fight or not. For a man who is a “power fantasy”, dude sure doesn’t seem to have all that much power to me.

And women can’t flock in droves to Buzzfeed for the latest Ryan Gosling eyecandy article and then say that the shirtless sweaty dudes in fighting games couldn’t possibly be for the benefit of women. Get your story straight people.

Also, breasts move in-game because that’s what they do in real life. There’s literally a billion dollar sports-bra industry that revolves around this fact. Penises however, tend to stay where they are, unless you’re one of those commando types.

In Street Fighter, there is exactly one example I can think of where there’s a shirtless pretty boy. It’s Vega. The villainous narcissist. I don’t know how many women you know but most of them are not flocking to look at Ken and Ryu (and definitely not Rufus, Dhalsim or E. Honda). Whereas practically all of the female characters are considered attractive.

Also, I’d just like to point out the contradiction between:

It’s abundantly clear that Ellie becomes his proxy child and his papa wolf attitude towards her as the game goes on means that there’s a clear example of real power that you’ve already mentioned.

You’re right, I misspoke. By “real”, I meant, the stereotypical notion of power.

As for shirtless pretty boys, check out Soul Calibur and Dead Or Alive.

Go through the cast of any fighting game. Do a rough count of attractive men and attractive women. I’d wager that almost all of the women and fewer than half the men would make the count.

Do you not see the problem there? That there is much more diversity in male representation than female representation? When the problem is that most women in games are sexualised, the fact that some men in games are sexualised does not balance it out.

Go through a crowded street in a public space. Do a rough count of what people find attractive. I’d wager that almost all of them will tell you something different.

There’s more men in triple A games because there are more men playing and developing triple A games. Those are the facts. Women writing men never goes well, men writing women isn’t any better. You are confusing the effect for the cause. We need more women making and playing Triple A games if we want to see positive change.

That is, of course, assuming that there is a real diversity in male representation in games. Which is debatable.

And there’s no good reason for that. If you think that’s the root cause to this issue, then you’re free to argue that.

To Kill a Mockingbird was written by a woman. J.K. Rowling wrote Harry Potter, there are several great male characters in there. Terry Pratchett wrote the Discworld books, there are numerous great female characters in there. Joss Whedon is pretty well known for his portrayal of women and you can even argue that Quentin Tarantino does a pretty good job (within the bizarre context of his movies).

No good reason for that? Yes there is. More males are studying games development, and more are getting jobs in games development. That’s a straightforward reason for why that’s the case. If you mean there’s no good reason for the diversity to be skewed, my argument is “is there a good reason for it not to be skewed?” It’s about interest, and clearly men have more interest in triple a development and games on average than women. The numbers do not lie.

There’s more female nannies than male nannies. Is that to be viewed as some sort of injustice to be corrected or a result of different priorities and interests?

As for the writers you listed, yes you’re right, but show me that kind of writing talent in the games industry. There are very few amazing writers in games, because any other medium would be far more suited to their talents and far less constrictive based on financial concerns.

@geometrics Okay, is there any good reason why men should be more interested in game development than women? Games are games. Playing is a human activity.

@trjn From my perspective, absolutely not. But clearly most women disagree with me. It’s not a case of “they aren’t allowed”, it’s a case of “they simply aren’t doing it”.

I for one would love to see more women in games development, but they aren’t applying for it, they aren’t studying it, and when it comes to 80% of all HD action players being male, they clearly aren’t even playing it. Not to mention the tiny 18% of Mass Effect players choosing to play as female Shepard. This is what happens when you make options for women in Triple A titles; they largely go to waste.

@geometrics Mass Effect sold millions of copies. 18% of several million is a pretty large number, hardly a waste. Not only that, people are inherently lazy. Got the numbers for how many people stuck with the default Shepard?

@trjn I do indeed:

“Silverman went on to say that 13 per cent of fans opt for the pre-built Shepard character, male or female. That means the remaining 83 per cent choose to customise their own looks, class and abilities.”

Source, if you want to check:

http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2011-07-20-bioware-18-percent-play-mass-effect-as-femshep

@geometrics 1 in 5 players played Femshep. I was astounded that I could save the universe and not be burly default Manshep. I would say that’s not a waste.

@freya

On one hand I agree with you. But ultimately as a very story orientated game with many fleshed out characters and motivations, I felt it was disappointing that Shepard was so flat and generic. His/Her responses are largely the same to most of the dialogue, and as a result Shepard didn’t really represent a female position at all. She was just re-reading lines said by a male actor before her. There are a few things here and there were the lines are different, but ultimately the opportunity for choice just served to create a weaker protagonist.

I would have preferred one Shepard, be it male or female, that they stuck to. Because amongst the rich, three-dimensional characters of the Normandy, Shepard’s a cardboard cut out.

—

And it’d really come down to cost/benefit as to whether or not female Shepard was “a waste” as I put it, perhaps a little too harshly. If it cost more for the female option to be in the game than it made them back, the publishers wouldn’t be happy. Although one could argue that the goodwill earned by the developer for doing so is priceless, so who knows?

@geometrics Um, Jennifer Hale did a much better job than Mark Meer at bringing emotion and interest to Shepherd. Also, Shepherd is meant to be a cardboard cutout because she’s essentially the player avatar. You make the choices, you shape who she is. If she has too much personality before you make decisions, you don’t get invested in her over the course of three games.

@freya Yeah, the performance was better, but there wasn’t much scope to be a character outside of a gender-neutral, female skin, or a gender neutral male skin. Sure, you can bang different people, but that was about it.

There was no actual feminine characterisation outside of those sexual relationships. If you were just reading the dialogue from a blank screen, it’d be tough, aside from pronouns, to discern which gender Shepard was. That’s what I mean.

