Ann Nocenti wrote some of the most inventive, daring and pointed superhero comics of the 1980s. We’re all really lucky that she makes a triumphant return to the medium this week, with The Seeds #1.

It isn’t an exaggeration to say Nocenti was one of the most important comics creators of the 1980s. During her tenure as writer and editor at Marvel, she wrote an incendiary run on Daredevil, co-created classic characters such as Longshot, and sharpened the Chris Claremont era of Uncanny X-Men. At various turns at DC, she wrote numerous Batman stories, an entire run of Kid Eternity at Vertigo, and a Klarion miniseries.

When her comics career waned, a lifelong passion for journalism led her to editing at High Times and Prison Life magazines, as well co-directing a documentary film called The Baluch. Nocenti has never been too far away from comics, though, and has done smaller stints at Marvel and DC over the last two decades.

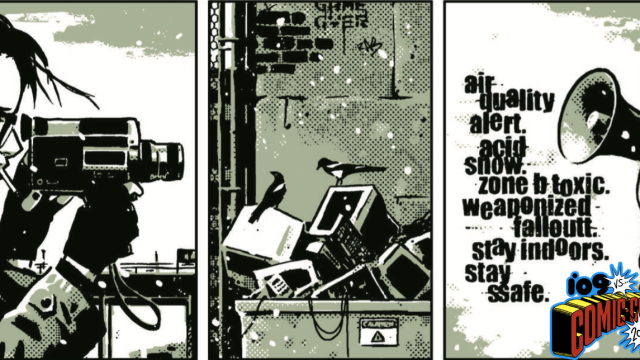

Part of the hotly-anticipated Berger Books imprint headed by Vertigo founder and hall-of-fame editor Karen Berger at Dark Horse and drawn by David Aja, The Seeds marks Nocenti’s return to regular comics-making. I spoke to Nocenti at this year’s San Diego Comic-Con about what’s changed in the medium and why she keeps coming back.

You’ve been in and around comics for so long and the craft of the medium has changed. How did you come to grips with the tools changing — things like captions and other storytelling mechanics — from the last time you worked on a regular basis?

Ann Nocenti: That’s a really interesting question, because I miss thought balloons. Thought balloons are considered corny now and artists don’t want to draw them. At some point, people started saying, “comics are literature,” “here’s the graphic novel,” [and] “it’s an art form.” For some reason, thoughts moved into captions, and I feel like there’s a delicate difference between a thought and a thought-caption.

Because, when you’re putting someone’s thought process in captions, you’re doing, almost, their higher voice. Their bird’s-eye view voice. Whereas a thought can be really dumb. A thought can be, “Shit. I gotta pee!” And I don’t want to put, “Shit. I gotta pee!” in a caption, because captions are supposed to have this, you know, seriousness to them. Lofty, whatever.

But some changes I’m glad about. It used to be, back in the day, you’d have to put an “Elsewhere…” and “Across town…” But now the readers are getting sophisticated enough to see the image in the panel has changed, the scene has changed. So, I’m glad we don’t have that any more, except once in a while, I’ll be reading a comic and not notice!

I talked to David and Karen before we started working on [The Seeds] and said, “Could we bring back the thought balloon? And maybe even redesign it so it’s a little more elegant?” And they were both like, “Nah.” So, next time I do a comic, I’m just going to keep asking artists if they’ll redesign the thought balloon with me, so I can separate high thoughts from “I gotta pee.”

I miss caption boxes because that used to be the place where the writer’s voice lived. Now it’s the character’s voice. As a writer, you’re servicing the character, and if you write or think or speak differently, there’s no place for you in there.

Nocenti: I mean, you can still put the omnipotent narrator in. The interesting thing in The Seeds is that I’m obviously inspired by [Akira Kurosawa’s film] Rashomon. Actually, the guy who wrote it died yesterday. I was really sad. Because Rashomon was the first time something that I had noticed in life — that everyone sees reality differently — was articulated.

