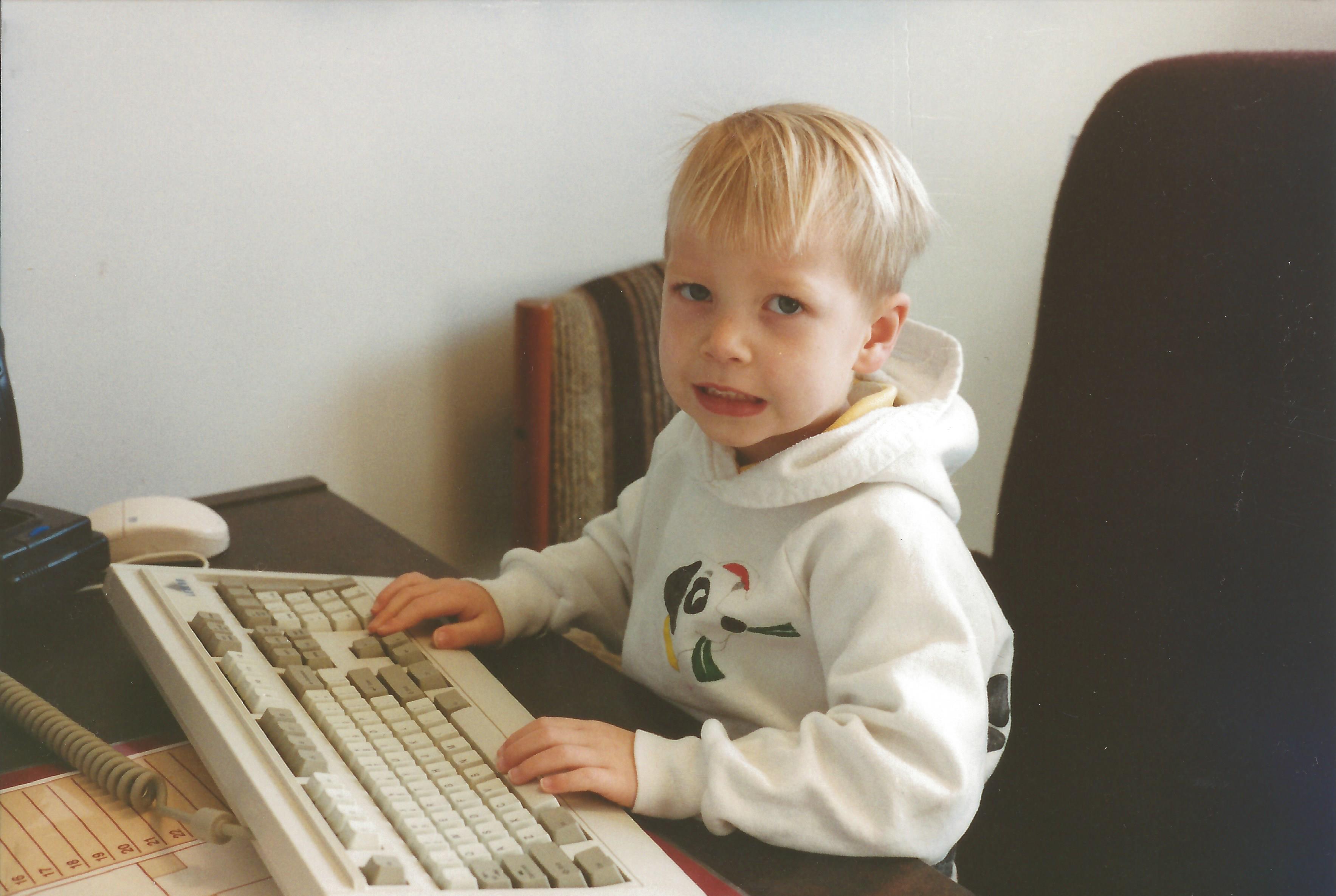

When one of World of Warcraft’s top 10 guilds recruited Cam as their chief hunter, his suicidal thoughts surged.

