When I think back on the games I played growing up, the Ultima series stands out as one of the most unique and compelling. These open-world fantasy RPGs helped define and establish many of the standards of the genre through nine main instalments and multiple spin-offs on a variety of platforms.

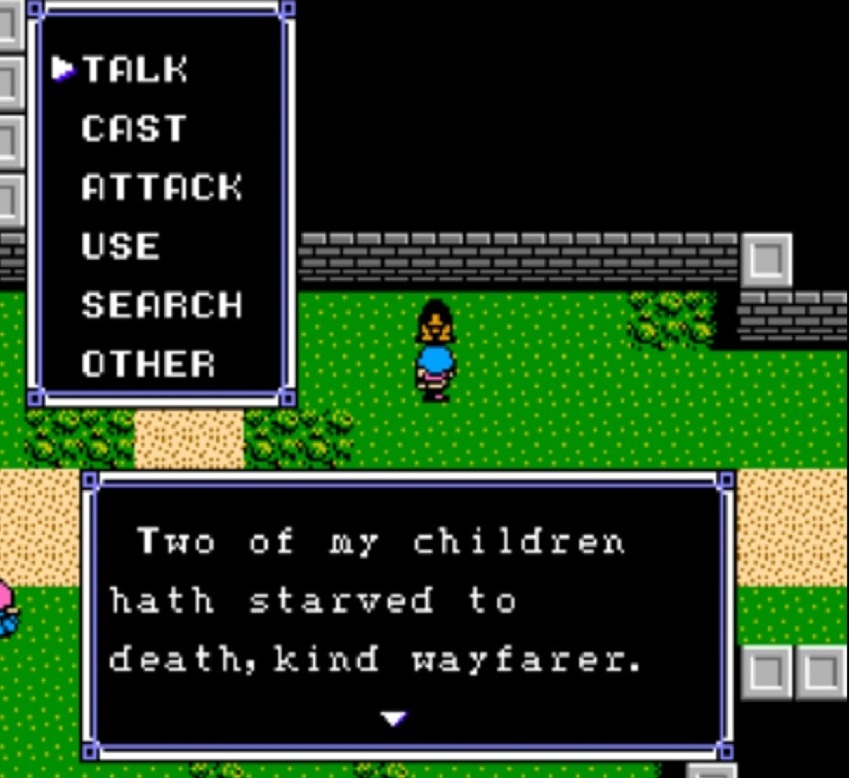

My first Ultima game was the third in the series, the Nintendo Entertainment System port of Exodus released in 1989, six years after the game’s initial release on Apple II. It was a difficult, but enjoyable, experience. But 1985's Ultima IV, which I played on the Nintendo as well, was the game that I fell in love with, because it went so much against the grain of a traditional RPG.

There weren’t villains you had to vanquish or an evil that had to be defeated. Your main goal was to be a good person and go throughout Britannia helping people. 1988's Ultima V flipped morality on its head by pushing the virtues of the avatar into a moral absolutism that was terrifying.

Further games in the series would push the boundaries of ethics, forcing players to question the binary values they’d normally associate with simpler gaming narratives.

Recently, I had the chance to talk via email with Richard Garriott, aka Lord British, creator of the Ultima series, about the games as well as the spiritual successor to the series Shroud of the Avatar to know more about the stories behind their development.

Grand Theft Ultima

For a lot of people, Ultima IV was the game that changed their whole perspective on the narrative possibilities of gaming. The ultimate goal of pursuing the eight virtues and becoming the avatar was so much more fascinating than the trope of fighting back some evil or saving a princess.

I asked Garriott about the evolution of the game.

“My previous games sold well, but Akalabeth, Ultima I and Ultima II were sold through other companies,” he said. “Ultima III was the first title published by my own company, Origin. This was important, because it meant that for the first time, when someone wrote to the company about the game, the letter came to me.”

The letters would reveal a disturbing trend. “I was very surprised to see the consistent pattern of the letters people would write about their experiences with my games,” Garriott said. “Generally, they would first state how much they enjoyed the games to date, but then there would be pages and pages of critiques.”

Garriott hoped that players, faced with the game’s open-ended moral choices, would choose to be good. But all those letters said otherwise.

“Players loved to kill all the NPCs in all the towns and steal from all the shops, and especially to kill my character Lord British in order to level up as fast as possible to become powerful enough to kill the main bad guys in the games,” Garriott said.

“That was not being very virtuous. I realised that in all three Ultimas, I had created games in which the best way to min-max the game was to be un-virtuous. Everyone was doing that in order to win as fast as possible. I was not going to allow that ever again!”