You know, the quantum mechanics people talk about how as soon as you look at something, it changes. And cops talk about how every witness will describe the [same] person differently. So, I wanted The Seeds to have multiple points of view.

The reason we opened with the bees was because, on some level, this is nature’s point-of-view. You keep seeing animals looking at humans and bees are up to something. We as humans are stomping around on a planet to the point where nature is starting to notice. Nature is also collectively saying, “Wait a minute, should we do something about this?”

So, it’s Astra’s point of view as a journalist, but it’s also nature’s point of view. It’s the animals’ point of view. So, I wanted that feeling where, in the old days, you would have written omnipotent nature point-of-view captions

The general conceit of the series is that the world is on the brink of ecological collapse. The main character, Astra, is a journalist who’s kind of on the lower rungs of the practice, working for a paper that mainly puts out poorly-sourced fake news stories. But she wants something real, something to make her name. Where did the core ideas of the series come from?

Nocenti: Well, there’s sort of a back story. I’m technically the writer, David is technically the artist, but the process we’re using is sometimes I’ll send him lots of images and sometimes he’ll send me words, and we trade back-and-forth. We form some kind of “one storyteller” gestalt and it’s all done through email. It’s mysterious sometimes.

Very early on, he sent me a drawing he’d done of a dead man floating in a space capsule. And he didn’t even send it with any comment. I was like, “Wow, this is cool. This has to be in the comic, somehow.” So it’s a really mysterious process. That dead man in the space capsule then became a character and it comes up in the next issue.

Originally, we were doing a version happening at a 1950s tabloid. I was outlining the fourth issue. David designed this absolutely beautiful comic; it was kind of a black and white with touches and red, like an old newsstand Enquirer or Weekly World News. We had a journalist who was chasing things down like Bat Boy and Two-Headed Man, and we were making a statement about Fake News, but this was when Obama was president.

It got further and further and further, and then we were working on it when Trump got elected and the whole “fake news” thing blew up, and I sank into a depression.

I was like, “This is bad,” and also, “Our comic, we can’t do this comic. We can’t do this comic any more, because it looks like we’re making some weird joke about ‘50s tabloid journalism and equating it with fake news.” So we tossed the comic. I got really depressed.

One day, David and I just started emailing each other, and I was like, “You know, but… I still kind of like a journalist and I still like this alien-human love story,” because that aspect was always going to be about “the other”. Like, love the other. Love the person that doesn’t look like you, act like you…

So, I threw everything away, boiled it down to this much simpler thing, and then we decided, “OK, that’s a story we can tell.” Astra became a different kind of journalist and I gave the fake-news role to the character of Gabrielle. We started calling her a random news generator, somebody who kind of watches the odds like you watch a stock market and decides what the news is going to be.

The story and time stetting just kept shifting. David said, “Let’s set it in the shadows of the World Trade Center towers.” Those towers fell while I lived there. I’m strangely, technically, a 9/11 survivor. And I was like, “Fine.” I live in the shadows of the tower, that would be cool. There’s an impending doom.

But then again, Trump happened, and it wasn’t impending doom any more… it was doom is here. So then, David said, “How about we set it a tiny bit into the future?” And then that’s when we settled on this thing that still reflected our original idea of 1950s noir, but so close into the future it could be present.

We’re in a moment right now where it feels like every aspect of pop culture — video games, comic books, whatnot — gets pulled into a never-ending culture war. Your politics have always been in your work, especially during an era that some people are calling apolitical.

You wrote Daredevil comics where he worked pro bono for people who needed to fight against their landlords and corporations, et cetera. You wrote a Batman comic where Poison Ivy went after a Donald Trump analogue, and you talked about corporate raiders and the “greed is good” mentality. How do you feel about this culture war getting so volatile?

Nocenti: Well, my parents raised all of us to have a strong social justice bent, to do your civic duty, to be a civil servant. It’s kind of in our bones; all three of us have it. My brother is a lawyer, my sister is a surgeon. And then I became a comic book writer, which is not exactly the same. You’re not helping the world the way my brother or sister is. But I still had that in my blood.

