The influx of randomised loot boxes has kicked off a permanent discussion about their inclusion in games. Discussions of multiplayer imbalance and blocked off game content ignore an important truth: loot boxes are an ethical problem. They exist largely to exploit players and create addicts.

Loot boxes in video games are digital goods that allow players the chance to obtain special items. It’s a bit like opening a mystery box. You might get something really cool or you might get a ton of garbage. They made inroads in gaming in Japan, where games with random loot mechanics earned the label “gacha”, referring to “gachapon” toy vending machines. Gacha became a cornerstone of mobile game design and now seems to be popular everywhere.

Gacha systems, chief among them loot boxes, are now a ubiquitous mechanic of mobile games around the world, and they have spread in recent years to AAA titles such as Overwatch or League of Legends. In many of these games, loot boxes can be earned by playing the game or purchased with special currencies gained through completing tasks, but they are also often available for purchase with real world money.

That last method is how many game makers hope their customers will obtain loot boxes. The boxes are a temptation and a snare. They are a devious economic trap, designed to take players’ money. You’re not expected to resist them forever.

In 1930, during his graduate year in college, American psychologist B.F. Skinner conducted experiments on behavioural conditioning in animals. He created a chamber where rats received food if they pushed a button. As a result of these tests, he determined two important things. The first is that the rats were more likely to do something if they were rewarded. They were more likely to push a button for food than push that same button to stop getting shocked by an electrified cage floor.

Second, he discovered that he could train the rats to push a button more if their reward was at either random or controlled intervals instead of offering a consistent reward every time.

Loot boxes are similarly designed to encourage real life sales by providing rewards that are rare and yet seemingly always attainable if frequently tantalizingly out of reach.