To earn the enviable invitation, Cam had spent 16 hours a day grinding on WoW, to the detriment of everything else. He told his father he’d scored a job at a local restaurant, but every day after his dad dropped him off at the McDonald’s across the street, Cam would hop the first bus home and log back on.

There was no job. There would be no paycheck. Cam’s only obligation was to his night elf hunter, and it was an all-consuming commitment.

What if I just ended it? Shortly after transferring WoW servers, Cam wrote a final note to his parents. On a phone call with Kotaku, Cam recalled how his mother had made Swiss chard soup that night. Upstairs, sobbing over a warm bowl, he strategised a suicide plan.

Mid-thought, his phone buzzed: Cam’s only friend invited him to see the movie Superbad. Fuck it. In his buddy’s car before the movie, they smoked enough weed to cloud the windows grey with smoke. Superbad was hilarious. Wave after wave of laughter came over Cam.

After the movie, he realised that he was a danger to himself.

Today, Cam has been sober from gaming for seven and a half years. For him, it was a problem that insinuated itself into every corner of his life over the course of his adolescence.

“Gaming fulfils all of my needs in one thing,” Cam explained.

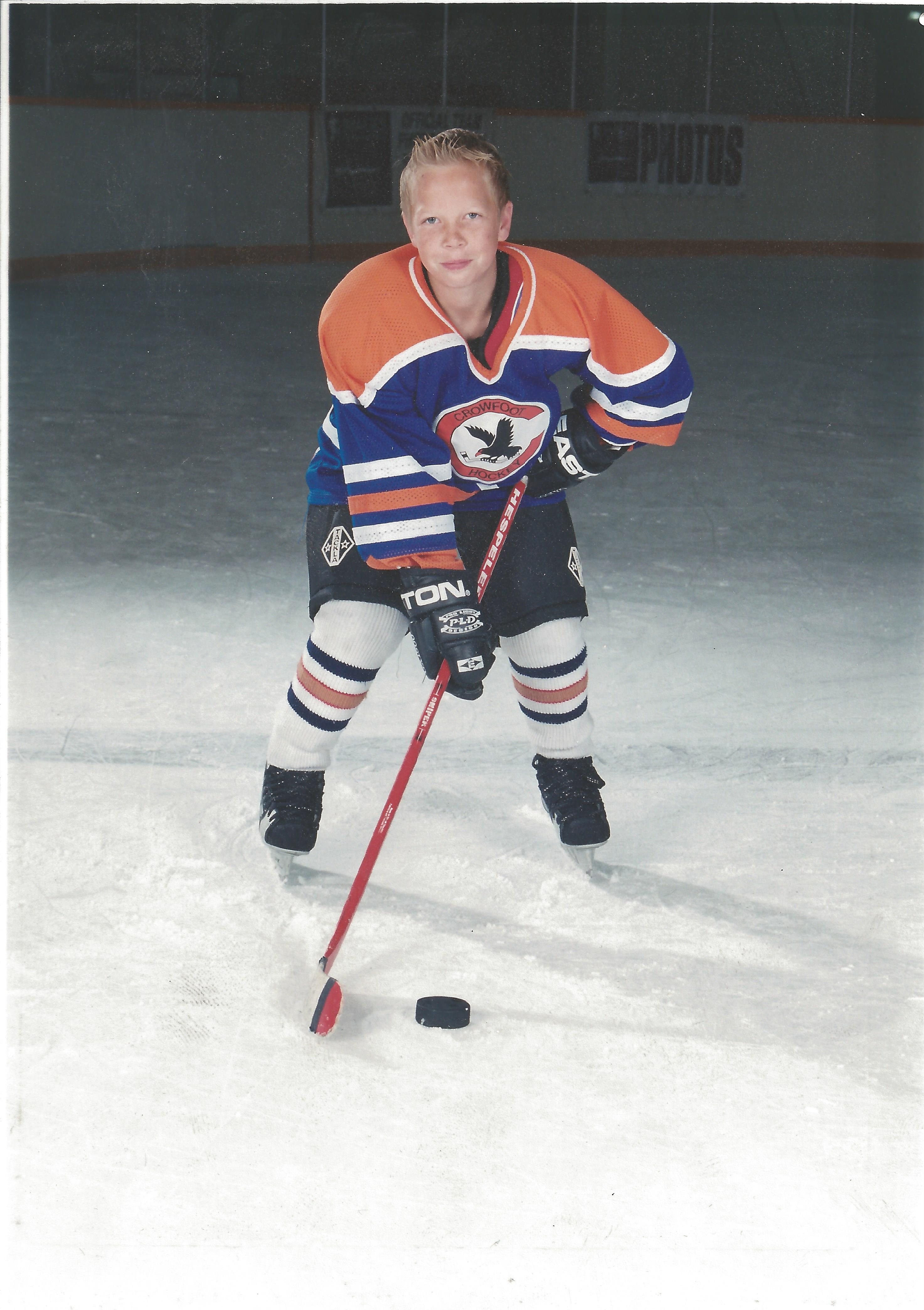

He earned rewards consistently. Benchmarks for success were clear, tangible. He got his social interaction. Structure. It helped him forget about how he had dropped out of high school, lost friends, got too out of shape for hockey. Or his bullies, his deteriorating family life, his pretend jobs. He had an identity.

Unambiguously to him, the word “addiction” explains his relationship to games: Obsession, withdrawal, compulsion, lying, a total shift of values.

It’s clear that some minority of game players, such as Cam, have found themselves gaming so compulsively that they neglect the rest of their lives — and can’t get themselves to stop. But what they, and experts, disagree on is whether or not that constitutes an “addiction” to games, whether games are “addictive”, and whether the excessive gaming is just a symptom of a deeper issue.

The addition of “gaming disorder” to the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases this year has spurred contentious debate on all sides of the issue.

Until recently, it was controversial to apply the word “addiction” to a behaviour. Addiction was a term reserved for heroin, crack, cocaine — tangible things the body screamed out for. Substance addiction makes sense; behavioural addictions, psychologists argued, were fuzzier.