Also, I was obsessed with film, especially documentary film. I loved Medium Cool. I loved Haskell Wexler’s film where it was fiction, and then it went into the Democratic National Convention of ‘68, and then he let the film become a documentary.

I lived in Hell’s Kitchen and I would see a Legal Aid clinic when I walked around. I said, “That’s where Daredevil should work.” Kids were skateboarding around, there was graffiti, you know, there was some crazy fly shit happening in Hell’s Kitchen in the ‘80s when I was there.

So, I would take pieces like a documentary filmmaker — which I would later become — I would take pieces of reality, put it in the comic, and try to weave it into the story.

With Daredevil, it’s a beautiful setup because he has the vigilante street thing but he also has the courtroom. So, by his nature there has to be something for a lawyer to wrestle with. Most characters you don’t have to worry about that, but with him, the social justice angle is natural because of his work.

Now, I think I bury it deeper. Back then, I always tried to show both sides. I never would say, “Here’s these eco-terrorists and they’re dumping oil to stop a corporation from dumping oil in a river.” I always tried to show both sides, and now I’m letting it seep in a really different kind of way. It’s all subtext.

Like, there’s an animal rights angle coming up in the next issue [of The Seeds]. I did an animal rights story in Daredevil 30 years ago that was too heavy-handed, in my mind. I go back and read those comics and go like, “You know, you should have kicked some sand over those ideas, Annie.” Now I’m still trying to kick more sand over it, but they’re still things that obsess me.

When I was a kid, I used to sometimes feel funny eating meat… you know, cute animals. I’ve never stopped eating meat, but I’ve also never stopped feeling weird about it. In Seeds, I don’t give that conflict to a journalist, I give it to a farmer. So, I guess I’m finding other ways to tell the same story. From other angles.

Let’s take it all the way back to the most basic question: Why come back to comics?

Nocenti: It’s odd. I’m hooked. I love them. You know why? Because it’s so hard to do a perfect comic. I can do a piece of journalism — you’re a journalist, you’ve done comics — a piece of journalism, you can get it pretty close to what you want. You can write an essay, get it pretty close to what you want. I’ve written film, I’ve had a film of mine made and I hated how it ended up, because it goes out of your hands completely.

I like collaboration and in the collaborative medium of comics, it is so hard to get that perfect linguistic balance between image and word, and I keep trying. And so, when David sent me an email one day, asking, “What are you working on?” I said, “I’m going to drop everything if you want to work with me.”

We did a Daredevil story together and it was like this little kind of gem of story. I have a bunch of little stories that I think might be a good comic book story. You know? I did a story with David Mazzucchelli, an Angel story, and I thought, “Maybe that’s a good one…”

Man, I remember that story from Marvel Fanfare! It really was a perfect little gem.

Nocenti: You know, you write all this stuff, and you write arcs and you’re under pressure and you have to write something overnight, and you just can’t do it. You cannot do it. When you’re on deadline, you want to do one a month, and the artist sends you 10 pages and the editor says, “Write them tonight!” If you’re going to write 10 pages, that night, even though you had a script, you have to rewrite everything to fit and balance. It’s not enough time.

Karen Berger gave us a long lead time so we could really take our time with the first issue. And I think it makes a world of difference, because you can write a page, go to sleep, you dream, your unconscious does some work, you look at it again, you strip out unnecessary words, you move things around. David is a genius, he’s doing things in the comic I didn’t even notice.

There’s a scene with a farmer in the next issue, and halfway through, the farmer has to slaughter one of his pigs, but he loves the pig. Because it’s given him lots of piglets. It’s sustained him.

And there’s this moment — David just had the farmer take his ball cap and turn it around to face front. It was backwards, but when he had to go do the job and kill the pig, he took the ball cap and turned it around face front.

That’s like… that’s not in the script… and he does all these little things that are just like, “Oh, man…” You know?

Comments