@geometrics I am not sure what your point is? Mine is that it was immensely powerful to have the option to play this three dimensional character who is super rad and awesome and saves the universe and happens to be able to look and sound a bit like me. She doesn’t need to have any more feminine characteristics than she did – she still comes across as a woman. And a badass, which is probably the more important part.

@freya

My point is that Shepard specifically is not a three-dimensional character (at least compared to the companion characters) because of the choice to allow for choice in character gender. You already said:

So I don’t understand why now you’re saying she is three-dimensional after all.

I would much rather a female Shepard than a choice between male and female, because then the writers could commit to her being a woman and really flesh her out with a gendered identity, to the extent of a Joel or Ellie or pretty much any character in The Last Of Us.

But I think the biggest question is why? Why is it important for the character on screen to look and sound “a bit like you”? How does that negatively impact your experience if you can’t relate to someone who is a male, or a different race? And more importantly, what does it say about you that you seemingly struggle to connect with a character who isn’t the same gender or appearance as you?

You can appreciate films even though the characters clearly are not you, right? I’m not trying to antagonise you or anything, I just hear that “looks like me = good” reasoning a lot and never really understood the position.

Choice is a cornerstone of the medium, but choice over the actual narrative only serves to dilute it. Some times the choice to be female or male rather than a set character might be one small step forward for diversity, but two steps back for storytelling. The overall product might suffer.

Either make a game like Destiny or WOW with full customisation and no character identity, or a game like The Last Of Us or Grand Theft Auto V will no customisation (aside from hairstyles in the latter) and full character identity. No half measures.

It’s not abundantly clear. Whilst I share the sentiment that Joel becomes a father figure I think it’s abundantly clear by his body language coupled with hers as well as the expression on both of their faces that Joel is the only one who believes this. Ellie clearly has a question of how dangerous Joel actually might be and whether going forward he’s actually protecting her or imprisoning her to a degree. Nothing is abundantly clear here and I don’t think projecting allows you to ignore legitimate narrative possibilities.

That’s because Ellie is a well-written character.

Joel has power. It’s much more personal than many typical games but the choice he makes at the end of the game demonstrate it.

The choice he makes is more about his weakness than his power actually. He can’t experience that loss again. He’s too weak to do what’s right, because of his dependence on another person.

You could slice it every different way to support any argument, but you’re right, it’s because The Last Of Us is a well-written piece of fiction. Many of the problems in the depiction of characters in games comes from the fact that most are not well-written, we have the equivalent of the writers of The Expendables as our most celebrated video-game writers.

We’ve set the bar low, and like hammy, lowest common denominator efforts in film, the majority of games (and their characters) are over-simplified and under-written.

I know this isn’t an argument about the ending of The Last Of Us, but I take exception to your characterisation as “too weak to do what’s right”. The choice he’s presented with is a complex ethical dilemma that has been debated for centuries. That’s even assuming the people framing the puzzle to him are correct and not lying.

Apologies for thread derailment.

But that’s the whole point, I don’t even believe that “too weak” position, but I could make it, and you could successfully counter against it. The point is well written characters are deep, they have layers and decisions that could be interpreted a number of ways.

That’s what I loved so much about The Last Of Us. It didn’t treat you like an idiot.

Well there is a couple of points to this. Firstly there is a large number of different body shapes to male characters, the example of overwatch given above. You can see the same thing in something like street fighter. Big characters like Zangreif or Honda, light quick characters like Ken/Ryu and Vega, musle bound boxers, skiny ole Dalsim. While the female characters are all very similar (I haven’t played in a while and this may have improved but I hope you get the point)

The 2nd part is that the roid-bound men with giant chests, heaving muscles are not a huge sexual image for women. Check the sexiest men alive type things and the number one comment will be about their smile or their eyes. A much slimer, cross fit style body is more common and the focus is much more on hair than shaved heads.

Edit: And when you go to lunch between starting a post and actually posting it other people have big long conversation

That of course, is a major generalisation. Numerous times I’ve heard women who like the same thing, eyes, smile etc talk about how they love a guys ‘guns’ (arms) or ‘a great set of pecs’ for instance. So I’m sorry I don’t buy that at all.

*edit* Otherwise things like those Fireman calendars sure as hell wouldn’t be so popular 😉

And yes, massive generalisation and talking mass market context but people like different things

Well I’ve been looking at fireman calendars for ummmmm research for this post

After looking a

one or twoa number pictures from those calendars the body type is much more sports star than body builder. The reference I was making was from the large mass media lists that are selected or voted on by a large segment of the mass market. If a game was to go out and try to sexualise characters they would go for the most dominant sexualised male image and that is more of the fireman than the bodybuilder.As @geometrics there is not a hive-mind that has one type of body size that is ideal. I wasn’t trying to imply that all women find x attractive and all men find y attractive.

The point is that not all men find y attractive or intriguing so I would like to see more than just y type women in games.

Everyone generally would like to see more sizes. I think that’s an absolute must for gaming. Same as instead of predetermined colours, it would be far better to give a colour wheel and allow one to choose their own colour instead.

Yeah, I’m with @weresmurf, was this decided at the annual worldwide women’s meeting? Is it like a hivemind thing where everyone thinks the same thing once it’s decided? Give women more credit than that, and don’t project your personal taste onto the entire population.

You think all men love blondes with fake breasts and excessive make up? Do you think all men look at Hugh Hefner’s wives and say “that’s the ticket”.

You can’t claim that not all women find x attractive and simultaneously say all men find y attractive.

“But she added that some of her critics say that male characters are sexualised, too. She doesn’t buy it, pointing out that it’s common to, say, see female characters’ breasts jiggle and rare to see male characters’ penises do the same.”

Simple test here.