For Ultima IV, Garriott set out to make a game that would tempt players to take moral shortcuts. On the surface, the game would appear to allow such behaviour.

At the same time, there would be repercussions showing the appropriate side effects of these actions. “I set out to explore the best real moral codes I could find and began a long and deep era of personal research in philosophy and game design that manifested in Ultima IV,” he said, “its Virtues, its conversation systems, the term Avatar, the Virtues, and numerous other tropes that are now standards of gaming.”

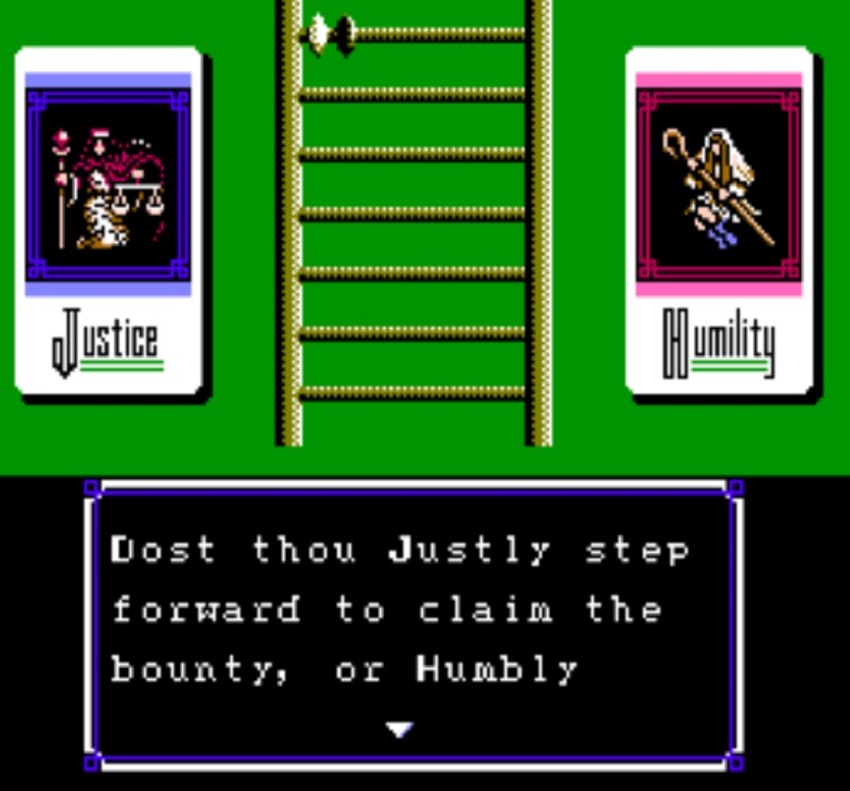

The game’s theme of pursuing virtues appealed to many players, and this sense of differentiating itself expanded to every element of the game, including the character creation. In the opening, rather than setting classes and stats, players are shown the Cards of Virtue.

They’re then asked a series of questions, almost like a psychological test, and the preferences determine the character they start with.

“The cards came about as a tangential way to build a character model of your ethical preferences through practical comparisons,” Garriott explained. “It came about through a psychological test I heard about from one of my brothers who is a doctor.”

The test, Garriott said, went like this: “Imagine Popeye and Olive are in love, yet live across a raging river from each other, so they cannot reach each other. Olive goes to Brutus, who has a boat, and asks him to take her across. He says he will, if she sleeps with him first.

She says no. She asks the only other person with a boat, Wimpy, who says he won’t help as he does not want to get involved. Distraught, Olive submits to Brutus’ demands and gets across the river. Olive confesses what she has done to Popeye, who now spurns her.

Olive cries to Sweetpea, who goes and beats up Popeye and calls him an idiot.”

“The psychological test was to rank in order who did the worst things in this story, and discuss. I found this test interesting in that people’s reaction was often not what you would expect and the bias was often not what or by whom you would expect.

I spent months crafting virtue questions that wouldn’t bias answers to favour any of the 8 virtues I had created. Some questions were far far reaches, but most were sincere and difficult choices. In the end, I think we came away with a pretty good profile of the player’s true ethical bias!”

“Thy Lord mistakenly believes he slew a dragon. Thou hast proof that thy lance felled the beast. When asked, dost thou: A) Honestly claim the kill and the prize? B) Humbly permit thy Lord his belief?”

Few game series have pulled off such a shift in focus, from defeating monsters, like Exodus, to conducting oneself in a moral and ethical manner. I loved how each of the virtues was interpreted in Ultima IV, from giving alms to the poor, to letting natural creatures escape from battle.

