As I arrive at the Virtuality booth at Play Expo Blackpool, things aren’t going too well. The booth has just opened, and the first members of the public to arrive are having a go on Dactyl Nightmare, one of the earliest VR games. But the viewing screen shows that the game world in the right-hand VR pod is being tilted at a crazy angle.

This piece originally appeared on 23 May 2016, on Kotaku UK.

The machine is one of two stand-up Virtuality 1000 VR coin-ops restored by Simon Marston, an enthusiastic VR collector from Leicester. One of the machines Simon has restored is owned by the Retro Computer Museum, where it is on display along with various retro consoles, computers and arcade machines.

Only around 350 of these machines were ever made, and Simon thinks that these two are the only working examples left in the entire world. If one really is kaput, I could be witnessing the last ever two-player game of Dactyl Nightmare.

Simon looks at the customer in the stricken VR pod with concern. “I’m afraid he’s not getting the full experience.” He gestures to a curtain behind the booth. “I think there’s some sort of metal gantry up there. I think it might be interfering with the magnets.”

Magnets? I ask Simon what on earth magnets have to do with VR, and he patiently explains how this vintage Virtuality 1000 series actually works. It’s one of the first generation of VR systems, dating from 1991, and it consists of a massive metal and fibreglass platform featuring a ring that encircles the player. In addition to the VR headset, called a Visette, the player dons a hefty waistbelt — essentially a bumbag with wires trailing out of it that link the headset and gun controller to the machine’s processors. A magnetic transmitter in the ring creates a 3D magnetic field that the player stands within, and receivers in the controller and Visette are used to work out what direction the player is looking and where they’re pointing the gun. It’s an ingenious solution to motion tracking from a time when the Wii was but a twinkle in Nintendo’s eye.

I’m here to have a go on this now-ancient VR technology to see how it compares to the latest VR systems — and whether first-generation VR machines like this deserve the “gimmick” label that some have attached to them.

But right now, it’s looking dicey as to whether I’ll be able to play on the machine at all.

Simon has lifted up the floor of the VR pod and is poking around in its innards, a worried look on his face. “Basically I’m wiggling connections and just hoping,” he says with a frown. He had to take the machine apart to get it out of his garage and transport it up to Blackpool from Leicester, and he’s concerned that the journey may have damaged the sensitive components. “They don’t travel well,” he says.

Simon pokes around in the depths of the Virtuality machine.

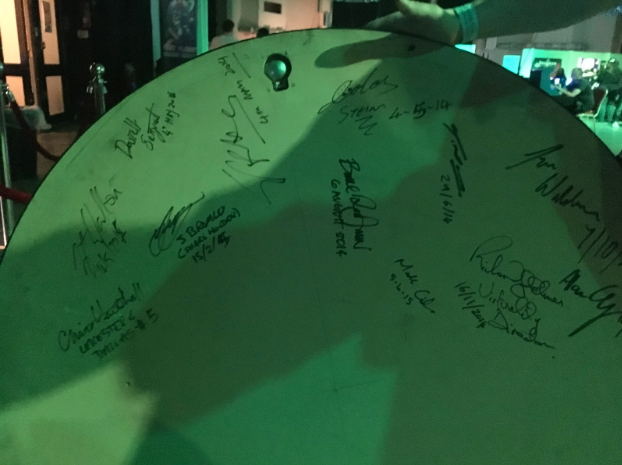

The guts of the machine consists of an Amiga 3000, Commodore’s high-end 32-bit workstation from 1990. (Later Virtuality models ditched the Amiga in favour of a 486 PC.) The wooden underside of the footplate is covered in signatures — Simon explains that he has met various members of W Industries, the company that designed the Virtuality arcade machines, and asked them to sign their creation. “I’ve met more than 12 people who worked at Virtuality, or had something to do with the creation of the machines, from games testers to the company founder and directors. I’ve made quite good friends of a few of the guys too!” The board is currently half covered, but he hopes to fill up the whole thing with signatures someday – and his passion for first-gen VR is infectious.

Simon is collecting signatures from W Industries employees.

After a few reboots, and after moving the machine away from the possible interference, things are looking promising. A grin fills Simon’s face as he wiggles the VR helmet around to show that the game world is now back on the straight and level. “Success!”

