The score was 4 to 3, two outs in the ninth, when I woke up on the couch. No one was on base. “I don’t need to see this,” I said. “Nah, stick around,” Dad said. I had two games that day, the World Series on TV, and Hardball! on my Commodore 64. If the Los Angeles Dodgers didn’t win one, I’d make them win the other.

Over the summer of 1988, before my older brother went back to school, he showed me how to edit rosters in the baseball video game, albeit crudely. 20-five years ago, there was no EA Sports, no MLB The Show, no zillion-dollar deals putting big name star on the cover of a game. There was only a bleep-bloop world and a lot of imagination propping it all up. But by loading the code of Hardball! into our homebrew word processor by accident, my brother found that we could manipulate the text. First we put our own names into it. Then our friends. Then I sat down with box scores from the agate page and started penciling in names of real-life players.

It wasn’t as simple as that sounds. For starters, any new name in the lineup had to be the same length or shorter, in characters, as one it replaced. Then, every character in the combined roster had a decimal value — 65 for A, 90 for Z, for example. Whatever changes you made, the new total had to equal the value of the original. You could steal from and add back numbers to the total by fudging with other names, but if you just wrote in a guy’s name without doing the maths, the batting order would look like a mess.

There was a lot of trial and error, saving and loading, and sometimes abbreviations and out-of-place upper- or-lowercase letters were necessary to force the illusion. Heading into the events of Oct. 15, 1988, there was one name I couldn’t seem to get into the game with his teammates: GIBSON.

20-five years later, sports fans know the story I’m now getting at. Tommy Lasorda also couldn’t get GIBSON into his starting lineup for the World Series, and it wasn’t because the name has a decimal value of 450, putting you over the limit on a roster where STUBBS, SAX, GRIFFIN, and HAMILTON didn’t add up to Garvey, Lopes, Russell and Cey, either.

Even injured, Kirk Gibson was utterly essential to any meaningful game, televised or on a computer, in October 1988. At the beginning of the World Series, Gibson possessed, in the words of Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times, “the most devastating .154 average in the history of playoffs.” Facing a 3-1 deficit in the National League Championship Series, Gibson swatted a 12th-inning home run to even matters at two games each. The next day, he pounded a three-run bomb before twisting his right knee trying to break up a double play. He was injected with painkillers repeatedly to keep playing, as the smoke-and-mirrors Dodgers emasculated a powerful New York Mets club at the zenith of a short-lived and frustrated dynasty. After heaving themselves over the N.L. finish line, Gibson and the Dodgers faced the Oakland Athletics in a World Series they would be hard pressed to win even with him at full strength. As it was, he could barely walk.

The evening of Game One, a Saturday, I scrawled out letters and numbers and added up combinations on pin-fed printer paper before being called to dinner and giving up. My brother was away and no help. Asking Dad was liable to raise some uncomfortable question about my homework. Anyway, he’d heard me blather enough about video game baseball, and how I replicated José Canseco’s 40-40 season by switching a hitter between third and first in the batting order game-to-game. “Great, but it’s not real baseball,” he said. It stung. I still hear those words whenever I get too proud of my digital feats in today’s more sophisticated games.

Real baseball was at 8 p.m. on NBC that night, and the Dodgers, our sentimental favourites, were sure to be murdered in it. L.A. was a team of terrible hitters to begin with — that starting infield I mentioned accounted for 20 home runs all season. Sure, they were facing a lineup of bogeymen like Canseco and Mark McGwire and Dave Henderson. The Oakland Athletics also featured lesser menaces like Tony Phillips and Carney Lansford, who held the bat like he was strangling a cat, somehow managing to get on base all the time. On the mound, the A’s had a staff of Dave Stewart, Bob Welch and Storm Davis, backed up by Dennis Eckersley, a future Hall of Famer who along with manager Tony LaRussa would create today’s showcase role of the closing pitcher.

In the preceding American League Championship Series, Oakland demolished a Boston side that was even better as a team in every meaningful hitting category. In the ALCS I remember Canseco blasting a seventh-inning missile to tie the score at two, still rising as it cleared the wall. Mike Greenwell, the Red Sox left fielder, did not move a muscle below his neck on the play; he simply stared up and watched the ball enter orbit. I wasn’t in the mood to see any more of that.

“As soon as this gets out of hand, I’m done,” I told Dad. I had a baseball world waiting on the computer, one where I was in charge — as long as I could get the names right.

A quarter-century later we can rewrite history at will and with far greater ease. Titles like FIFA and Madden NFL update throughout the year with challenge scenarios based on outcomes from significant games during the season. NBA 2K and MLB The Show have season modes that serve players the lineups of games being contested that day, with commentary that remarks on events of the real world .

An M.I.T. study of sports gamers in 2011 showed more than 80 per cent go to their consoles to replay real-world events. And indeed after the spine-tingling final day of the 2012 English Premier League season, which saw Manchester City score two goals in stoppage time to capture its first championship in a generation, more than five million players bombed the EA Sports servers to attempt to recreate the feat in their living rooms in FIFA 12.

That was a far cry from the fantasy offered 25 years ago, when simply getting an accurate lineup into a video game was about as easy to write as the storybook finish to a real game. But figuring out those lines of code was a safer bet for me on Oct. 15, 1988, when the Dodgers trailed the A’s 4-3 with one out left in the ninth, than Los Angeles getting two runs to win on some miracle swing.

“I don’t need to see this,” I said, as pinch-hitter Mike Davis strode to the plate, more likely representing the final out and not the tying run.

“Nah, stick around,” Dad said. “Let’s see what happens.”

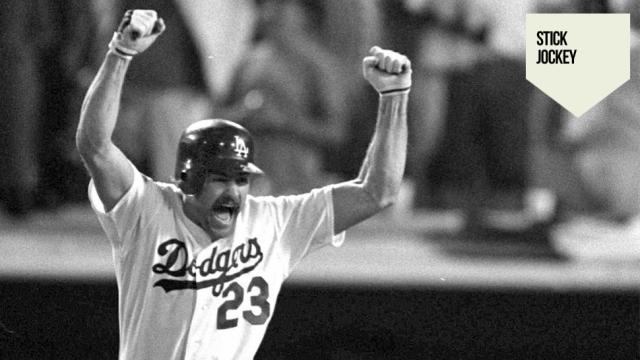

Davis worked a walk and I sat up. Up came Gibson, for an at-bat that today can’t suffer many more sentimental recountings, much less my own. Just from the context you should know what happens next.

“That’s a home run,” my brother said to his friends, two hours down the road in his dorm. Dad and I both leaped from the couches. We landed with the ball, 2,500 miles away in the right field bleachers. I’ve had 25 years to think of that moment, and I still can’t put the happiness into words.

In the aftermath, after Dad calmed down Mum and assured her the house was not on fire, and we all went to bed, I went back to my computer. I typed LOAD “*”,8,1 — determined to bring Gibson back for an encore. I had to juggle the lineup, but he was there, batting ninth. Kirk Gibson could hit home runs all day. The real miracle was getting him into the game.

STICK JOCKEY

Stick Jockey is Kotaku’s column on sports video games.

Image by Associated Press

Comments

One response to “Remembering A Miracle In The Early Days Of Sports Video Games”

What a fantastic story. Amazing how it all tied together. Thank you for that!

It brings back my own memories of tweaking with roster names and lineups in the early days of sports gaming.

If only all the writers on Kotaku were like this…