As Garriott pointed out: “If you fled from a weaker evil that would then prey on some other villager, that was cowardice. But there was no ill will to let a hungry bear live to go hunt rabbits instead of you.”

What’s fascinating, and troubling thematically, about Ultima V was that everything good in IV becomes corrupted through the antagonist Lord Blackthorn’s scary absolutism. Blackthorne’s Code of Virtue has draconian laws: “Thou shalt help those in need, or thou shalt suffer the same need.”

“Thou shalt donate half of thy income to charity, or thou shalt have no income.” “Thou shalt not lie, or thou shalt lose thy tongue.” There’s many lessons that seem all too familiar today with politicians espousing religious texts to justify what seems obviously inhumane.

“Ultima V was a poke at what I had just created with Ultima IV,” Garriott stated. “It was a time when the ‘Moral Majority,’ who condemned video games regularly and called people like me ‘the devil,’ were constantly claiming to be faith healers and bilking people for money, while being caught with mistresses and begging for forgiveness.

I was so incensed with outrage by the hypocrisy created when a supposedly good philosophy is hijacked for personal gain or overrun by extremists and dogma. I have and continue to find that headlines, and especially things that give me a sense of moral outrage happening in the world around me, are the best sources of plot ideas for the games I work on.”

Ultima V has many great plot moments and some shocking ones as well. Lord Blackthorn’s arc, from trusted friend to the prime villain and then penitent exile, was a moving one. He also executed one of your party members, a sequence that was traumatising for me when I first played it.

“One of the main goals of the second trilogy of Ultimas was to craft worthy villains,” Garriott said of Blackthorne. “To that end they needed to have agency in the world.”

Most game villains, he said, just “wait in the final level for you to come kill them,” sitting patiently on their thrones while you min-max and level up by killing NPCs. “I wanted my new villains to be worthy of your hatred!”

“Thus, starting as a friend was good, killing a party member, even better. But in the end, I also wanted to show that I really do believe that redemption is possible for pretty much everyone. Not that punishment shouldn’t fit the crime.

But, in a game, I wanted to be a bit ‘lighter,’ in the end,” he said.