Nicotine is addictive at its core: Smoke too much, and you’ll risk craving cigarettes, feeling volatile without a smoke, struggling to stop, even while knowing the health repercussions.

But when the vast majority of players can enjoy Fortnite long-term without suffering a major blow to their quality of life, is “gaming addiction” a legitimate problem?

In the 1980s, poker fiends in chronic debt — whose lives suffered because they couldn’t stop — became diagnosable. They had a gambling compulsion, an impulse-control issue.

It wasn’t until 2013 that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders reclassified gambling addiction as “gambling disorder” in its new behavioural addictions category. It was the first non-substance-based addiction disorder officially recognised by the DSM.

“Research to date shows that pathological gamblers and drug addicts share many of the same genetic predispositions for impulsivity and reward seeking,” wrote Scientific American magazine shortly afterwards.

“Just as substance addicts require increasingly strong hits to get high, compulsive gamblers pursue ever riskier ventures. Likewise, both drug addicts and problem gamblers endure symptoms of withdrawal when separated from the chemical or thrill they desire.”

The recognition of gambling disorder paved the way for the World Health Organisation’s contentious new “gaming disorder”. Announced late last year and confirmed last month, the classification of gaming disorder instantly piqued the interest of overbearing parents whose children’s after-school Fortnite hobby often wins out over homework.

Among a lot of gamers, it’s piqued the ire of enthusiasts who say their hobby is already stigmatised enough. While “gaming disorder” might be a real problem for a small subset of gamers and therefore worthy of recognition, nobody wants their parents sending them to a psychiatrist just because they put 100 hours into Xenoblade Chronicles 2, either.

Gaming disorder is flypaper for ideologues on all sides of the conversation. It doesn’t help that the definition has been vague.

At one point, researchers diagnosed gaming disorder using 18 different methods, producing prevalence rates between zero per cent and 45 per cent. Now, according to the WHO, gaming disorder is “characterised by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other interests and daily activities, and continuation or escalation of gaming despite the occurrence of negative consequences”.

