What does a perfect world look like, exactly? Is it a place where everyone agrees to get along because we’ve set aside our differences, or is it a place where the trauma that so often gives birth to those differences never existed at all?

There’s an argument to be made that our struggles are what make us who we are, and our abilities to survive them are often what gives us the ability to recognise our own resilience. In different ways, all of this week’s best new comics grapple with that idea.

Relay

Cultural globalisation is the concept that the proliferation of art, beliefs and values across ever-expanding communication channels has the potential to bring people from disparate cultures together over their common consumption of similar ideologies. In theory, cultural globalisation is one of the ways that we, as a world of people, could become closer and more unified because of our cultural likeness.

That said, Aftershock Comics’ Relay — from writer Zac Thompson and artists Andy Clarke, José Villarrubia and Donny Cates — is a story about cultural globalisation’s potential for destruction and erasure.

The Earth of Relay’s universe was forever changed with the arrival of the titular Relay, an enormous monolith that landed on the planet and began broadcasting a message encouraging the flattening of global culture in favour of a kind of singularity of the mind.

While the Relay doesn’t compel people to assimilate into a proper hive mind, it does encourage them to erase their differences, a worldview that comes to define how the Earth’s intergalactic colonisers approach their jobs.

Employees of the Relay, such as hero Jad Carter, are tasked not only with ousting people who question the Relay’s roles, but also to travel to other planets with sentient life and offer them a chance to either conform to the Relay’s direction or be obliterated.

Even as the worlds around him buck and strain under the pressure to be standardised by the Relay, Jad’s faith in the monolith and its vision of a unified future is resolute. But even more important than that, Jad believes in Hank Donaldson, the otherworldly creator of the Relay who people have been searching for for years.

The Earth where the bulk of Relay’s first issue is set is a world that doesn’t quite know that it’s become a dystopia. Clarke, Villarrubia and Cates render it as a place caught somewhere between The Fifth Element, Gattica and Blade Runner — a densely-packed wonderland of flying cars, glittering holograms, and carefully-placed bunches of vegetation scattered throughout to undercut the indifferent hardness of megacities.

Unlike most dystopian parallels about the folly of man, Relay won’t leave you cold so much as it will make you really think about its premise. It doesn’t go out of its way to call the Relay and its message outright evil, but it’s impossible not to listen to Jad’s impassioned defence of his life’s work and think to yourself, “Is this really what you want? Is it what any of us would?” (Zac Thompson and artists Andy Clarke, José Villarrubia, Donny Cates, Aftershock Comics)

She Could Fly

Everyone struggles with intrusive thoughts of unbelievable horror at some point in their lives. You’re standing on the train platform and think to yourself, “What if I jumped?” You’re holding a newborn baby and wonder, “What if I just dropped it?” You’re having a perfectly fine morning and suddenly, all you can think about is the idea that every single person you’ve ever loved was leading you on and that you’re actually a waste of space.

It’s normal. Welcome to being human.

Those are the sorts of thoughts that haunt Luna, the 15-year-old heroine of Dark Horse’s She Could Fly from writer Christopher Cantwell and artists Martín Morazzo and Miroslav Mrva.

Luna’s thoughts are, in part, borne out of her potentially undiagnosed OCD, but they’re also a part of her struggle to figure out what her place in the world is. Nothing really speaks to Luna in a meaningful way. Not anything she’s heard from her counsellor, her parents, or other kids at school.

Nothing — save for the mysterious flying woman who’s been sighted zooming through the sky all across the Chicagoland area.

More so than anyone or anything else, the flying woman gives Luna something to fixate on and believe in. Suddenly, she has hope that maybe she isn’t worthless, that maybe she, too, can fly.

There’s a whole shady governmental conspiracy plot interwoven into She Could Fly, but the comic really is about the existential adrift-ness that sets in when you’re a teenager and never really quite leaves you.

The framing in almost every single panel is askew in some way that convey the anxieties Luna’s feeling as she tries to interact with people. Morazzo and Mrva “shoot” her from above in those moments where she feels the weight of the world bearing down on her, and from below when she’s feeling awkward, lost and alone.

Her frightening visions of biting into cacti or running over someone with a car are visceral and frenetic, giving you a keen sense of the constant stress her unbidden thoughts cause. You can’t help but feel for her and hope that, someday, she gets her dream of meeting the flying woman so that, at least for a moment, she can just breathe. (Christopher Cantwell, Martín Morazzo and Miroslav Mrva, Dark Horse Comics)

Farmhand

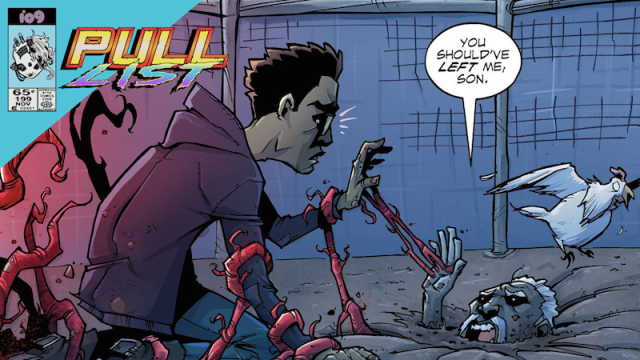

Image’s Farmhand, from writer/artist Rob Guillory and illustrator Taylor Wells, is a weird comic about the son of a black, Southern farmer who became one of the wealthiest men in the world after discovering how to grow plant-based human appendages that can be successfully grafted onto people. But, really, it’s so much more than that.

Zeke Jenkins, Farmhand’s hero, left the farm and the family business long before his father’s success, and the book opens just as he’s embarking on his first trip with his young family back down to his hometown of Freetown, Louisiana.

For Zeke, going back to Freetown isn’t just going home, it’s doing the work to bring together different parts of his family tree and, in doing so, reconnecting to the history that made his existence possible.

Freetown (which is a real place) is a settlement that was founded in 1872 by a group of former slaves and free people of colour who were able to buy a portion of the land that was once part of the Landry-Pedesclaux sugar plantation. (It should be noted that there are a number of towns founded by black people in the years after the Civil War who similarly named their settlements Freetown.)

Together, these communities were able to successfully cultivate the land and their own livelihoods at a time when the South was an even more perilous place for black people to simply exist.

Freehand envisions a scenario in which a black family, after decades of tireless work and struggle in a system that was designed to see it fail, was finally able to generate the kind of generational wealth that has always defined the American dream.

But that success comes at a terrible cost that Guillory brilliantly crafts out of multigenerational black trauma and modern bioengineering. The blood seeping out of the Earth on the Jenkins farm isn’t just the byproduct of the crops growing there, it’s also a reminder of the suffering, terror and death that came hand in hand with being a black entrepreneur trying to survive in the post-Civil War South.

Even though that sounds like a lot (because it is), take solace in the fact that as heavy as it is, Farmhand also manages to be funny as all get-out. (Rob Guillory, Taylor Wells, Image Comics)

Comments