Gargoyle Ethics

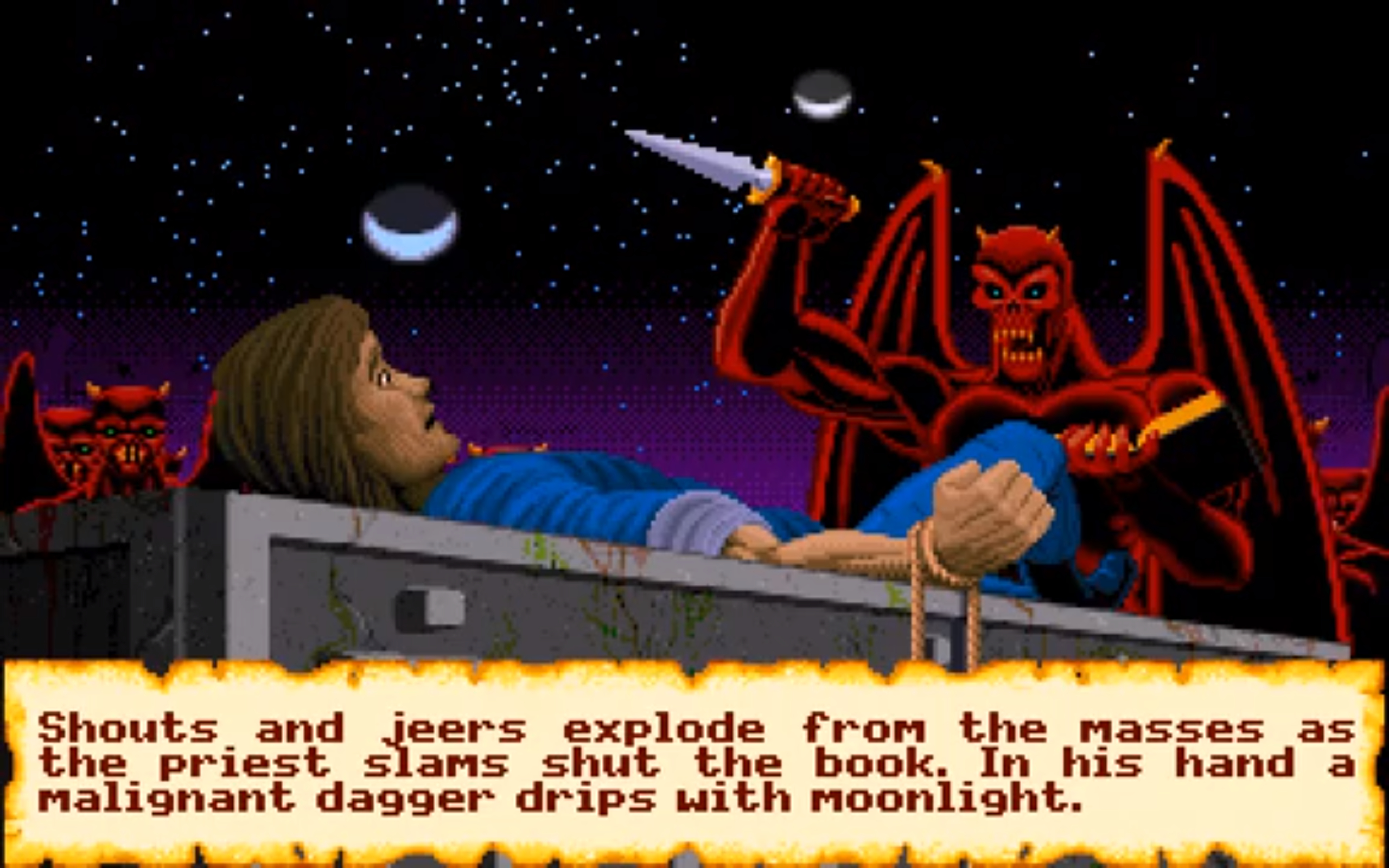

1990's Ultima VI: The False Prophet turned everything on its head again with the arrival of the seemingly devilish Gargoyles. Their nefarious intent seems all the more apparent when they try to sacrifice the Avatar on an altar. Fortunately, he’s rescued by his companions. But, being an Ultima game, there’s much more to the situation than meets the eye. Deep commentary ensues in the game on ethics, race, and morality, especially when you see the events of the world from the Gargoyles’ perspective.

“Sadly, I think Ultima VI is a game that needs to come back out again right about now,” Garriott said. “Just as today, it was a time when affirmative action, and border issues and overseas… issues seemed to be at a peak. Oh, how history seems to repeat itself.”

“What I tried to show was that racism is learned and any of us, myself included, could be, likely have been, maybe still are, harboring some levels of bias or outright racism still within us. We all carry assumptions about things around us about what and how we perceive the world.”

The war with the gargoyles upends expectations and biases, especially as the gargoyles have their own sets of virtues that differ from the Avatar. Players learn that the Avatar’s past act of taking the Codex of Infinite Wisdom ruined the gargoyle world, resulting in catastrophic destruction. In their eyes, it’s the Avatar who is the villain.

“Far too many perpetual conflicts in the world are sustained generation after generation due to these deeply held beliefs and grudges that prevent any real progress from being made,” Garriott said. “Honestly I don’t know how we are going to solve this in the real world, but I think it’s important to play out in a fictional world, so we think about it.”

Evolution of the Avatar

One of the most interesting aspects about Ultima is how much the moongates and planetary orbits play an important role. His father, Owen Garriott, was a NASA astronaut, and Richard Garriott himself flew aboard the International Space Station in 2008 as a private astronaut. I asked him about the role of space and stars for the series.

“Since reading The Hobbit as my first bit of fantasy and being so astonished that the runes on the map could really be read ‘stand by the grey stone…’,” Garriott said, “I became a ‘Tolkien style’ reality crafter, desiring to create deep backstories and deep reality mechanics behind the worlds I crafted.”

“The Ancients on earth realised that seasonal weather was predicted by the movements of the stars and sun and tides by the moon. So it’s forgivable they would speculate about much more. I find it compelling to deliver on the truth of that speculation. We need systems to drive the spawns and movements of various system anyway, so why not expose them to the hardcore players who are willing to become the shamen of the new world, those willing to read the runes and study the stars!”

Just as the stars are in flux, Garriott has moved on from the Ultima series to work on several other games. The latest, Shroud of the Avatar: Forsaken Virtues, is considered a spiritual successor to the original series.

I asked Garriott about Shroud, and what he learned from Ultima in approaching the new game.

Garriott said that when he begins a new game, he usually asks himself two questions: “What is the compelling moral outrage happening in the world these days?” and “What is the technical area we hope to advance this game?”

In answer to the first question, for Shroud of the Avatar, Garriott says: “Sadly we seem to have gone backwards in my book and tolerance and racism are back on the front burner again.” As for the second: “For SotA we are creating a “selective multiplayer,” where the game can throttle from solo to MMO-like states, for storytelling and even offline play.”