The WHO adds that, to fit the bill, a gamer’s habits have to impact their social, educational and occupational lives for about a year. In practice, that can look like a lot of things. And since most AAA games these days are designed to be seductive time-sinks, gamers, non-gamers and psychologists alike are debating whether gaming disorder is even worth recognising.

Experts on the psychology of gaming have themselves warned of a “moral panic” around gaming addiction, in one paper arguing that it “continues to risk pathologizing normal behaviors”, adding, “video game addiction might be a real thing, but it is not the epidemic that some have made it out to be.” (A recent metaanalysis including 19,000 subjects concluded that less than only about three per cent of game-players are at risk.)

Gaming disorder’s medical approval has fed valuable fodder to the parental thinkpiece economy. A cursory Google search dredges up dozens upon dozens of worried parents’ published missives in The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, The Guardian or Mashable.

Kids who play more than a couple of hours of Fortnite, the hottest game du jour, are squirming under new parental scrutiny. Does 20 hours of gaming a week constitute an addiction, as the BBC seemed to claim, or at least heavily imply, last month?

What recovered gaming addicts interviewed by Kotaku say is that addiction is defined much differently than the sheer number of hours you put into a hobby.

It means everything else is eclipsed by the need to 100 per cent a level. It means not being able to hit “log off”, even though tomorrow is your son’s graduation. It means not much else feels good.

Cutting through the ideologies and fears around gaming disorder are real people whose stories about compulsively gaming weigh against the papers, blogs, forum posts and manual entries. What about the people who fit the WHO’s bill?

Benjamin*, who’s been sober from games for three years, told me, “Maybe if I wasn’t exposed to games, I would have become a drug addict.”

As a teen hiding out in his room, he couldn’t get himself to stop gaming before 3AM, sometimes slipping until 5AM, when he’d hear his mother get up for work. Then, he’d rush into bed and pretend to sleep.

Benjamin couldn’t stop playing — not when he failed out of university three times, not when he lost his spot on the wrestling team he’d dreamed of being on.

One day, when he was still at school, he asked a frat brother to lock away his gaming mouse until midterms were over. He’d been gaming for several days straight and thought cutting himself off might help him focus.

Days later, Benjamin “picked him up by the scruff of his shirt and threw him against a wall” to get his mouse back.

When I asked whether Benjamin blamed games for his gaming addiction, he offered a stern “No.” He played every type of game he could get his hands on except sports and puzzle games, so it wasn’t a particular mechanic that hooked him, he said.

“Pretty much any way of getting the fuck out of life — that’s what I wanted,” he told me. “I wanted to be anyone but me. I wanted to be anywhere but here. I wanted it to be any time but now.”

Benjamin added that he often overindulged in drinking and pornography, too. And, after spending some time in therapy, he’s finally addressed some of what made him feel the need to “get the fuck out”: Family issues, anxiety, depression.

Most recovered gaming addicts Kotaku interviewed attested that video games were far from the root of their problems.

“I think excessive gaming is almost always a symptom of an underlying condition,” said Harold*, who was addicted to World of Warcraft and attended several clinics for treatment. For him, and three other sources, that underlying condition was depression.

Several other sources interviewed had suffered from other addictions prior to gaming. Scott J. was, in his words, an “out of control” drinker until he was 23, when he joined an Alcoholics Anonymous fellowship. Soon after, he told me, “I started playing a lot of video games, having never heard of video game addiction.”

Scott is loath to mention what games he compulsively played, arguing that the nature of the activity doesn’t matter when he’s talking about the bigger issue of a general addiction disorder.

“It’s perfectly clear to me that I have one condition that involves all these things: Obsessive compulsive, denial, hiding, lying about it, the fears, the crazy thinking, the irritability if I’m staying away, the mental cravings and urges, the distorted thinking,” he said.

“In my 20s, I tried to numb it out with drinking. In my 30s, I numbed out with gaming. The idea that they’re two different conditions doesn’t make any sense. It doesn’t match my experience at all.”