Now it’s my turn. I duck under the ring as Simon raises it for me, and he hands me the ‘bumbag’ to put on. Then he passes me the two-button gun controller, explaining the controls for Dactyl Nightmare as he does so, before finally clicking the VR helmet into place over my noggin. It’s noticeably heavier than the latest-generation VR systems at about 3.5kg, compared with about half a kilogram for the Oculus Rift. There’s a definite sense of inertia as I turn my head and the helmet wants to drag it further around. But despite this, it’s surprisingly comfortable.

I’m impressed with the motion tracking, too. As I turn my head to examine the chunky polygon world of Dactyl Nightmare, the machine faithfully updates my point of view, and I can wave the gun around in front of my face. Not bad for an old Amiga. Still, I can’t help but notice the edges of the goggles in my peripheral vision, and the sound effects coming from the headset’s earphones are noticeably hissy — a glitch caused by a short that Simon didn’t have time to fix before the show.

Your correspondent braves the world of 1990s VR.

Once the game gets going though, I’m thoroughly immersed. The objective in Dactyl Nightmare is to hunt down and shoot the other player in a small arena consisting of five floating platforms. But in addition to avoiding the other player’s shots, you have to look out for a pterodactyl that circles overhead and occasionally swoops down to lift unsuspecting players into the air.

Things get off to a bad start as the computer player lands a hit and my character explodes into giblets. Then the pterodactyl dives in and drops my character from height, dismembering him into meaty chunks once again. Shooting is tricky, as the gun fires in an arc and you can only fire once every two seconds, so you have to position the controller carefully. But by this point I have the controls figured out, and I’ve completely forgotten about the world outside. I adjust my aim and fire — the computer player explodes in a satisfying shower of meat.

Nineties VR chic.

At around this point the immersion is broken a little as I realise that the cables have become wrapped around my legs — a familiar problem for owners of the HTC Vive. I’m dimly aware of Simon yelling to “turn around” to unentangle myself. Then my two and a half minutes are up, and it’s time to emerge back into the real world.

I’m impressed. My expectations of this ancient VR system were set low, but the tracking was spot on, and I was quickly drawn into the VR world. You can imagine how mind-melting the experience must have been back in 1991. At 20 fps, the frame rate is far below what you could expect on a modern VR system, but this was cutting edge back in the 1990s. The CPU runs at 30 MHz, and the GPU at 40 MHz — about the same as the original PlayStation. But the PS1 came out a good four years after the Virtuality 1000 series.

David Prowse (Darth Vader!) has a go on Simon’s Virtuality machine at Play Manchester 2014.

I’m itching to have another go, but a queue is already building. I spot a young chap literally bouncing up and down with excitement as he waits. His name is Sam, he’s 14 years old, and he’s never played on a VR machine before, although he’s seen videos of Virtuality machines on YouTube. “I think this is going to be awesome,” he says, grinning.

I speak to another couple after they finish a two-player game. Greg, 24, has only played on the Virtual Boy before, so this was his first true VR experience. “I thought it was pretty good,” he says. “Considering it’s so basic, I can’t imagine what Oculus Rift will be like.”

His partner Zoe, 21, goes one further. “I’ve had a go on Oculus Rift, but this is much better because you use your whole body.” This is an illusion of course — the machine just tracks the controller and helmet, not your whole body — but the Virtuality’s motion controller certainly gives it an advantage over Oculus Rift. (Until the Rift’s Touch Controllers are released later this year, at any rate.)

A CRT monitor shows what the player is seeing.

Simon agrees that the old Virtuality machines still hold up well against the VR systems of today. “The Virtuality tracking is far superior to anything VR for the home that’s upcoming. I can say this confidently as Oculus Rift developers have even agreed after trying my VR — and the fact that the tracking system in the Virtuality machines cost about £6000 [$12,199]!”

These machines were certainly top-end pieces of equipment back in their day. A stand-up Virtuality pod cost around £30,000 just to manufacture in the 1990s, and they sold for a lot more, with the games costing between £5000 ($10,166) and £10,000 ($20,333) — a sobering thought if you think the Oculus Rift is expensive. Because of this high price — and the fact that arcades had to pay for an attendant for each machine to help players put on and take off the headset — it cost up to around £4 ($8) per go in the early 1990s (Simon says he was lucky that his local arcade only charged £2 [$4]). This was a high entry price considering that other arcade games were just 50p ($1) a go at the time, and the cost contributed to the early demise of VR 1.0.

Simon Marston, Virtuality megafan.