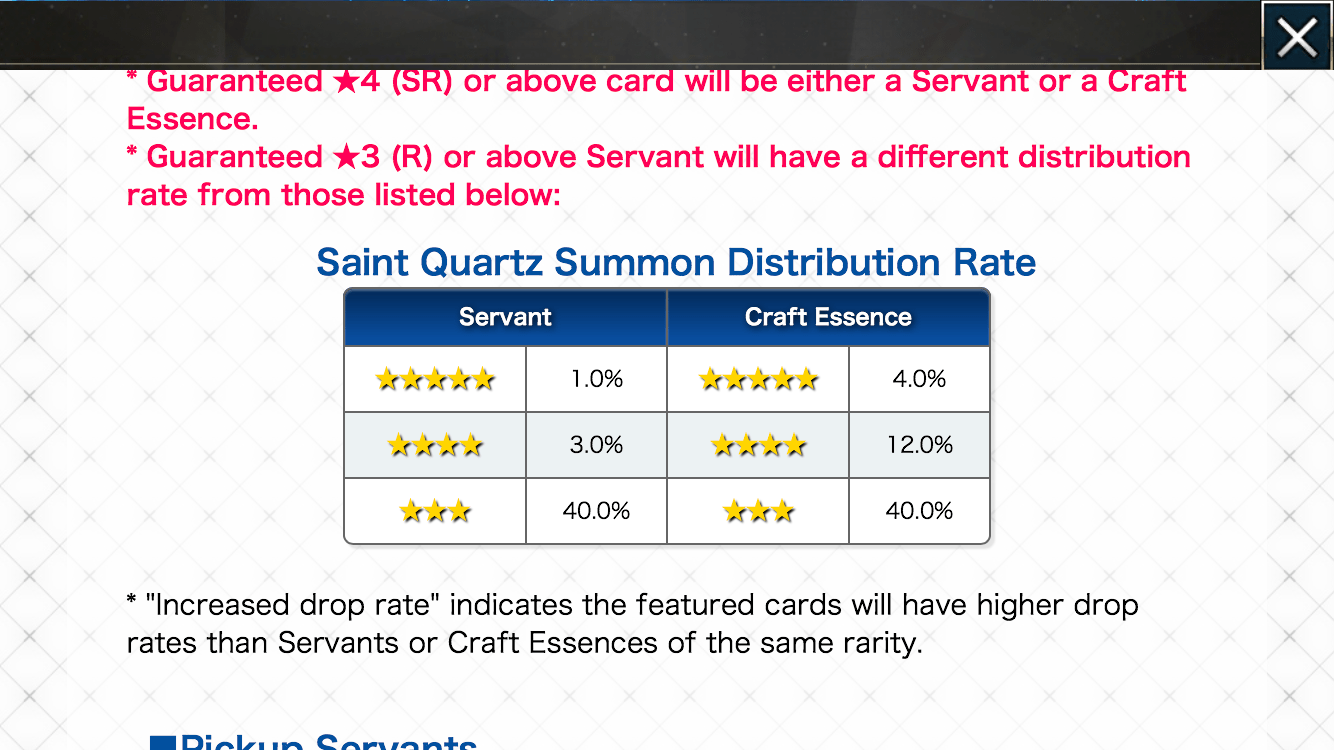

The rarity is usually implied rather than articulated. Most games don’t tell you the odds governing their lootboxes, though some do. The mobile game Fire Emblem: Heroes discloses probability of summoning new characters of varying quality within the game itself, a result of Japanese laws that mandate the practice overseas. For any given summon in Heroes, there is a three per cent chance of giving players a five star character, although that number starts to increase after multiple summons.

Overwatch crates are designed so that players will receive a legendary quality item after opening an average of 13.5 crates, according to numbers disclosed as part of Chinese regulations. These numbers may vary in different countries. The goal is to hand out loot frequently enough that players always believe they’re on the verge of getting good loot while also keeping probability low enough to encourage the purchase of additional crates.

Games with loot boxes also usually signal that you are always on your way to another possible reward, simply by offering loot boxes as rewards for play. Play enough Overwatch to level up and you’ll get a crate. This is a managed reward schedule meant to offer players a chance of accessing loot crates without buying them.

Given the chance to always get crates if they put in enough time and effort and given the chance to get a reward, players are then also teased with the opportunity to overcome the maths against them and just buy a loot box at will, should they have the cash (or, more to the point and more dangerously, the credit). Purchasing crates allows players to speed up this schedule. This design also applies to in-game currencies. Loot boxes and in-game currencies are designed to control when you receive rewards and offer alluring shortcuts to your next legendary skin or weapon.

On top of this, loot systems are designed to maximise use through carefully crafted audio and visual design. In interviews with my colleague Cecilia D’Anastasio earlier this year, the designers from games like Overwatch and Duelyst explain how their crates are designed to be a pleasurable experience.

“When you start opening a loot box, we want to build anticipation,” an Overwatch developer said. “We do this in a lot of ways — animations, camera work, spinning plates, and sounds. We even build a little anticipation with the glow that emits from a loot box’s cracks before you open it.”

Moment for moment, loot boxes are engineered to capture attention with a mixture of spectacle and psychological trickery not unlike what you might find at a slot machine.

If only to make one additional point about loot boxes and gacha, here’s why my phone was buzzing a moment ago. pic.twitter.com/ondl6slVaX

— Harper Jay (@transgamerthink) October 12, 2017

If this sounds shitty, that’s because it is. The ESRB recently told us that it doesn’t see loot boxes as gambling because players “always guaranteed to receive in-game content.” I find this assessment absurd. Games offer wide rosters of characters and run limited time events to create rarity that drives purchases.

Just because you get something, doesn’t mean you aren’t taking a gamble. I believe the ESRB is making an academic distinction to avoid acknowledging the issue and am sceptical of their assessment given that they were created by the Entertainment Software Association, a trade association dedicated to the business interests of game publishers.

The argument surrounding Shadow of War and Battlefront II has largely focused on the fact that their loot boxes affect gameplay. For instance, the boxes in Battlefront II have drawn criticism because they are the only means of gaining “star cards”, equippable boosters that affect player stats and weaponry.