Curiously, a lot of sources who believe their gaming addiction stems from mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety were unhappy about the WHO’s “gaming disorder” classification. Why should a therapist focus on gaming obsessively when that can be a symptom of something deeper? Or another way to “numb out” of life, in Scott’s words?

Sure, staying away from games helped gaming addicts glean some perspective on their habits and where their compulsions came from — but quitting games wasn’t the be-all, end-all solution to pushing “reset” on an addict’s life, sources say.

Hartmut*, who went “cold turkey” after spending all his time trying to hit the Diamond rank in Overwatch, says his initial optimism about “gaming disorder” has turned into fear.

“I’ve actually come to think about the WHO draft as being dangerous,” he told me over email. “If gaming disorder was officially recognised, people would get diagnosed for a mainly behavioural issue, which in turn most likely originated in an underlying, deeper mental health issue (like, in my case, depression). Those ‘root’ issues could easily be overlooked.”

Although recovered addicts agreed that addressing root causes for gaming addiction is key, Dr Douglas Gentile, psychologist and Iowa State University’s Media Research Lab head, has another perspective. In 1999, Dr Gentile began researching gaming addiction “largely trying to show that it was wrong,” he told me for a 2015 article on the topic. Instead, he was converted.

Over the phone last year, he told me that, after surveying thousands of subjects, “We found that gaming precedes the depression if they’re damming enough areas of their life where it counts as a disorder.”

He describes it as a chicken-or-egg scenario: Sure, a lot of problematic gamers are diagnosed with other conditions. If a person spends too much time cooped up on their own with any activity, it could stunt their social skills so, when they do go out in public, they’re anxious as hell. It can mean being so isolated, gamers lose the ability to cope with life. That can help spur its own problems.

It’s difficult to find lifelong gamers — people who operated under the gamer identity for decades — who attribute the root cause of their troubles to video games. Four sources adamantly stated they love games — they just can’t play them any more.

A few, however, noted that their games of choice hinged on gambling-like mechanics: Loot boxes and the like.

Hartmut, who was seeing a therapist to help with his depression, would roll over in bed to grind on any of the free-to-play games installed on his phone — Clash Royale, Hearthstone, Fire Emblem Heroes — “each of them psychologically made so that you have a progression loop, get dopamine boosts by getting a super rare and shiny item, and get daily rewards so you check in more often,” he said.

“In most cases, understandably, they are also designed so that later ‘expansions’ gradually introduce stronger cards/characters/gear/skins to the game, maybe even just for a limited time – just to get you into buying stuff,” he continued.

“Had I not uninstalled Fire Emblem Heroes (my favourite franchise of all time, has me emotionally attached because of nostalgia), I would be a poor man now.”

Over the last year, there’s been a muscular, widespread pushback against loot boxes, even from legislators, citing their gambling-like properties.

Compulsively playing, say, first-person shooter Call of Duty is a little different from getting hooked onto Clash Royale’s dopamine loop. Yet, scrolling through stories on gaming sites (yes, like Kotaku) and subreddits and forums, there’s immense scepticism in the gaming community around gaming disorder, and even a certain strain of defensiveness.

Cam, who now runs GameQuitters, the largest online support group for video game addiction, told me that’s probably because of a lasting stigma from the violent-games moral panic of the 1990s, when parents and governments were concerned that playing GoldenEye would turn kids into killers.

“Whenever there’s a conversation around gaming there’s a natural defensiveness that’s extremely high,” Cam told me.

Some people don’t like hearing the idea that others might want to stop gaming. Every couple of weeks, Cam receives hate mail, harassment or death threats because he runs GameQuitters. Six months ago, someone told him he should walk off a pier with cement tied to his shoes.

Sometimes, he says, when the public conversation around gaming addiction resurfaces, the subreddit he moderates, /r/StopGaming, is raided by mobs of trolls.

“All the threads were people screaming at and harassing us. I can handle that. It doesn’t get to me. I understand it,” said Cam.