“Each new game faces new challenges. We toss out failed experiments of the past. Learn from great innovations of our competitors. Plus, of course there is new hardware to master,” he said. I asked about some of those failed experiments. “Oh, so many failed experiments,” he said.

Our most famous failed experiment was the virtual ecology attempt in Ultima Online. We had a beautiful plan. Grass would spawn vegetable mass. Herbivores would come and eat it, they would come to steady state. We would spawn carnivores, they would come to steady state with the herbivores and vegetable growth. The team built beautiful code. It worked beautifully. It was a masterpiece! That was until, we invited in the players.”

“As soon as players arrived, they killed all of the herbivores and all of the carnivores as fast as we could spawn them,” he said. “It didn’t matter how fast we turned up the spawners, nothing existed unadulterated long enough for the system to play out in any way shape or form. Eventually the system was full ripped out of the game. No one ever even noticed the beautiful attempt at virtual ecology.”

“SotA has made far fewer big failed systems,” he said. Since the game is updated each month, players can weigh in with their thoughts, and Garriott’s team can course-correct immediately.

“That’s not to say everyone loves everything about SotA, but we don’t have big systems we have or plan to pull,” he said. “We make constant slow refinements as we go.”

The Quest Of The Avatar Is Forever

A lot has changed since the first Ultima released in 1981 for the Apple II. But the message and themes of the series seem just as relevant as ever, especially with so much change happening politically and historically.

It seems our world could use a new band of heroes and avatars. Light-heartedly, I asked Garriott what his in-game character Lord British would say to the people of Earth in 2018.

“Democracy in the real world is under siege,” wrote Garriott-as-British. “It has been in the past. But, we fought devastating world wars to fix it in the past. Today we have a lot more nukes and a lot more 1984-style mass control systems than we did back then.”

“It might be a lot harder to fix now, if we let it get out of control. I believe we are at a very real and very important inflection point in history. I really hope that the European Union survives. I really hope that the independent democratic institutions of the United States survive.”

“But, sadly, I think there is a real risk that we are going to see an era of global ‘strongman’ leaders who manage to concentrate power by making literal ‘rubber stamp or get rubbed out’ out of their other branches of governments, control their military and police to become enforcers against their populace and press. While I would like to think it could not happen in the USA, personally, I think it is already happening in the USA. In other countries, former enemies which we have suddenly become great friends with, these tactics are already very well evolved. Don’t think it can’t happen here. Because it is. Stay vigilant Avatars!”

Comments

9 responses to “The Story Behind Ultima’s Morality”

Art imitates real life once again…

Yeah, ones one of the more popular stories from Ultima Online. The entire ecosystem just fell apart as soon as people started using it.

What most of the stories don’t really get across though is what happened once the (now abused) ecosystem had run its course. Players had no challenging content to play, so did the only thing they could. They turned on each other.

The entire situation is a great case study on human behaviour, and was a wonderful reference source for future MMO’s that focussed on PvP.

Personally, I hated it. The griefing drove me from the game. But I had to respect how efficient a PvP system it turned out to be.

Great article! I wasn’t able to play the old Ultima games but enjoyed the later ones.

The earlier games are wonderful examples of what could be done with minimal resources. that was back in the day when memory as counted in kilobytes, not terrabytes, and storage was only on 5 1/4 floppies. Hard drives were years away.

The depth in 4, 5, and 6 were years ahead of their time. Theres good reason they’re referred to so fondly.

I first came across the Ultima games with Ultima 2, but Ultima 4 was always the highpoint for me.

I came in at 3 which was incomprehensible at my age at the time, but I fell in love with 5 when it came out at the tender age of 10. Needless to say I completely missed the point and had an Avatar named Conan who slaughtered and robbed his way across Britannia.

When the two trilogy sets came out I had a better idea and played them properly. Loved them greatly.

Unfortunately I replayed them recently with the whole Shroud thing going on and found I don’t enjoy them anymore. (And 8 is the worst)

Shroud I was into until the whole thing got hijacked by the pvpers demanding to be able to mutilate other players and craft things from the body parts. I patch and load the game every couple of months to keep my property, but the performance of the game on my PC is terrible.

Spoony’s videos did a great job on the Ultima series.

Anyone ask him about Ultima 8 & 9, which seemed designed to shit all over the past 7 chapters?

Pretty sure he would say “I still can’t believe you fuckers assassinated me in Ultima Online. You deserve everything that’s happening to you!”

I only ever played ultima 8.

I found it very tricky!

After reading this article, i dont recall the game being morality driven. I was only maybe 10 or 12 at the time though