In a statement yesterday, EA clarified that the best items in the game would not be tied to loot boxes. Still, the idea that players might “pay to win” and upset the game’s balance struck a nerve. Loot boxes for cosmetics were fine but boxes that affected gameplay were a bridge too far. This is as arbitrary as the ESRB’s position.

Whether they dole out cosmetics or gameplay-affecting items, loot boxes of any sort exist for the purpose of exploiting players. Whether it’s offering the chance to get Symmetra’s new skin or get a better rifle in Battlefront II, the only reason the loot box exists is to prey on the economically vulnerable. You are not a valued player; you are a statistic on a spreadsheet. You are red or black ink. Loot boxes certainly aren’t there for fun. They have always been designed for the purpose of making sure that a company turns a profit.

To some, loot boxes may be a gameplay issue or a consumerist concern. To me, they’re far more seriously a moral issue. I know, because I have fallen for them. I don’t know how else to say this, but I have a gambling problem. I didn’t find this out at a casino. I found this out playing games.

It started with the 2014 mobile game Final Fantasy Record Keeper. It was the first gachapon game I played, and I loved it. I was working as a barista at the time and it was a great way to pass time. The game offers bite-sized RPG battles waged by characters who could be equipped with armour and weapons that granted special abilities. That gear came from a loot draw that required in-game currency.

The game gives currency called mythril for clearing battles and for logging in. Get enough mythril and you “draw” for new gear without spending a dime. But as new in-game events offered iconic weapons and armour for a limited time, I gave in and spent money to try and get them. When a powerful new weapon was released for Final Fantasy VII‘s Cloud, I bought a heap of in-game currency and spent it until probability favoured me and I got it. As new weapons and armour were released, I began to do this more often. Sometimes it was because I liked that character, other times it was because the item was powerful and important to the meta-game.

I don’t care to estimate how much I spent on Record Keeper but I will admit that it got to the point that I was actually spending cash on iTunes cards so that the payments wouldn’t show in my credit card history.

Final Fantasy Record Keeper runs an animation when you draw for new items that is a thing of beauty. I mean that. It is made to be beautiful. It is a meticulously-crafted display of magical orbs, bouncy string music, classic Final Fantasy sounds, and moogles. It’s awesome, and whenever I think of it, I get sick.

Eventually, I backed away from Record Keeper. I don’t play it as much, but other gacha games still draw me in. I play a lot of Fire Emblem Heroes and Fate: Grand Order. These games allow you to spend in game currency on heroes for your roster. The best are often in limited time events. Some are incredibly rare; the chance for a five star hero in Fate:GO rests at around one per cent. I have three, and I have no clue how much money I lost in the process.

I’m actually pretty lucky. I play these games enough to grind out currencies to summon for free. I’ve actually gotten some great stuff on free summons from my gacha games. But even in that minority, I have plenty that were the result of spending my own money. Here’s the really fucked up thing: while I can arguably afford this addiction (and, really, I can’t) plenty of people who have started up with loot boxes or gacha games can’t afford it at all. They know it, but I promise you plenty of them are logging into Overwatch right now to get those Halloween skins.

When you go to a casino, they give you chips. When I log into Fire Emblem Heroes, they give me orbs. This isn’t a problem that started with Shadow of Mordor. It is something that has been a cornerstone of games for years now. Pull that lever and you’ll realise that these boxes are designed to fuck you over and take your cash. For every person who can step away, plenty of people can’t. It’s a system that preys on addiction, built upon mountains of research on how best to trick people into letting companies rob them.

I still play my gacha games. I still play Overwatch. I write about those games here. I think they’re fun. But we need to acknowledge what loot boxes are. They’re slot machines in everything but name, meticulously crafted to encourage player spending and keep them on the hook.

The problem isn’t just that games cost more to make or that loot boxes might affect multiplayer balance. The problem is that I can’t delete these games. The problem is that I’m not the only one. And that’s exactly what publishers are counting on.

Leave a Reply