However, he said, it can impact people on /r/StopGaming whose entire lives and identities have been tied to gaming for as far back as they remember; it can further alienate them, make them feel guilty for seeking help.

“The 13 or 14-year-old in the Reddit community who feels vulnerable, just quit gaming, he’s feeling like he’s no longer part of his community and all these people come and say they’re embarrassing and their addiction is not real — people read that and feel ostracised,” he said.

The main upside to the official classification of gaming disorder is that it might help some people get their lives back in order. It can be a buoy for gamers who can’t figure out why their friends are OK putting down the PlayStation 4 controller after only two hours, while they have to keep going.

“I thought that to be an addict you needed to have a needle in your arm, be lying under a bridge, or be drinking from a paper bag,” said Benjamin. He eventually sought help for his addiction after moving back in with his parents. He’d been seeing therapists since he was seven, but none had ever diagnosed his gaming addiction. He’d never heard of that himself.

One source, Jacob, said that when he sought help for his gaming addiction, a professional addictions counsellor told him that the real issue was that he was forgoing social connection. Offline games were the issue, said the counsellor. He should game online. So Jacob binged on Starcraft 2. The problem got worse.

Without proper guidelines, professionals didn’t take him seriously. They might today.

Online, Benjamin and Jacob began attending text and voice meetings with other recovering gaming addicts. Now, they help lead Computer Gaming Addicts Anonymous, a grassroots 12-step group for gaming addicts.

“I’m just trying to let people who have a problem know they they can get help,” he said.

CGAA’s recovery program sets boundaries for hundreds of problematic gamers. Like Alcoholics Anonymous, its members teach gamers that games aren’t the sole problem; their mental health is.

However, abstinence is the only way for gaming addicts to uncover the roots of their self-destructive behaviour. It’s a philosophy widely shared among the recovered gaming addicts I interviewed.

Cam’s new hobby is surfing, which, he said with a laugh, he simply can’t do for 15 hours a day. Progress isn’t as measurable as in WoW. Rewards, like catching a good wave, aren’t consistent.

“Yesterday, when I went surfing, I caught a wave. I was fully immersed in that moment. I wasn’t able to focus on anything else,” he said.

But the crucial thing, he added, is that when he surfs, he always has to come back.

*Asterisks indicate names changed to protect anonymity. If depression is affecting you or someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

This story originally appeared in July 2018 and has been retimed to highlight the wonderful contributions women have made to Kotaku Australia over the years, our way of acknowledging International Women’s Day.

Comments

23 responses to “The Truth About ‘Video Game Addiction’”

Yeah the chicken and the egg issue with diagnoses is always problematic (FWIW sounds like they are experiencing distress intolerance more than anything else).

My concern is that a WHO definition for gaming disorder may actually increase the difficulty for mental mental health professionals attempting to diagnose patients in situations like this. A plethora of definable conditions doesn’t help anyone determine whether those conditions are causative or symptomatic, so additional conditions may just end up obfuscating the real problem (esp. re: addictions, where the atient’s knowledge of the incorrectness of the diagnoses can easily be mistaken for push-back against the diagnosis itself).

From what I remember reading back when the WHO first decided to classify the disorder was that in many, many countries, WHO acknowledgement of a condition is required before governments will acknowledge it/allocate funding to it/allow it to count towards existing programs etc.

I know this is serious business but I want to make a joke abut how Cannabis saved this guys life.

Is there’s anything marijuana can’t do to make life better?

If there is, I haven’t found it.

I think video game is just like every other addiction: People innately seek out altered states of mind. Sometimes to the detriment of the people around them. It’s why kids spin around in circles and then stair at the carpet, why dad has several beers after work, and why bogans lick toads. Beautiful in it’s way.

Great article – well balanced and considered.

Oops.

Didn’t have one when I was a teenager growing up.

Definitely do this more than I should as a 30 year old.

same

You shouldn’t need to hide from your mother as a 30 year old 😉

Smart ass.