I check back on Simon at the end of the day to see how things have gone. The booth has been constantly busy, but unfortunately the problems with the right-hand VR pod have persisted. “I had to reboot it about 20 times today,” he laments. Simon thinks he knows what the problem is — but the bad news is that he can’t fix it. The circuit board that controls the tracking is bent, probably where someone stood on it at some point in the past. The only option is to replace it, but it’s becoming increasingly hard to track down the parts for these rare machines. Simon knows of four non-functional 1000 series pods in the Canary Islands that he could use for spare parts, but importing them will be prohibitively expensive — not to mention the fact that he’s run out of room in his garage to store them.

It looks like time might be running out for these pioneering VR systems. But Simon is determined to maintain their legacy: “I will never give up on keeping them going!”

Comments

14 responses to “The Man Who Is Keeping 1990s Virtual Reality Machines Alive”

a true VR fan, so many fakers these days

I used one of these systems back in the day. It was in a mall, it was quiet and a friend of mine and I had just came out of a movie and saw them and the attendant sitting there bored. We played it like 4 times or so. We asked the guy what was running it and he popped the side off and showed us the Amiga running it. Was super cool.

That was a super buffed Amiga.

I always wondered what ran these? I figured it was a customised PC or something. But then I remembered it was 1992 or so and the best you had back then was what, a 386sx33? Maybe a 386DX40 or 2-66? or something? Struggling to remember my terminology from way back then lol.

Either way, I got to play Dactyl nightmare twice at Carindale shopping Center, I *think* we went to see Encino Man in 1992? (My god… I feel old now lol) they had it at the bottom of the stairs to the cinema, and from memory I think it was like, 5 or 6 bucks a go. Expensive as back then. But damn, what an experience. I remember that being the first time I was truly blown away since being a kid and playing Afterburner in the arcade (the moving cabinet blew me away all the way back then!)

I remember our first match ended in my defeat, and our second ended in a victory for me at least 🙂 But what a damn good time it was.

Note: I ended up feeling sick as hell after that second match, now I realise it was the motion + jittery framerate etc. But I don’t regret that a moment 🙂

Oh yeah, that Afterburner with the 360 degree rotating cabinet was amazing! I used to get harnessed in and pretty much do constant barrel rolls for the entire game.

That sort of setup combined with newschool VR should be a winner..

I’m hoping that VR might usher in a new era for arcades.

Yeah man. 12 years old, 1993 in Hurstville Westfields. They had one of the first “Intencity” arcades. We saw Mario Bros at the cinema I think, and then I got badly sea sick in the afterburner-like pod haha maybe it was the terrible movie that made me sick…

486’s were around since 89. DX2’s were around in 92

Not to be overly anal champ but the Amiga was (and still is) a PC.

At the same time it doesn’t surprise me because during the time of the Amiga, IBM and compatibles may have had gutsy CPUs but required expensive peripheral cards to have proper graphics and sound (until id’s Carmack showed he could make a 3D game with full stereo sound run on a toaster).

Amiga’s and consoles had the advantage because they were made for one purpose; to play games. Thus their hardware was specific for that purpose and optimised as such.

That rule can still apply today as consoles are a fixed platform thus can outrun PCs but publishers have long since decided that making games multi-ports from the get go and just paying to have the compiler settings and text changed at the last minute is all that is needed.

But I digress; the Amiga while technically a PC also had attributes that put it in the console category so it is more realistic to call it a hybrid.

Great article. I remember playing this with my brothers on Hindley st. Some dude set up a shop with 2 of those units.

There was also a dungeon crawler where you battled skeletons with an axe.

I never saw the Dungeon crawler, just Dactyl nightmare from memory, that sounds mad!

I went there a bit! The guy running it let me have extended game sessions and I loved it, though you’d come out of an extended session and the whoel world felt weird.

I also worked at Timezone Meridian in Hindley St and we had the Afterburner 360. I clocked up a lot of time on that as well. It was a real shame when these sorts of experiences disappeared.

I’ve got a DK2 now, and would love someone to port over the old games.

oh man – timezone meridian was the BEST!

I can’t even fathom how they made money given the size and scope of that place but I loved it! Was heartbroken when it closed.

*deleted*

Doing god’s work.

I remember trying one of these. I recognise the machine.

I think it was a different game though.

It’s a pity there’s so few working models remaining.

Perhaps the best we can manage longterm would be ports of the games themselves?

The hardware wouldn’t be the same, but I suspect we now have the hardware to pull it off in an approximate sense…