No one becomes an alcoholic because they’re mentally healthy and happy. Alcoholism stems from coping with depression more often than not. Gaming for hours on end is an escapist behaviour because, once again, you’re coping with depression. It’s just a different kind of addiction. Gambling every day and winning makes you feel good AND rewards you monetarily, so you don’t think about how much you hate your life.

Honestly, I know myself and my behaviours and never began drinking because I knew what I would turn into. It’s all addictive personalities and depression coping behaviours.

(WHOs describer isn’t specific enough though.)

She didn’t. She started at 13 in a social setting, because it was fun and just something people do. I’d argue a lot of people share her story. Drinking is socially acceptable and often required to fit in, depending on where you find yourself.

https://inews.co.uk/news/health/height-drinking-i-found-i-crashed-car-i-sent-court-summons/

Sure, I think some people use gaming for escapism, but there’s a line between being able to choose to stop and being compelled not to. I think people who are suffering gaming addiction have passed over into the latter.

Got plenty of mates in the navy who are alcoholics, they were pretty well balanced no depression, they just succumb to the culture.

Before long they are drinking almost every weekend and although there time off

Good article…I immediately drew parallels with workaholics from my workplace…people who come in early, leave late, totally goal driven, and seem to avoid their homelife/outside of work life. Personally though, my gut feeling lies with the ‘I would have probably become addicted to something else’ school of thought for much of it, but it would be just as wrong to wholly ascribe to that as a blanket causation…

I game a lot, but I’m in my late fifties, kids are adults with their own lives, and my partner and I are settled in our lifestyle. I’m a desktop PC gamer though, and have it set up just the other side of a wall/doorway to my wife’s loungechair, so we aren’t isolating each other. The difficulty comes in with online multiplayer, where a gamer has to commit to ‘that’ environment, to the exclusion of the real world, as you can’t simply put it on hold while you deal with the other…lack of a pause capability places commitment burden on a player.

Can agree with avoiding home life, or lack there of In my case when I lived alone, I would work late rock up early do extra hours just because home was boring nothing to do.

Didn’t have a TV or internet for ages, so work was actually the only stimulating thing in my life and I kind of hated my job.

A core problem is related early in the article:

That’s a societal issue. We are fed and fucking SWALLOW this bullshit line that aspiration is enough – that if you work hard, you will get ahead… But that’s a fucking lie. Good, honest people work their fucking guts out their entire lives and never get anywhere out of it, while those born to it just fall into success because the way was prepared for them. And they have no interest in sharing.

It’s not enough to promise everyone a better chance at not being at the bottom of the pile, because that always leaves out the people who will make up the base of the new bottom of the pile. What we need to do is make the bottom a better place to be. And that’s so very much NOT our society’s focus – because why share the wealth concentrating at the top and make the bottom a better place to be, when you can just lie, tighten your grip on what you’ve got, and lie that everyone’s got a chance at not being on the bottom if they just go get it themselves?

And that leads to where we are: a rigged system where those at the bottom can’t win. Where hard work isn’t enough and doesn’t guarantee any kind of advancement or success.

…And then video games come and offer exactly that: clear, tangible, achievable benchmarks for success. Consistent reward. Rules that make fucking sense. A degree of fairness. What we SHOULD be getting out of real life… but aren’t. Is it any wonder escapism to that kind of system is so attractive? So addictive?

If hard work were enough to get ahead in real life, if the rules made more sense, if the rewards were consistent and reliable, we’d need less escapism.

Or you can work too hard, get called in to the MD’s office and told you’re a financial liability because the company owes you so much money in leave and banked RDO’s.

The system isn’t just rigged so that it’s almost impossible for many people to get out of the bottom or the gutter, it’s rigged so that these people die … slowly!

The epidemics we have in the world of autoimmune disease, frustratingly stubborn chronic obesity, cancer, gluten and lactose intolerance, etc., epidemics that we did not have in humanity 100 years ago — I hasten to add, prove to anyone who contemplates and does research that food-production and agricultural corporations, in cooperation with Food & Drug Administration in the US and similar organizations in the EU and Australia, etc., are systematically practicing slow genocide against the poor who cannot afford “organic” or similar food.

Hydrogenated vegetable oils were touted as “healthy cooking fat” for decades at the time when most people were using butter and ghee to cook. Raw, unpasteurized, unhomogenized milk is “illegal” to sell in many countries while pasteurized, homogenized milk is advertised as the only “safe” and healthy milk you can consume. Whole, multi-trillion dollar industries are built on nothing but ONE nightshade vegetable, like tomatoes or potatoes, and only in the last 3 years have some specialists managed to popularize the problem with lectins. Wholemeal grain is thought of as a health food by 99.9% of people today, while ancient cultures resisted it and spent decades perfecting the methods of eliminating the lectin-rich crust of the grains. These are just some examples but the rabbit hole is almost endless, and it leads to one conclusion: the slow elimination of the poor by feeding them disease-inciting food, sometimes while labeling it as “healthy”.

You are the one making the grand claims, the onus is on you to prove them.

Wow, cannot upvote this enough.

This was a really good article. I can relate to a lot of what is said here. I find myself being shunned for any type of video game by friends, partner, family, which has led me to play F2P games on my phone which has begun a new issue altogether. I definitely feel it’s more of an underlying issue or triggered by something else.

I can attest to the viewpoint that for those who involve themselves in games and believe it is an addiction, it is usually related to other factors which you generally do not have control over. People have mentioned depression, anxiety, familial issues.

I was recently diagnosed with Adult Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) at 28. Pretty much I had been living my whole life with a condition and had attributed so many negative words and beliefs to it. It explains though that while you wouldn’t see me pacing up and down walls and constantly needing to move, you would find that I would be playing online games due to not having the focus to stay on longer tasks (distracted,) generally being called a nobody (hard to talk with and to,) and having pretty poor social skills (not knowing what others interests were, overreacting.)

I would, and still have bouts, of being hyperfocused at either mundane or important tasks, as long as I start. Otherwise, that urge to do something generally leads to something that is simple, repeatable, and most importantly, dopamine increasing (spending money, exercising, cleaning the room etc.) because real life can just be a mental overload.

I relate to Cam in that most of the games I played were of the online type, where goals were easy to substantiate, where social activity was easy to get into, where I could check things off one-by-one. Because of that nature, that concept of “one more turn” became “one more level,” “one more mob,” “one more craft” etc. Out of all the friends I’ve made playing games online, only a few are people I have met in real life, and I tend to float in and out of social groups.

As in the article, people who are classed as ‘escapists’ and ‘procrastinators’ will find things to do that temporarily gives them a boost and a degree of satisfaction. Alcohol, gambling, games, exercising – anything that is repeatable and is not related to what the person’s “real goal” or “commitment” is can inherently be deemed “addictive” when it is a label that society has placed on them.

If you want to go further, consider that in many countries, cultural beliefs place the onus of being successful on the individual. As @transientmind points out, that is deeply seated in what society has as a whole projected upon those around them. And just because one person is able to go from being poor to being rich, media influences those who are poor to “get out there and do something.” People see those who are “lazy,” “clever but just don’t effort into it” as outcasts, and the vast majority of people who hear this think to themselves that is the case, further falling into a bottomless pit.

I won’t say I’ve heard all of these words, and I won’t say that game ‘addiction’ is not real – what I do want to say is that support is needed for people like Cam, and those interviewed, and for those who are out there who just can’t seem to stop. And while it should be up to governments and leaders, if society as a whole can change, then perhaps this ‘addiction’ could be turned into something beautiful.

Anything can be addictive. It comes down to the person, it’s no coincidence that the majority of those suffering from addictions also have other mental health issues. Or even just a predilection toward addiction. It’s completely right to not single out gaming, and treat it the same as any other addiction, because that’s all it is. You can’t blame gaming for simply existing. And honestly as far as addictions go, it’s far less damaging than alcoholism, which is thousands of times more prevalent.